|

Whetting your palette

|

|

December 17, 1999: 7:18 a.m. ET

Fancy a taste of the art world? Investing and collecting can go together

By Staff Writer Alex Frew McMillan

|

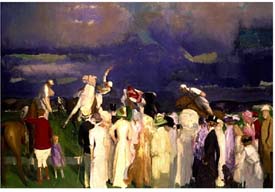

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - When George Bellows’ Polo Ground fetched $27.5 million at Sotheby’s in New York on Dec. 1, it set a record for an American painting.

But that’s hardly a surprise. In the art world, record highs are commonplace these days -- not unlike the stock markets that are helping to pay for the boom.

Two Van Goghs, a Cezanne, a Winslow Homer, and several Surrealist pieces have all been snapped up for multimillion-dollar prices in December alone. The art market for many mediums, periods, schools and styles is riding high.

"We’ve got huge prices being secured in the past year,” said C. Hugh Hildesley, executive vice president at the auction house Sotheby’s.

Unlike previous peaks, he thinks this one can be sustained. "It’s a very, very strong market. But much more discerning -- the people who are collecting are collecting with great knowledge.”

The beneficiaries of newfound wealth from the stock market in the second half of this decade may be tempted to invest paper gains in something more tangible. But how realistic is it to think you can "invest” in art?

It’s not about money, exactly

It’s tempting, particularly for people looking for a pastime that pays off. The process can be very rewarding, both figuratively and literally, experts say. Entering the art world is also tricky and intimidating. It takes time, interest and effort, not unlike conventional investing. But unlike the stock market, the art world isn’t mainly, or at least brazenly, about money.

"Frankly people who have ‘made money’ in art are people who didn’t buy art to invest. They bought it because they knew it and they understood it and they loved it,” said Gilbert Edelson, a vice president with the Art Dealers Association of America.

Sure, sure. But cash comes into it in the end. "It doesn’t hurt to make money on it,” Edelson admitted.

The art world and money have a funny, symbiotic relationship. It’s with money, not about money, most industry insiders seem to say. "Nobody likes to be found to have made a bad investment. But you also don’t want to seem crassly mercantile about it,” Hildesley said.

On Dec. 1, Polo Crowd by George Bellows sold for $27.5 million, a record for an American painting.

Click here to see a larger version of the painting.

Art can make a good hedge for an investor with a lot of stock assets, dealers point out. Though you’re more likely to get better returns in the stock market, the appreciation can be remarkable on the right piece.

Even something as simple as a chair can reap substantial rewards. For instance, a Chippendale that set a record for an American side chair at $275,000 in 1983 reset the record at Christie’s in October when it went for $1.4 million. That’s a gain of 421 percent in 16 years, or 26 percent a year. No Internet stock, true, but still nothing to scoff at.

The corresponding horror stories are harder to hear, but the art world does boom and then bust, often in conjunction with the economy. The last two major art booms, in the late ‘70s and the mid to late ‘80s, were both followed by recessions that saw big dips in art prices.

It’s not as simple as saying that a painting appreciates when GDP goes up. The ‘70s art boom came at a time when stock investments were performing poorly and collectors started looking for both a hedge and good returns in art. The ‘80s saw strong interest from speculators. Large sums of money also flowed into the art world from outside the United States, particularly Japan.

When they say 'buy and hold,' they mean it

The current art boom seems less speculative and more controlled than previous hot streaks, art world workers say. Even the buzz in the auction rooms, a fervid scene in the ‘80s, is more subdued. Buyers seem better informed, partly thanks to the spread of information and educational material via the Internet, art insiders say.

"Good things are bringing strong, huge, record prices,” said John Hays, a senior vice president at the auction house Christie’s. "But they’re being bought by collectors who hang on to things. This is a very sanguine market.”

There are probably only a few thousand "serious” art collectors, though it’s impossible to track exact numbers. For most collectors, their stake in art is "mad money,” maybe 10 percent to 20 percent of their overall portfolio, said Hays, who runs the American furniture sales department. But some very dedicated collectors are willing to put 50 percent, even as much as 70 percent of their assets into their collection.

Those collectors have to be very sure of themselves and their long-term financial position. One main concern for art buyers is that the market is very illiquid. Never spend money that you may need for at least 10 years, Hays suggests. It’s a drawn-out process to sell art at the best of times.

At the worst, you can be forced to sell at a considerable loss in a downturn. If you’re able to hold a piece long term, you can wait for times turn good again, should this boom not prove as long-legged as the experts claim it looks to be.

There are also commissions to pay -- anywhere from 6 percent to 10 percent at an auction house and 10 percent to 20 percent through a dealer, though that’s negotiable. Catalog, transparency and insurance costs also add up and make frequent selling unattractive.

