NEW YORK (Fortune) -- In March 2006, the Tennessee board that regulates cemeteries got a five-page complaint, in neatly penned cursive longhand, from Geraldine Story, an elderly Memphis woman. Story's husband Ralph had died on January 22. In preparation for that day, he and she had each, more than thirty years earlier, purchased prepaid funeral services from the Forest Hill Funeral Home in Memphis, to make sure that each's burial expenses would not be a burden to the other or to their families.

Six hours before her husband's wake, however, Story learned that the casket would not look anything like the bronze one promised in the contract. Instead, it would be made of brown painted wood, with "a single latch on the lid that resembled a cheap tool box," as she wrote. If she wanted an upgrade, the least expensive alternative would run $3,995.00.

|

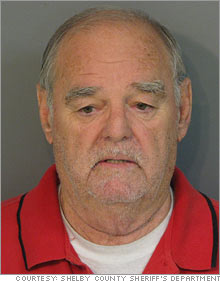

| Clayton Smart is incarcerated at the Shelby County jail in Memphis awaiting trial. |

She bought that one, of course, but after the funeral she followed up and was eventually told by a candid funeral home staffer that the funds set aside to fulfill her contract had been "skimmed off the top several times," and now the home was stuck with more than 13,000 "pre-need" contracts just like hers with no way to pay them. "He said they had to operate the way they are doing," she wrote, "or go out of business in two months and we don't want that, do we?"

The then-unraveling scam that victimized Ms. Story turned out to be worse than that, even. The same folks who looted Forest Hills, according to Michigan authorities, were also looting trust funds from 28 cemeteries in that state (including the final resting places of Rosa Parks and Henry Ford).

Tennessee authorities estimate that the embezzlers dissipated $20 million from Forest Hill's trust funds, while Michigan authorities allege that they took up to $70 million from Michigan's - about 31 percent of that state's total cemetery trust funds.

The two most culpable parties, according to prosecutors and state-appointed receivers, are an odd couple: a 67-year-old oil and gas speculator from Okmulgee, Oklahoma and a 41-year-old senior vice president for Smith Barney Citigroup, who lives in 5-bedroom, 8,000 square-foot home in the tony Philadelphia suburb of New Hope.

Clayton Ray Smart, the speculator, is now incarcerated at the Shelby County jail in Memphis, awaiting trial on a felony indictment, handed down in April, for theft, conspiracy and money laundering. He's also awaiting extradition to Michigan, where he faces a 39-count felony complaint, issued two days after Tennessee's, for racketeering and embezzlement.

Mark Singer, who worked until February in the Newtown, Pennsylvania, field office of Smith Barney - now, formally, Citigroup Global Markets - is a co-defendant in the Tennessee case, though he's free on $1.25 million bond. (He is not charged criminally in Michigan, but is named in civil suits both there and in Tennessee.) Both men have pleaded not guilty.

Through the chief jailer, Smart declined to comment for this article. (Most of his assets have been frozen, he claims to have no cash and he is representing himself.) Singer did not respond to an email or to a voicemail left at his home, and his criminal defense lawyer, Zachary Fardon of Latham & Watkins's Chicago office, declined to discuss the charges against him, citing Tennessee rules restricting attorney comment on pending cases.

What follows is the story of what appears to have been a truly dastardly scam, as best the Tennessee and Michigan authorities have yet been able to piece it together. It's not for the squeamish.

Hatching a plan

In September 2003, Clayton Smart, known by some as "the Colonel," met with a Bloomfield, Michigan, attorney named Craig Bush to discuss acquiring the 28 Michigan cemeteries that Bush then owned. Some cemetery staffers remember Smart telling them that he thought he could make the cemetery trust funds "work better," according the Michigan indictment.

To gather money for the a down payment, Smart, with assistance from two associates, borrowed $5.4 million from a Houston lender in January 2004. About ten months later the lender sued Smart and his two associates for civil fraud in Texas, claiming that they were still owed $3.1 million and that the collateral they'd been given was fraudulent. The suit is still pending, but each of Smart's two business associates has subsequently been convicted of unrelated federal crimes and each is now serving a prison term. (One is doing 57 months for wire fraud and forgery in Florida, while the other is serving 78 months for defrauding a pension fund in Iowa.)

To assure Bush that he could afford to make good on the full price for the cemeteries - $35 million - Smart allegedly had yet another associate, Carter Green, send Bush a letter stating that Green was in the process of liquidating a $100 million Treasury note to help finance the purchase, according to the Michigan indictment. Bush soon discovered, however, that there is no such thing as a $100 million Treasury note, and that the letter was a deception.

Nevertheless, Bush continued negotiating with Smart, closing the sale on August 19, 2004, for $35 million, most of which was paid in notes. (Green was arrested Wednesday by the Michigan attorney general's office and charged with racketeering, forgery and being an accessory-after-the-fact in the cemetery embezzlement scheme; at press time he was jailed in Detroit.)

Formally, the buyer of the cemeteries was Indian Nation LLC, which managed the cemeteries through an entity called Mikocem, which meant "King of Cemeteries." (Miko means king in Chickasaw, one of the Indian tribes near Okmulgee.) Indian Nation was 95 percent owned by Smart and 5 percent owned by his lawyer, Stephen Smith. Smith has been charged as a co-defendant in the Tennessee indictment and has pleaded not guilty.

(In a telephone conversation from his home near Henryetta, Oklahoma, Smith says Smart didn't consult with him on what he did with the businesses, and that Smith's main role was setting up Smart's companies and performing other ministerial tasks. He says Smart gave him ownership interests in the businesses in lieu of attorneys fees.)

When the Michigan cemeteries changed hands, they had $61 million in trust funds associated with them. In Michigan, as in almost every other state, for-profit, perpetual-care cemeteries are required by law to maintain a variety of funds in trust to ensure that there will be sufficient money to care for the cemetery grounds in perpetuity. In those states that permit pre-needs burial contracts, cemeteries must also set aside large percentages of the contract purchase price to ensure delivery of all of the services and merchandise (caskets, markers, vaults) promised.

As soon as the deal closed, Smart had the trust funds transferred from a bank in Michigan to Singer's Smith Barney field office, according to a suit brought by Michigan cemetery commission Andrew Metcalf. In September alone, a Michigan state auditor found, Singer, at Smart's direction, disbursed about $12 million of cemetery trust funds to a Smith Barney account owned by Craig Bush, while another $10 million found its way to Bush in subsequent months.

The Michigan conservator alleges, in other words, that Smart was paying for the cemetery by looting the cemetery's own trust funds. (Bush has not been charged criminally. The Michigan conservator has sued him civilly, however, and has seized $22 million from his accounts. Bush's attorney did not respond to an email inquiry seeking comment.)

Ultimately, the Michigan auditor concluded, about 45 percent of the Michigan trust funds ($31 million) went to a corporation called Quest Minerals and Exploration that Smart controlled, though it was ostensibly owned by his wife's aunt. (Smart's stepdaughter was an officer and co-defendant, Smith was a director and corporate secretary.)

Another 54 percent of the trust moneys were placed into high-risk, illiquid hedge funds, which Michigan authorities say were obviously not appropriate "prudent" investments for cemetery trust funds. Of the latter, about $7 million went into a legitimate Cayman Island-based fund called The Topiary Trust, while another $25 million went to a outfit called Fondren Investments, a Nevada firm associated with Smart's associate Green, the documentation for which was characterized as "substandard" and "irregular" in court filings submitted by Michigan cemetery commissioner Andrew Metcalf.

