Search News

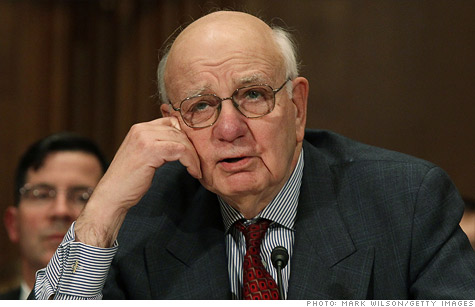

Obama economic advisor Paul Volcker says the namesake rule, which aims to ban risky trading by banks, will limit future federal bailouts.

Douglas J. Elliott, who worked as an investment banker for two decades, is a fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Now we have one more thing for which to blame Goldman Sachs (GS, Fortune 500).

Their latest public relations problem has given added impetus to supporters of the Volcker Rule, the part of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law intended to force banks out of "proprietary trading."

The activities which were denounced are not covered by the Volcker Rule, but that's not stopping politicians from drawing spurious connections, taking advantage of Goldman's terrible public image.

While I am a strong supporter of Dodd-Frank, this part of the law is fundamentally flawed and will do considerably more harm than good for the economy.

The core problem is the Volcker Rule purports to eliminate excessive investment risk at banks without measuring either the level of risk or the capacity of banks to handle it, which would tell us whether the risk was excessive.

Instead, the rule focuses on the intent of the investment.

This subjective and vague approach means the Volcker Rule will do a poor job of identifying or eliminating excessive investment risk, will be costly even when it correctly identifies risk, and will be even more costly when it discourages risk that is incorrectly treated as if it were excessive.

The Volcker Rule will raise the cost of credit to our suffering economy.

Securities markets will be harmed by a substantial reduction in the liquidity currently provided by banks. This will force a widening of bid/ask spreads, equivalent to increasing commissions charged to investors, and will also make new issuances of securities more expensive.

It will also raise costs and lower revenues for banks, pushing them to charge customers more in other ways.

As a result, companies wishing to invest in new plants or R&D or to hire additional workers will face a higher cost.

The decreased efficiency of markets will also spur investors to demand higher risk premiums, reducing the value of existing stocks, bonds, and other assets, potentially including housing.

There are at least four core problems with the Volcker Rule:

Measuring risk. It is unclear why we should care very much about a bank's intent.

It's the level of risk relative to the ability to bear that risk that is of prime interest.

The globally-agreed rules on bank capital requirements take a more intelligent approach, by explicitly measuring both investment risk and the adequacy of capital to absorb those risks.

It makes a lot more sense to fix any flaws in that approach than to act as if we have no ability to measure risk or capital.

Defining 'prop trading.' The concept of "proprietary investments" is a very subjective and arbitrary one.

Many supporters of the rule seem to be particularly concerned about investments made by banks that are funded with depositor money and on which the shareholders collect any gain.

However, that defines essentially any investment made by a bank, since depositor funds are basically interchangeable with all the other funds gathered by a bank. And the shareholders always benefit from any gains on investments.

I therefore surmise that the underlying rationale for the rule must be to try to separate out activities that are integral to banking from those that are not.

By focusing on investments alone, the Volcker Rule implicitly assumes that lending is good. In addition, some investment activities are recognized as integral to banking, while others are not.

This raises several concerns. For one, I do not always agree with the arbitrary choices about what is integral and what is not.

More importantly, it is often extremely hard to draw the line between acceptable and unacceptable activities. For instance, securities dealing requires the holding of securities to meet potential customer demand in a timely manner.

At what point does the inventory shift from being an appropriate size to being at a level that indicates speculation of a type the Volcker Rule prohibits?

Perhaps more fundamentally, finance has evolved over the last few decades to the point where corporate borrowers switch easily between borrowing via loans and via securities.

This means that securities activities are now integral to modern banking, just as lending has always been. Treating loans as good and securities transactions as suspect, which is implicit in the Volcker Rule, leads to bad policy.

Guessing the intent. Operationalizing the arbitrary and subjective distinctions created by the Volcker Rule forces regulators to peer into the hearts of bankers.

The proposed rules are inevitably very complex, as regulators make an honest effort to obtain enough information to guess the intent behind investment actions.

We are in danger of forcing regulators to micromanage the actions banks take in one of their core activities, the ownership and trading of securities. That raises costs and discourages legitimate activities.

High risk investments. By focusing on intent, we are almost certain to miss large swathes of investments that are taken on for an acceptable purpose, but which carry excessive risk.

Almost all of the AAA-rated mortgage-backed and asset-backed securities on which banks lost money in the financial crisis would have passed the Volcker Rule tests easily.

We will survive the Volcker Rule, but it is an unnecessary, self-inflicted wound. Congress should repeal it.

Failing that, Congress should clearly instruct regulators to stop only those activities that very clearly violate the Volcker Rule without halting activities where the intent of the transactions is unclear.

Regulators should also be encouraged to implement the rule in the least burdensome manner possible.

Nonetheless, the arbitrariness of this rule and the ambiguity of definitions necessarily produces excessive complexity. ![]()

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Overnight Avg Rate | Latest | Change | Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 yr fixed | 3.80% | 3.88% | |

| 15 yr fixed | 3.20% | 3.23% | |

| 5/1 ARM | 3.84% | 3.88% | |

| 30 yr refi | 3.82% | 3.93% | |

| 15 yr refi | 3.20% | 3.23% |

Today's featured rates: