|

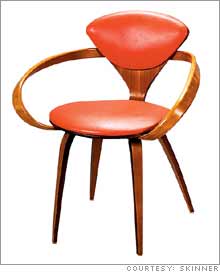

| Norman Cherner Chair, 1958. Estimated retail $1,000. Sold at auction for $650. |

|

|

|

NEW YORK (MONEY Magzine) -

Unless you're the kind of person who can afford to buy Old Masters indiscriminately, you might think of live auctions as being only for the rich and famous.

But what the world's high rollers don't want you to know is that auctions often feature everything from fine antique furniture to rare memorabilia to timeless jewelry at what amount to wholesale prices.

It's not exactly like shopping at Target, of course -- get carried away in heated bidding and you could end up paying more than retail, plus you have to remember that there's always a 20 percent sales commission tacked on to your winning bid.

But armed with a little discipline and a basic knowledge of the way auctions work, you can walk right in, place a winning bid and furnish your dining room for less than you would if you'd clicked on something at potterybarn.com.

Major auction houses -- Christie's, Sotheby's, Bonhams & Butterfields and Skinner among them -- are increasingly courting first-timers by staging a variety of lower-priced, multicategory sales that offer newcomers an opportunity to get their feet wet by bidding on art, antiques, housewares and memorabilia that may start as low as $100.

"You don't have to be a millionaire to buy at auction," says Christie's spokesperson Andrée Corroon, who adds that a recent internal survey found that 75 percent of lots sold by Christie's in the United States went for $5,000 or less.

That may come as a surprise, given that highly publicized prices for rare items tend to foster an impression of auctions as the sole province of well-heeled collectors.

"You'll never read a headline that says 'Skinner Sells Chair for $200,'" says Catherine Riedel of Skinner Inc., a Boston-based auction house. "But it happens all the time."

A few recent examples from the West Coast auction house Bonhams & Butterfields: A pair of 1930s leather-and-sycamore armchairs from France, appraised at $1,000 to $1,500, left the building for $825; a vintage 18K gold Patek Philippe wristwatch with a retail value of $18,000 sold for $7,050; an entire dining room's worth of 19th-century Gothic furniture -- eight chairs, a table, a side cabinet, a buffet, a side table and a wall cabinet -- sold for $8,225 (estimated retail value: $20,000); and a 1986 Rolls-Royce Silver Spur -- a cream puff and a near classic, valued at $35,000 -- drove off for $23,800, roughly the price of a Kia minivan. In 10 years, you'll still be able to sell the Rolls. The Kia? Good luck.

Americans spent more than $217 billion at live auctions last year, a 6.8 percent increase over 2003, according to a report prepared for the National Auctioneers Association. There's a sense in the industry that cultural phenomena such as eBay and PBS' "Antiques Roadshow" have goosed public interest in traditional live auctions.

"Those things have absolutely had an impact on our business," says Riedel. "People's curiosity level is higher these days."

With each bid, of course, comes the chance that you'll get carried away. "In the hype of an auction, you can end up paying too much," says Edward Wilkinson, an auctioneer, art dealer and consultant in Los Angeles. "But if you have a clear understanding of what you're doing, you can do very well."

In the interest of the latter, a guide to doing well.

Finding an auction

Auctions range from mom-and-pop country antique sales to multimillion-dollar affairs. The auction you pick will depend, naturally, on what you want to buy.

The Web sites of established auction houses list upcoming sales by genre, and the houses will send you catalogues listing the lots to be sold, along with blurbs describing their provenance and condition and listing estimates. (Some post details online.)

Independent auctions, meanwhile, typically advertise in the classified section of local newspapers or in arts and antiques magazines. The majority of auctions are free and open to the public, and you're generally welcome to waltz in, sit down and observe, whether or not you're registered as a bidder. Newcomers should take advantage of this opportunity to get a feel for how things work.

Getting ready

Should you wish to bid, you usually have to register before the sale. There's some paperwork to fill out prior to the auction day, sometimes a credit check, and then you'll be issued a bidder number that will identify you throughout the auction.

If you plan to bid in person (as opposed to online or over the phone, as some auction houses allow), you'll get a paddle with your number on it, which you raise to signal a bid to the auctioneer.

Doing your homework

In addition to publishing the catalogue, most houses hold live, open-house-style previews during which the items to be sold are on display. You can examine them up close and ask questions of specialists -- either experts employed by the house or, if it's a small, independent auction, the auctioneer himself.

Goods are generally sold "as is"; once the hammer falls, you own what you've successfully bid on, which means you'd better notice that scratch or those wobbly legs before you buy. Attend previews if possible and examine closely anything you might be interested in.

Large auction houses will supply you with a written condition report upon request. It's not legally binding, but it will list known damage and any known repairs that may not be obvious to an untrained eye.

Running the numbers

The estimate, which is usually expressed as a range (say, $500 to $800), represents the auctioneer's guess as to what the item -- or, in auction parlance, lot -- might sell for. Of course, estimates are just that. Some lots far exceed the estimates, and indeed, estimates tend to be conservative.

Why? Marketing. "Conservative estimates encourage bidding," concedes Skinner's Riedel. Use them as a guide, but know that they're more likely to be low than high.

The other number you'll need to think about is the reserve, a confidential price preset between the consignor and the auction house, below which a given lot will not be sold. As a matter of ethical practice (and often, state law), the reserve, though secret, cannot exceed the low end of the estimate.

The auctioneer may bid against you on behalf of the seller up to the amount of the reserve. He may call out a bid and then say "My bid," a signal either that the reserve has not yet been met or that he is bidding for someone who is unable to attend.

Bidding smart

The single most important advice in bidding is to decide ahead of time what your top bid will be -- and to stick to that like superglue. (In calculating your final bid, be sure to take into account the buyer's premium -- usually a markup of as much as 20 percent that goes to the auctioneer or auction house -- as well as any sales tax.) In the hype and competitive heat of an auction, it's easy to let your ego seize control of your wallet.

Auctioneers know this and will give you every opportunity to spend more money. It's part of the game.

"You can tell when someone's interested in a lot -- their body language, the way they hold their paddle, how attentive they are," says Ed Beardsley, an auctioneer for Bonhams & Butterfields in Los Angeles. Experienced buyers tend to hold off until the bidding is winding down. By jumping in early, you risk driving up the price.

And don't worry: Sneezes, twitches and other fidgets are unlikely to be mistaken for bids, despite the fears of first-timers.

Taking it home

At the end of the sale, if you've been a successful bidder, you'll need to pay for your purchase and take it home. Checks are the traditional method for settling purchases at auctions, credit cards are sometimes accepted, and cash is always welcome. You'll pay the amount of your winning bid plus the aforementioned buyer's premium, as well as sales tax on that total.

Bear in mind also that removing your purchase is your responsibility. If you have your eye on something large or unwieldy, think about how you'll move it and how much that will cost. If you have to pay someone to transport the armoire, you risk negating the great deal you got on it. And scoring the deal, after all, was the reason you bought it at auction in the first place.

Interested in the job of auctioneering? Click here.

|