It’s important to hold long-term for another reason. The price of a piece will drop if the small circle of collectors and dealers interested sees that it comes up for sale too frequently, experts say. Hays compared art collecting to dating. "The new boy or girl is always a little more interesting,” he said.

Hildesley at Sotheby’s agrees. "If something comes back 15 to 20 years later, that’s fine. But if it comes back five years later, people tend to wonder why.” The collector John Whitney bought the Polo Crowd in 1929, for instance. A painting like it had not come on the market for a long time, partly explaining the high price.

Tips to get a novice collector started

Hildesley has some other suggestions for people who are looking to break into the art world.

Rule No. 1 Pin down your area of expertise. Find something you are personally interested in. "You can’t just follow trends,” Hildesley said.

Rule No. 2 Do your homework. Read around the subject and time period that captures your fancy. Visit the museums with collections in that field. If possible, consult the experts who study it. Not only will they provide valuable criticism on the artists, but also they’re likely to be the ones who assess the authenticity of disputed works.

Rule No. 3 Get to know the market. There are likely only a handful of serious dealers -- probably a half dozen at the top, Hildesley said -- in any period or specialty. Contact them in person if possible, and get on their mailing lists.

Rule No. 4 Attend the auctions in your field. Many are annual events. Go to a lot of auctions and make sure you feel comfortable you know what you’re doing before you ever consider bidding, Hildesley suggests.

Rule No. 5 Carve out a strategy for what you are trying to achieve in your collection. Novice collectors should consider paying a dealer to act as their agent once they feel ready to buy, he said. They can introduce a prospective collector to what’s typically a tight-knit world.

"By the time you’ve spent 50 years studying carefully, you know a bit,” Hildesley joked. "It’s not a flash-in-the-pan thing.”

Most speculators who lost money, particularly by buying in the ‘80s, lost because they didn’t know enough to buy good pieces. "A little learning is a dangerous thing,” Hildesley said.

Cezanne’s Bouilloire et fruits sold Dec. 7 in London for $29.3 million, double its estimated value.

Click here for a larger version of the painting.

Louis Salerno, a dealer whose Manhattan gallery Questroyal Fine Art specializes in 19th and early 20th Century American paintings, says he knows several people who are "extremely successful” at trading art for profit more than pleasure.

Some of them are collectors who dabble as dealers. Some of them are wealthy professionals who get a kick out of putting their business savvy to use in the world of aesthetics.

Whatever the motivation, he says turning art buying into an investment can be done. That’s even though almost all experts warn speculators off investing in art to make money.

"I know that’s the conventional response,” he admitted. "But I would say that with an adviser that is both knowledgeable and trustworthy, and if you’re willing to gain a good understanding and educate your mind as well as your eye ... and you have X amount of capital you can put at risk, because it is risky, then I think there are good opportunities. And I think it’s certainly worthy to be considered an investment.”

In general, the older the work, the less risk involved. But there’s a catch. Established works are cost prohibitive for most people. Though the Impressionists grab the headlines with big prices, many works are more affordable -- particularly photography -- when it comes to visual arts.

Overall, both Christie’s and Sotheby’s say the majority of their lots sell for less than $10,000. Sotheby’s also sells more-affordable pieces, particularly collectibles and memorabilia, through a site it launched last month with Amazon.com. Christie’s also plans a site.

The more modern and the lower the price, the greater the risk. "Go down to the galleries in Chelsea or SoHo [in New York] and 99.9 percent of what you see will decline in value,” Edelson said. "But if you’re lucky and smart enough to pick that one tenth of one percent of the artists that will increase in value, then you have a great eye and you’re a great collector.”

Salerno, whose field of American painting has seen a recent surge in popularity, says buying quality is the key, coupled with good timing. For instance, he bought several pictures by 19th Century U.S. painter Martin Johnson Heade over the last two years knowing that the Boston Museum of Fine Arts was organizing a Heade exhibition. The exhibit, which in February will move to the National Gallery of Art in Washington and then the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, has fueled renewed interest in the once-forgotten 19th Century painter.

His pieces have appreciated substantially in the short period he has owned them, gaining 50 percent to 60 percent and in some cases doubling in value, he said. But those are averages, and some less important works have underperformed. He thinks that reinforces the vagaries of the art market.

"That’s the thing -- I can have two Heades and you can have two Heades, and mine can be worth the same as they were two years ago and yours can triple. This is not something you can do without having a very reliable expert or doing your own due diligence.”

If you’re thinking about art as an investment, "you’re in a gray area to begin with,” he conceded. Only a person who is very well diversified and with a high net worth should really consider it, he said. And it doesn’t work out for everyone.

Whether you’re buying $20,000 or $2 million pieces, there’s a good chance you’ll see a significant appreciation if you buy the best quality you can find and afford, Salerno said. And if you make a mistake, you can always live with the consequences. "It’s always right if you enjoy the piece, and it gives you pleasure.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|