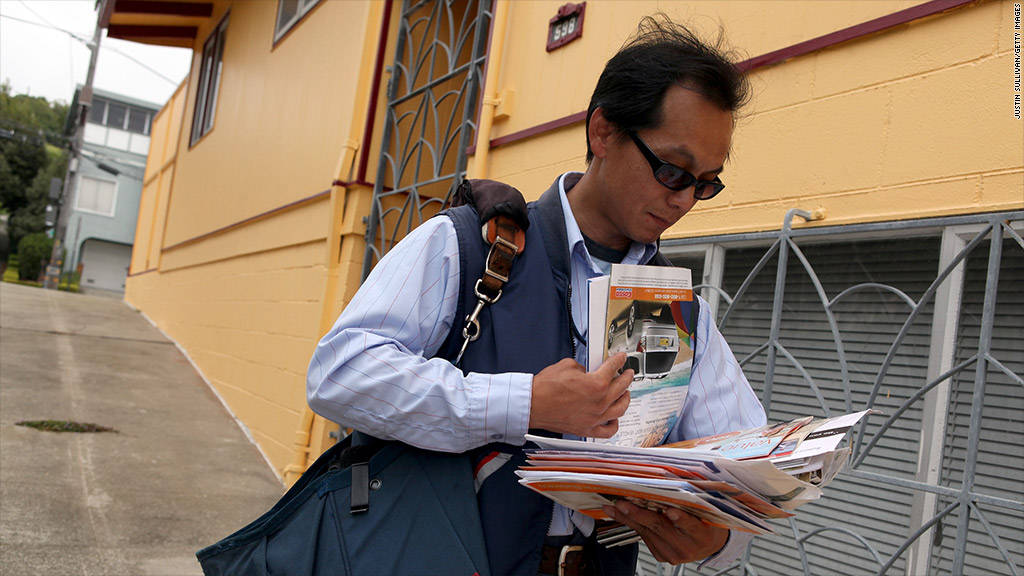

When Edward Dyer started work as a letter carrier 18 years ago in New York City, job security was one of the selling points.

"It was one of the most secure jobs that people looked up to," said the Bronx resident who has a route in Manhattan. "You didn't need a college degree, you could get a job paying a good amount of money, plus benefits that you need to raise a family,"

Dyer's job supports a family of five, and has helped pay for his oldest daughter's college tuition. Despite almost two decades of seniority under his belt, Wednesday's announcement that Saturday service is being eliminated has made Dyer fearful. He worries that the job won't last long enough to get him to retirement as he has always assumed.

"Once they do this, they can make any change they want," he said. "I don't know what it's going to turn into. Is it going to cut from five days down to four days or three days? I need another 20, 25 years to get to retirement. I don't know if it will be there that long."

Dyer's union, the National Association of Letter Carriers, vows to fight the plan, arguing the Postal Service doesn't have the authority to eliminate a day of service without Congressional approval. But the Postal Service says it has authority to go ahead with the plan, and members of Congress haven't yet said they will pursue any action to stop the agency.

Related: Postal Service to end Saturday mail service

There could be 22,500 jobs eliminated nationwide under the plan that the Postal Service says would save it $2 billion annually. The Postmaster General Patrick Donahoe said he will not lay off any workers and accomplish the cuts by cutting overtime and part-time hours and offering buy outs to current employees.

But, Dyer is nervous.

"They're eliminating one job for every five routes," he said. "In a perfect world, people who want to leave will be the ones to leave. But we don't live in a perfect world."

First class mail, the most profitable product for the postal service, has fallen by a third since the peak in 2001 amid the rise of email and electronic banking. But the key culprit for the Postal Service's financial woes has been a 2006 congressional mandate, under which it has to pre-fund healthcare benefits for future retirees. The USPS has been borrowing billions of dollars from taxpayers to make up for the shortfalls.

Opinion: Save the Postal Service from collapse

James Hunter, 48, a carrier in Bethany, Mo., said Congress has "handcuffed" the Postal Service with its pre-funding requirement. Hunter believes that the agency should be allowed to expand the services it offers customers.

As a part-time carrier, Hunter works 20 to 28 hours a week and has a 29-mile commute to his job. With Saturday delivery gone and full-time workers absorbing more hours on weekdays, Hunter said he and others in his position may be forced to reevaluate their options.

"There's going to be a lot of carriers that quit, and I think that's what they want," he said. "If a person gets cuts down to 10 hours a week or 13 hours a week, and you're trying to drive 29 miles one way with $4-a-gallon gas, you just can't do it."

Postal Service workers reached a peak of 909,000 in early 1999, according to the Labor Department. The latest reading from January shows 601,300 workers.

By comparison, just the number of jobs lost -- 300,000 jobs -- is almost as many as the total number of U.S. employees at rival package delivery company United Parcel Service (UPS), and twice the number of workers at the overnight delivery service of FedEx (FDX).

The Postal Service has been a bastion of solid middle class jobs with good benefits. According to government data, the average annual pay of the 315,000 letter carriers at the postal service is $51,390. The second most common job, the 140,000 mail sorters, get paid an average of $48,380.

CNNMoney's James O'Toole contributed reporting.