Dirty money

Most of the money that went to Quest - whose oil and gas leases had a market value of only $106,000 - did not did not stay there, but was either forwarded to Bush (as partial payment for the cemeteries) or disbursed to other destinations. Because of the large number of partnerships and corporations that Smart controlled, the Michigan authorities aren't certain where all the money went, but they believe it likely that at least some of it was used to fund Smart's December 23, 2004, acquisition of the Forest Hill Funeral Home and Memorial Lawns in Memphis. Forest Hill controlled three cemeteries and funeral homes in Tennessee, as well as several cemeteries in Arkansas.

When Smart bought it, Forest Hill had about $29 million set aside in statutorily required trust funds. Most of Forest Hill's trust moneys - about $22 million - had been invested in insurance policies which guaranteed that when the purchaser of a prepaid burial contract died there would be sufficient money there to fulfill the contract. Smart quickly had all those policies cashed out. Since their surrender value was much lower than their face value, cashing out immediately depleted the trust value by $9 million.

The cash from the Tennessee trust funds was transferred to a wide variety of destinations, including companies associated with Smart's Michigan cemeteries, a custom horse-trailer company Smart ran, the sons of two of Smart's incarcerated former business associates, Smart's own son and several accounts controlled by Singer at Smith Barney.

About $2.5 million ultimately found its way to an account Singer had at Greenlight Capital, a hedge fund and private equity firm led by activist investor David Einhorn, while about $6.3 million were allegedly invested in Kinglier Capital, a partnership in which Singer and his wife were allegedly principals. (Greenlight is not suspected of any wrongdoing, according to an attorney at Tennessee conservator Max Shelton's office.)

Though required by law to make regular fresh deposits into trust funds, Smart failed to do so, each state claims. (Michigan says he owes more than $9 million in overdue deposits.) Smart was also failing to make the many regular financial filings required of participants in this heavily regulated industry.

Inside man

Knoxville man Jason Strader, 34, says in an interview that Smart hired him in September 2005 as part of the effort to get the cemeteries' financials in order - they hadn't been updated since March, he recalls - and he stayed there until February 2006. Strader says alarm bells began going off for him when, at some point, Smart instructed him to use cemetery funds to pay expenses relating to vehicles owned by Quest - the Oklahoma oil and gas exploration company.

Strader also says that while he was working for Smart he would often communicate several times a day with Singer, who was then trying to obtain loans from banks. Strader claims that Singer asked him to alter financial statements to make them appear more comforting to lenders. (Singer's attorney, Fardon, again declines comment, citing Tennessee's rules restricting attorney comment on pending cases.)

Strader left the company on February 10, taking his laptop with him, which held copies of hundreds of company documents and emails. According to Strader and his attorney, Charles Currier, they then together contacted the Tennessee attorney general's office and a federal IRS agent to report what they knew. The Tennessee authorities contacted the Michigan authorities, they say.

That same month, even as the rickety scheme seemed to be caving in from every direction, Tennessee authorities contend that Smart and Singer used trust funds to make a down payment on the purchase of a $3 million Raytheon Turbo Jet aircraft. The jet was being purchased in the name of an insurance company Smart wanted to set up offshore. Strader says Smart hoped to sell pre-needs burial insurance policies enabling him to control how the premiums would be invested.

By March 2006, however, the Tennessee and Michigan attorney generals had each initiated criminal investigations, and in late April the Detroit News broke that news publicly. Smart denied any embezzlement to newspapers, blaming the charges on a "disgruntled" former employee.

Nevertheless, on July 6, Smart had no choice but to convene a press conference to announce that Forest Hill could no longer honor its 13,465 prepaid policies, and that, from that point forward, those customers would have to pay a $4,000 "service" fee.

"Obviously things were a lot cheaper in 1965," Smart was quoted saying in The (Memphis) Commercial Appeal, "but inflation has struck, and we could not continue to stay in business if we honored those policies now."

The announcement was met with outrage, and the first of at least four civil class actions was filed against Smart and Forest Hill less than a week later.

The Michigan cemeteries were finally placed into receivership in December, and Tennessee's were seized by the Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance in January 2007.