|

It's the economy, stupid

|

|

October 11, 2000: 4:02 p.m. ET

Higher rates are what are affecting stocks. The question is: by how much?

By Staff Writer M. Corey Goldman

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - It's the economy, stupid.

Those four words, a catch phrase that rolled off the tongue of soon-to-be-replaced President Bill Clinton during his 1992 campaign for the White House, became the motto uttered by Wall Street brethren and Main Street minions alike some eight years ago to describe the need to boost growth, reduce inflation and eliminate the deficit to make the U.S. economy healthy.

Now they seem to be all but forgotten. As the Nasdaq composite index shuffles its way dangerously close to the hibernation cave, investors and analysts alike are scratching their heads, pondering exactly how U.S. stocks -- particularly those of technology firms with such promise for stellar profits -- have managed to turn so quickly and decisively on a dime. Where is the revenue? Where are the profits? Why are stock prices falling so far, so fast? Now they seem to be all but forgotten. As the Nasdaq composite index shuffles its way dangerously close to the hibernation cave, investors and analysts alike are scratching their heads, pondering exactly how U.S. stocks -- particularly those of technology firms with such promise for stellar profits -- have managed to turn so quickly and decisively on a dime. Where is the revenue? Where are the profits? Why are stock prices falling so far, so fast?

"It really is the economy -- um, stupid," chided Rob Palombi, a senior economist with Standard & Poor's MMS in Toronto. "Seriously, what we are feeling now is what the Federal Reserve started doing a year and a half ago when they began raising rates. It is because of what the Fed has done that the stock market has started to come back the way it has."

For months and months, in speech after speech, Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan warned that the wealth effect -- where surging equity prices have bolstered Americans' confidence about their economic situations -- could derail the record U.S. economic expansion. The wealthier consumers feel, his argument went, the more they will spend, the faster the economy will grow and the higher prices will rise.

Dousing the wealth effect

To douse that wealth effect, Greenspan and his colleagues raised interest rates -- a move meant to boost borrowing costs and make consumers and businesses more leery about spending money. The Fed would never admit it was trying to rein in the stock market, but analysts agree that heady stock values have more than likely factored into the Fed's thinking.

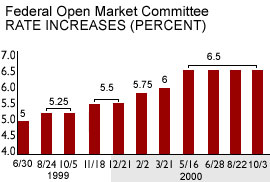

The last rate increase was a double-dose in May, when the Fed lifted its trend-setting fed funds rate to 6.5 percent from 6 percent. It left rates unchanged at its June, August and October meetings.

All that time companies continued to post stellar profits, prompting investors to pour even more cash into stocks despite earnings multiples to the moon and the expectation of slowing demand. All that time companies continued to post stellar profits, prompting investors to pour even more cash into stocks despite earnings multiples to the moon and the expectation of slowing demand.

Now, the effects of those rate increases are starting to be felt -- in the form of profit warnings from some of Wall Street's best-known firms. Yahoo! (YHOO: Research, Estimates), Lucent Technologies (LU: Research, Estimates) and Motorola (MOT: Research, Estimates) are but three that came clean Wednesday. At least 60 companies warned last week that financial results will come in lower than expected, with Dell Computer (DELL: Research, Estimates), Office Max (OMX: Research, Estimates) and Xerox (XRX: Research, Estimates) among the most prominent.

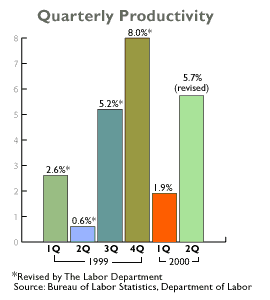

"I would have thought people would have changed their earnings expectations given that higher rates were expected to slow growth," said Drew Matus, an economist with Lehman Brothers. "The expectation all along was that because of productivity growth, companies would be able to keep boosting their profit margins, even if they weren't producing as much in goods and services, but that's obviously is not the case."

Productivity not the savior

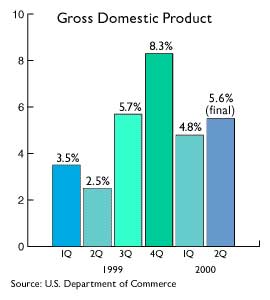

Fueling the U.S. economy's blazing performance in recent years has been incredible advances in technology -- everything from smaller and faster computer chips to wireless telephones to new and innovative ways to move information quickly from one end of the world to the other. Worker productivity advanced at a revised 5.7 percent pace in the second quarter; GDP grew at a 5.6 percent pace.

While those kinds of products and services have fueled productivity and allowed the economy to grow at an impressive, non-inflationary pace, the productivity gains all along fueled expectations for higher corporate profits, a theme that spurred the Nasdaq to multiple records and spawned a giddy glee on Wall Street and Main Street that encouraged consumers to spend. While those kinds of products and services have fueled productivity and allowed the economy to grow at an impressive, non-inflationary pace, the productivity gains all along fueled expectations for higher corporate profits, a theme that spurred the Nasdaq to multiple records and spawned a giddy glee on Wall Street and Main Street that encouraged consumers to spend.

At least until recently. Now companies suddenly are finding it much more difficult to keep up those productivity gains, particularly with much more product to sell and much less business out there willing to buy it. Hence the profit warnings in spades from some of the country's leading companies, technology and otherwise.

Of course, higher rates do not immediately stop people and businesses from borrowing money -- especially when they go up only a little at a time. Like water that comes to a boil, rising rates take time to make their presence felt; a quarter-point increase in rates by the Fed typically takes 12 to 18 months to have a material impact on economic growth.

But now, it seems, investors are feeling like the frog left in the pot.

Will the Fed ease?

Since touching an all-time high of 5,048.63 on March 10, the Nasdaq has fallen about 36 percent; since Labor Day the tech-heavy index has declined more than 20 percent. Even as the index recovered Wednesday from a 137-point intra-day loss, analysts were still cautious about whether stock prices have reached rock bottom and are poised for recovery -- again.

The Dow Jones industrial average is down 9 percent on the year, while the S&P 500 is about 7 percent lower for 2000.

So where is the economy going? According to the International Monetary Fund, the U.S. economy is expected to expand at a 5.2 percent pace this year, a point more than its annual advance of 4.2 percent recorded in 1999 even with all the Fed's handiwork. For 2001, when those rate increases begin to take hold more firmly, growth is expected to slow to 3.2 percent. So where is the economy going? According to the International Monetary Fund, the U.S. economy is expected to expand at a 5.2 percent pace this year, a point more than its annual advance of 4.2 percent recorded in 1999 even with all the Fed's handiwork. For 2001, when those rate increases begin to take hold more firmly, growth is expected to slow to 3.2 percent.

Of course, the other million-dollar question is where the Fed is going. In October 1987, when U.S. stock markets hit the skids, the Nasdaq posted a one-week drop of more than 17 percent -- a move that prompted the Fed to quickly begin lowering short-term rates. It lowered the fed funds rate to an average 6.58 percent by February 1998 from an average 7.29 percent.

Almost no one expects the Fed to do that this time around. The majority of analysts and economists on Wall Street don't expect the Fed to alter interest rates at its Nov. 15 meeting and through the remainder of this year, according to a survey of major Wall Street dealers conducted by Reuters.

Is it the economy again, stupid?

"I think the Fed will stay vigilant until the growth rate slows or until we see negative numbers on inflation," said Robert Heller, executive vice president of Fair Isaac, a San Francisco-based technology credit advisement company and a former Fed governor. "Only if we had a real stock market rout would they say, 'OK, time to hold your powder right now.'"

With almost half of America the proud owner of some stock or mutual fund, the direction of the economy and the stock market is of utmost concern as they get ready to mark their ballots in next month's election. With almost half of America the proud owner of some stock or mutual fund, the direction of the economy and the stock market is of utmost concern as they get ready to mark their ballots in next month's election.

According to a CNN/USA Today/Gallup tracking poll conducted Tuesday, Texas Governor George Bush holds a narrow lead over his Democrat opponent, Vice President Al Gore. The survey of 790 likely voters, conducted October 7-9, shows Bush with 47 percent and Gore with 44 percent.

"There is a concern in the market for some stagflation -- where demand for goods and services falls as prices go up," said Lehman's Matus. "I personally think that what happens with the market in the next few weeks will play a significant role in the election and expectations for the economy."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|