NEW YORK (CNN/Money) -

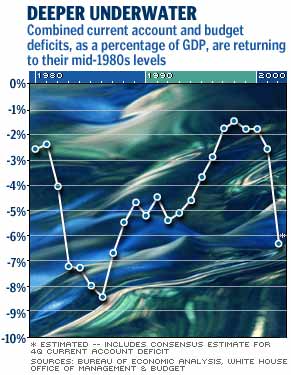

The twin terrors of the 1980s, the U.S. deficits in trade and the federal budget, are nearing record highs again.

While that could spell bad news for the U.S. economy -- especially if overseas investors flee U.S. assets and cause an '80s-style plunge in the dollar -- most analysts say that's not the most likely scenario.

Later this week, the government will report on the nation's current account, which measures merchandise trade as well as the flow of money to and from other countries, for the fourth quarter and all of 2002.

Economists, on average, think the current account deficit swelled to $136.8 billion in the quarter, according to a recent Reuters poll, which would push the full year gap to $504 billion, the largest since the Commerce Department started keeping records in 1960.

Meanwhile, the federal budget picture has plunged underwater, swinging from a $127 billion surplus in 2001 to an expected deficit of $158 billion in 2002.

That would put the combined current account and budget deficits at roughly $660 billion in 2002, easily the highest dollar amount in the nation's history for the "twin deficits."

Even relative to the economy, the deficits are growing to historic levels. That $660 billion would have accounted for about 6.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) last year, the highest since the record 8.4 percent set back in 1986. GDP is the broadest measure of the nation's economy.

In 2003, the picture is likely to get worse. Government spending -- on war and rebuilding in Iraq, homeland security, tax cuts or other measures meant to goose the moribund economy -- will create the biggest budget deficit in U.S. history. Together with a current account deficit that seems unlikely to fall much, the "twin deficits" could well become the biggest ever relative to the nation's $10 trillion economy.

"We expect the twin deficits to continue to expand in sync this year," UBS Warburg senior economist Susan Hering wrote in a recent research note. "If, as we expect, President Bush pushes ahead with both an invasion of Iraq and more fiscal stimulus, the budget gap would likely climb to $300 billion, or 2.75 percent of GDP.

"And the trade and current account gaps likely would veer toward 5.5 percent and 6 percent of GDP, respectively," Hering added. So if UBS Warburg's forecasts are correct, the combined budget and current account deficits will be more than 8.75 percent of GDP this year, eclipsing the 1986 mark.

Could consumers suffer?

So why worry about deficits?

They're a sign that the United States has been living beyond its means, like a family that owes too much on its credit cards and also keeps buying stuff from neighbors that they can't make themselves. Normally, modest budget and trade deficits aren't too much of a threat, economists believe, as long as investors in other countries are willing to finance our spending spree.

They gladly did just that in the late 1990s, when everybody and their grandmother wanted to buy U.S. technology stocks, Treasury bonds and other U.S. assets. All those shares of JDS Uniphase (JDSU: Research, Estimates) and other bubble darlings had to be purchased with U.S. dollars, and demand for greenbacks led to a stunning run-up in the value of the dollar.

But since that bubble burst there has been a sharp drop in demand for U.S. assets. Meanwhile, the money flowing from overseas has switched from productivity-enhancing spending on new technology to less useful spending on bombs, houses and SUVs, meaning the United States is doing less to build its future debt-paying capacity.

"The dollar has been depreciating, and that leads investors to expect it will continue to depreciate," said Sung Won Sohn, chief economist at Wells Fargo & Co. "That may discourage foreign investors, including foreign central banks, from buying dollars or dollar-denominated assets."

Some economists worry that, in order to keep money flowing into the United States, asset prices might have to fall further, making dollars -- which have already lost 17 percent of their value against a basket of other currencies in the past year -- even cheaper.

Meanwhile, interest rates could be forced higher as the deficits rise and investors become more nervous about parking their money in the United States.

| Related stories

|

|

|

|

|

"Global investors are advancing us about $1.5 billion a day," Northern Trust economist Paul Kasriel said. "Will they want to continue to advance us that amount on the same terms in the future? If they decide against that, then the dollar will trade off, stock prices would fall and bond yields would rise because they're saying, 'We're not going to advance you money on the same favorable terms.'"

Some economists worry the combination of falling stock prices, higher interest rates and higher inflation could spell big trouble for consumer spending, which fuels two-thirds of the nation's GDP and so far has propped up the economy.

"Twin deficits don't push us into a dark abyss," UBS Warburg senior global economist Paul Donovan said. "But they could be a contributory factor to a decline in consumer confidence, which would be enough."

The economy, limping along after the recession that began in 2001 probably ended last year, has been thrown for another loop lately by rising oil prices and concerns about a possible war in Iraq. If a dollar decline seriously hurts consumers, another recession would almost certainly follow, many economists say.

Reasons to ignore the deficits

On the other hand, though twin deficits led to a 30 percent drop in the dollar's value in the mid-1980s, the economy kept growing, with annual GDP expansion not falling below 3.4 percent between 1985-87.

If stock prices jump and oil prices fall after a short war in Iraq, as many economists hope, then the potential negatives of the twin deficits could be washed away, leaving behind only a weaker dollar that would make U.S. exports more competitive overseas.

"Maybe foreign investors are investing less in the United States than in past, but if we have a pickup in exports, the two factors offset and there's no real major problem," said Anthony Crescenzi, bond market strategist at Miller Tabak & Co.

But some economists also worry that higher budget deficits will force the federal government to borrow more, crowding out other borrowers and forcing interest rates higher. Yet others note that bond yields recently have fallen to record lows, just months after the Bush administration first said it expected record budget deficits in coming years.

"There's been a half-trillion-dollar shift in the budget story in the United States this year, but there's been no impact on rates," Crescenzi said. "People are still worried about losing money in the stock market, and they think inflation will be headed lower when oil prices fall after Iraq is resolved."

In any event, growing deficits don't seem to have caused the decline in the dollar and stock prices -- after those assets soared in the late 1990s, a decline in both was inevitable.

"The current account deficit is the most overrated economic indicator available," said interest rate strategist Rory Robertson of Macquarie Equities (USA). "We've been highlighting the potential for equity prices and the dollar to fall further, not because of the current account deficit, but because booms tend to end badly."

Despite the pain, many economists think continued weakness in overseas economies and markets could force many investors to see the United States as the lesser of two evils, meaning it's unlikely they'll pull funds from the U.S., which in turn means the twin deficits may be manageable.

"Global growth will have to be rebalanced over the next period of years, with more demand emanating from other parts of the world," said Joshua Feinman, chief economist at Deutsche Bank Asset Management. "Part of that has already started with U.S. domestic demand slowing, but the other piece hasn't fallen in place.

"There's not enough demand in other parts of world -- namely, Europe and Japan," he said, "and I don't see any catalyst for that now."

|