The nature of campaigning is to make promises. The nature of governing makes it hard to keep all those promises. And so do unforeseen events, like recessions.

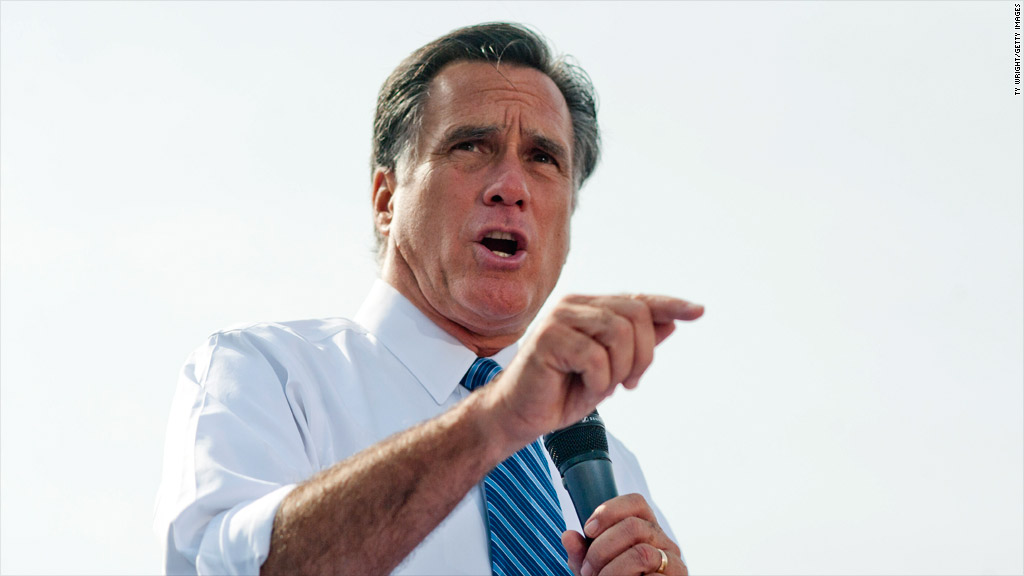

That may be why even those who broadly favor the kind of tax reform that Mitt Romney is proposing -- lower tax rates, fewer tax breaks -- worry that his $5 trillion plan might not deliver all that he's promised.

If elected, Romney says he would work with Congress to lower income tax rates by 20%, repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax and make investments tax free for everyone except those making more than $100,000 ($200,000 if married).

The rich as a group, Romney says, would continue to pay the same share of revenue they pay today, and the middle class would see its tax burden lowered.

His plan wouldn't add a penny to deficits, Romney promises, because his tax cuts would be paid for through a combination of reduced tax breaks and the economic growth his plans would generate.

Related: The facts behind Romney's tax plan

The only problem: Fulfilling those promises -- politically and practically -- is far from a sure thing.

Cutting tax breaks: To pay for any substantive rate reduction, a lot of tax breaks will have to be eliminated or significantly reduced. That means lawmakers will have to say "no" to lobbyists and constituents in their home states who have enjoyed those breaks.

Lawmakers won't have the stomach for it, said Christopher Bergin, president and publisher of Tax Analysts. "These guys have the political courage of my couch. ... I'll predict with certainty that Congress will fail [Romney]."

There's precedent for Bergin's pessimism. The last time Congress embarked on the kind of tax reform Romney is proposing was in 1986. Since then lawmakers have created dozens of new tax breaks and made the tax code even more complex.

It might be easier on lawmakers if Romney backs a cap on itemized deductions -- which he said is an option. But his campaign has said curbing tax breaks likely wouldn't be limited to itemized deductions, so a cap on them wouldn't preclude fights about other tax breaks.

Economic growth: Proponents of lower tax rates and fewer tax breaks say such a system would be more economically efficient than today's code.

To put it another way: People would start to put their money into activities and investments where it makes the best economic sense, rather than where they can get the best tax break. That, in turn, could boost economic growth and revenue.

But if Congress fails to rein in tax breaks sufficiently, Romney will have to lean very heavily on economic growth to generate much of the estimated $5 trillion in revenue that his tax cuts would cost.

If that's the case, "you're betting on a shaky horse," Bergin said.

Related: Middle class promises will be hard to keep

That's because no matter how well it's designed, tax reform won't be an economic panacea. Many factors other than taxes play a role in spurring or slowing the economy. And that has a bearing on federal coffers.

Since 2000, significant tax cuts were passed in 2001, 2003, 2006, 2009 and 2010. But there have also been two recessions. Revenue intake for nine of the past 12 years has been well below the historical average of 18.3% of the size of the economy. And for five of those years, the dollar amount of revenue actually fell from the year before.

Even elements of the tax reform itself may tamp down the growth and revenue potential. If a new measure is implemented immediately, that could be very economically disruptive. But if it's phased in slowly to avoid that disruption, the revenue that could help pay for the tax cuts may not materialize for years.