|

New exchange eyes options

|

|

January 11, 2000: 6:20 a.m. ET

New options exchange shooting for a March start, but how popular will it be?

By Staff Writer Alex Frew McMillan

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - In the summer of 1997, E*Trade founder Bill Porter and his partner, Marty Averbuch, walked into the office that David Krell and Gary Katz were sharing on Exchange Place in Manhattan's financial district. "We've heard about you guys," Porter said, "and we want to hire you."

Porter asked the men, both veterans of the New York Stock Exchange's options-trading operation, to answer two questions. Was there a niche for a new options exchange, an electronic options exchange? And if so, how do you do it?

Krell figured the E*Trade founder, now 71 and a former scientist, had happened on the wrong destination. "Dave told Porter he should go to Bellevue down the road here," Katz recalls, referring to New York's best-known mental hospital. After all, no one had taken on organizing a new exchange in the United States in the last quarter century.

But Porter wasn't on his way to a mental institution. By September that year, Krell and Katz had signed on. Now the two men, who left the Big Board when it sold its options-trading operation to the Chicago Board Options Exchange, find themselves bringing the fruits of Porter's imagination to life. They've melded his ideas with insights they gleaned logging thousands of frequent flier miles visiting options exchanges from Austria to Australia.

New exchange promising, but untested

The sounds of sawing and drilling rip through the air of the three floors their new company, the International Securities Exchange, will occupy. "We stumbled across this business," Krell, now the ISE's president and CEO, admits.

The hub of the ISE is its data center on the 27th floor at 60 Broad St. Eight battleship-gray cabinets, 5 feet high by 5 feet wide by 3 feet deep, house the whirring computers that will power the exchange. Gas extinguishers to starve any fire of oxygen protect them. The ISE also has a backup system across the Hudson River in Jersey City, N.J.

The ISE's founders (from left): Gary Katz, Bill Porter, Marty Averbuch and David Krell

The exchange will link to its clients via T-1 and T-3 connections, but the "floor" of the exchange itself is amazingly small -- those eight computer cabinets. The whole of the ISE fits on two floors, one for its executive operations and one for its data center and market regulation. Late last year it leased a third floor, which remains empty for expansion and a future training operation.

And the ISE has growth on its mind. It expects to corner 20 percent of the options market and still hopes to debut March 24 as the first floorless, electronic options exchange in the United States.

The ISE wants to debut then because that's the first Friday after the expiration of March options. So the exchange would have a "clean start," Katz explained, and a weekend for its employees to mull over the results of its first trading day.

But the ISE originally expected the Securities and Exchange Commission to approve its exchange-status filing in 1999, and the word has yet to come from the regulators.

"We're working on their application for exchange status," said SEC spokesman Chris Ullman. The commission knows the ISE wants to be up and running by March 24, he said. "We're definitely aware of that and moving as fast as we can."

Even if it doesn't hit its proposed start-up date, the ISE still expects approval early this year. So the company is hustling to make a home of the space it has leased, a few blocks away from that two-man cubbyhole Porter popped into in the heart of Wall Street.

The company has filled its world with frosted glass, flat-screen TVs and computers, computers, computers. The employees are mostly young men who dress down in plaid shirts and jeans and spend their lives staring at computer screens.

After a brief stint on Wall Street itself, 60 Broad St. is the ISE's third home. And Wall Street is watching as Krell and his colleagues prepare to launch their new exchange. "We think that the project is interesting, encouraging and well-intentioned," a Bank of America options trader wrote in an e-mail.

Those sentiments are common in the financial community, which seems to cautiously endorse the ISE while in the next sentence pointing out that it is as yet untested. Some mumble that many of the innovations it hopes to bring to options trading already have happened.

Bringing ECN technology to options trading

The ISE sells itself as a low-overhead, more-efficient alternative to the four existing options markets. Since its formation two years ago, the ISE has gone from two people to 69 full-time workers.

By promising to cut the cost of executing options trades by 30 percent to 50 percent, targets Krell says the ISE will in fact exceed, it has attracted significant Wall Street attention. It counts Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, Bear Stearns and Deutsche Bank among its 10 primary market makers.

The primary market makers, who will operate somewhat like specialists on the NYSE, together own 50 percent of the company and will each supervise trading in the options of 60 companies. The baskets will be split up by volume, volatility, industry and nationality of the underlying company, to try and ensure they're equally attractive.

The rest of the ISE, which is technically set up as a limited liability company for tax purposes, allowing investors to write off losses immediately, will be owned by 100 competitive market makers. They also will buy the right to trade 60-company baskets of shares but, unlike the primary market makers, will not be obligated to make two-sided markets in them all the time and ensure there is orderly trading.

The ISE will use similar computer technology and the same low-overhead strategy as electronic communications networks, or ECNs, that have revolutionized the execution of stock trades. The ISE has spent $5 million on Compaq computers alone.

But options, which have numerous "series" with different expiration dates and strike prices at which they can be converted, are more complicated vehicles to trade than stocks. "You can't just do this on a bunch of Dell PCs," Krell said, like ECNs. "We dwarf them in size and complexity."

Where an ECN may offer trading in a few thousand stocks, the ISE estimates it will offer trading in 60,000 options series. In other words, each basket of 60 companies will have 6,000 series, an average of 100 options series per underlying stock.

Options trading needed reform

When Porter came calling, the first of his questions was more or less rhetorical. Brokerages wanted to reduce their cost of executing options trades, which were not nearly as profitable as stock trades, even though brokerages charge more for an options contract than a stock trade.

The options world is a tight one. The Chicago Board Options Exchange handles just over half, 50.1 percent, of the 2 million options contracts -- each contract is for 100 shares -- that trade in the United States each day. The American Stock Exchange accounts for 25.5 percent of the volume, followed by the Pacific Exchange at 14.8 percent and the Philadelphia Stock Exchange at 9.6 percent.

Both the Securities and Exchange Commission and the U.S. Justice Department are investigating whether the existing options exchanges engaged in anticompetitive behavior. Prior to 1999, they had a "gentlemen's agreement" not to trade each other's most-popular options issues, though that broke down last summer. "Multiple listings" are now commonplace.

Because the options market is now fragmented, with options trading at different prices on different exchanges, the SEC has also ordered the options markets to link up their trading, setting a Jan. 19 deadline for them to come up with a plan. The executives of the ISE and the four existing exchanges will meet Jan. 12 to finalize it. At the moment, "crossed markets" can and do occur, where the bid on one market is above the ask on another, for example.

But the main push behind the ISE was to reduce the cost of trading options. Brokerages were paying much more to execute options trades than the floor traders at the exchanges, Krell said. In the face of such a split cost structure, and frustrated that options trades weren't nearly as profitable as stock trades, they came to Krell and Katz.

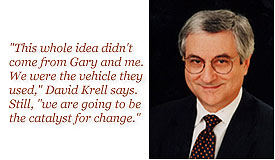

"This whole idea didn't come from Gary and me -- we were the vehicle they used," Krell says. The options-trading world had hardly changed in the last quarter century, he said, "and we said we are going to be the catalyst for change."

Porter and Averbuch had behind them a group of broker-dealer companies, including the retail online brokerages Ameritrade and E*Trade and the market makers Knight/Trimark Group and Herzog Heine Geduld, that put up the money to fund the ISE. Together they created Adirondack Trading Partners, which paid the ISE $61 million for the market-maker memberships, most of which it has now resold. That got the ISE, which has yet to earn a penny of revenue, off the ground.

The brokerages looked to Krell and Katz to give it momentum and run day-to-day operations. Though Porter is the ISE's chairman, he spends his time on the West Coast and hasn't moved into his New York office yet. He will be at the ISE only part-time when he does. Averbuch, 47, runs Adirondack Trading Partners out of an office in Centerport, Long Island.

CBOE's loss was ISE's gain

Krell got into the options-trading game with Merrill Lynch in 1978, then moved to the Chicago Board Options Exchange and, ultimately, fought a losing battle to keep the NYSE afloat in options trading.

The NYSE decided to get out of options trading in 1996, realizing it was losing market share. In April 1997, the CBOE bought the NYSE's dwindling options business, but it didn't take on any of the dozen staffers. Not that they wanted to go, according to Katz, now the ISE's head of marketing and business development. "The feeling was mutual," he says. The NYSE staffers "weren't interested in CBOE or in moving to Chicago."

During the fallout, Krell, now 53, took Katz, now 39, out for breakfast one morning. "What do you want to be when you grow up?" the older man asked the younger. The two decided to form their own consulting company, the short-lived K-Squared Research, to put their financial-services experience to work.

When Porter first visited K-Squared, Katz and Krell were working on an entirely different project that had nothing to do with options. They figured there was money to be made helping NYSE specialist firms market themselves better to their clients.

So K-Squared was developing ways to package data that specialist firms could give to the companies whose stock trading they supervise. The idea was that the specialists might want to sell themselves better to their clients to generate referrals when other companies in the same industry were looking to list on the Big Board.

But Porter wanted Krell and Katz for their options expertise. After his start at Merrill, Krell spent a while as the manager of CBOE's marketing and sales division, then moved to the NYSE's options-trading business, where he managed marketing and new products for 13 years.

Katz had started as an actuary with Equitable Life Assurance, then moved into research and business development at the NYSE in 1986. He also helped start the Options Industry Council, a trade group that promotes options trading.

The challenge for Krell and Katz was to meld the best features of an auction market, with its liquidity and orderly trading, with the low overhead and rapid electronic execution that computer technology offers. "When they heard we wanted to do it with technology, it was an easy sell," Krell recalls.

Though the online brokerages that backed Adirondack Trading Partners and the ISE were keen to provide their computer-programming expertise, Krell wasn't keen on that.

"We knew we would have had to teach them how to spell the word 'call'," he joked. Instead ISE turned to the Swedish OM Group, a technology-development company that started as an options exchange and now also owns the Stockholm Stock Exchange.

ISE hopes to cut costs, increase efficiency

Though there are electronic options exchanges in Europe, they are either "order by order" markets, which just execute trades as they match up, or dealer-driven markets, where a dealer, normally a bank, chooses to take one side of a trade.

But participation in both of those types of markets is voluntary, Krell said. The companies trading on them can stop trading at any time. "When the markets get frothy they can disappear," Krell said. "When the markets are frothy is exactly when consumers need them." The electronic options markets Krell and Katz studied were also much smaller in volume terms.

OM Group spent 60,000 man-hours adapting its electronic-options-trading technology to suit the ISE. To try and guarantee liquidity even when the market turns down, the primary market makers have to offer quotes on both sides of a trade at all times, though they're under no obligation to route their own options traffic to the exchange.

Krell says they will want to because the lack of a trading floor, and the correspondingly lower overhead, means the ISE will be a more efficient way of executing options trades. "I've always felt that, given the fact that we would be fully automated, we would be able to pass on the savings to our market makers," he says.

Much of the market maker's pricing can be computer modeled to shift when the price of the underlying stock changes. But the market maker's traders can also "finesse" their pricing if they so choose. Without having to have four traders in four cities on four separate trading floors, a brokerage can get by with fewer traders to oversee the same amount of options series, Katz and Krell maintain.

A broker who trades options from four to six companies on the floor of an exchange could well handle options from 10 companies through the ISE, they say.

The ISE's computerized trades will take less than half a second, compared with the 5 to 10 seconds and up to 5 minutes on a traditional exchange, Katz said. And the ISE's system also will allow the brokerages to trade anonymously, identified only by the class of trader they are rather than their name. That, the exchange hopes, will prove a very attractive feature if they have a large order to move. On the floor, of course, a brokerage's traders are immediately visible.

Before the threat of the ISE forced a change, Krell says, a brokerage typically used to pay 30 cents a contract to an exchange, as well as a fee to the floor broker to execute the trade. Though it hasn't established its fee structure yet, the ISE will cut out the floor brokers and reduce the cost of executing the trade as much as half, Krell said.

But questions about the ISE's role abound

In response to the threat of competition, though, the existing options markets already have cut their costs. In fact, the Philadelphia Stock Exchange on Jan. 3 started waiving its fee for trading up to 250 options contracts altogether, if the trade goes via its automated trading system. The CBOE points out that 35 percent of its trades are already routed through its electronic system.

"The CBOE has continued to upgrade its electronic systems and is fully prepared to compete with any current or new exchange," CBOE Vice President Ed Joyce said through a spokesman.

Faced with impending competition, the options exchanges also unfurled other changes, not least of them multiple listings. That has brought narrower spreads, sometimes cutting them by as much as 30 percent.

Some options industry insiders say the ISE will find it harder to attract business as a result. "You have seen heightened competition among the options exchanges in the past year," said Dale Carson, a spokesman for the Pacific Exchange. "The fundamentals of their [the ISE's] business model have been undercut by changes."

Options trading has changed more in the past 18 months than it had in the previous 200 years, Carlson continued. The other exchanges will quickly follow Philadelphia Stock Exchange's suit in reducing their costs to zero, he thinks. So the ISE will find it hard to deliver on its promise of cutting exchange costs 30 percent to 50 percent. "With exchange costs headed to zero, 30 percent of zero is still zero," Carlson said.

Whether the ISE has the liquidity necessary to support a steady options market will be the big question, he said. The ISE also has to prove that its price discovery is reliable, so its brokerages feel confident they're getting the best price every time their trades are executed, Carlson said.

That Goldman and Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, two of the three largest options-trading houses, have signed on goes a long way to guaranteeing a liquid market, ISE executives say.

Carlson counters it remains to be seen how much business they route to the ISE. "Essentially a lot of these firms are buying a call," he said. "I'm going to put my oar in the water just in case the boat starts to float."

Increases in volume will be good for all

If and when the ISE does start trading, Katz and Krell say, they'd be happy if they carve out 20 percent market share. But they admit that may take some time, perhaps three years. Until then, Katz said he expects the exchange to keep a relatively low profile, hoping to establish itself before it starts tooting any horns.

And the ISE will keep working to develop its electronic systems, keeping its staff small, without paying too much attention to what the competition is up to. "We've got a Silicon Valley mentality, a startup feel, long days, weekends -- that's the culture we want to promote," Krell says. "We've never really looked at what anybody else was going to do."

He points out that options volume has increased substantially since Porter walked into his office and floated the idea of the ISE. "We've always felt that added competition, reduced cost, more efficiency would grow the market overall."

That brings good news for all the options markets, including the ISE, he believes. Back when the four founders helped float the idea of the ISE, "we said options volume would double in two years. We were wrong. It doubled in six months," Krell said. "We think it will double again."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|