The U.S. government reportedly has a sweeping system for monitoring emails, photos, search histories and other data from seven major American Internet companies, in a program aimed at gathering data on foreign intelligence targets. But the companies say they didn't know a thing about it.

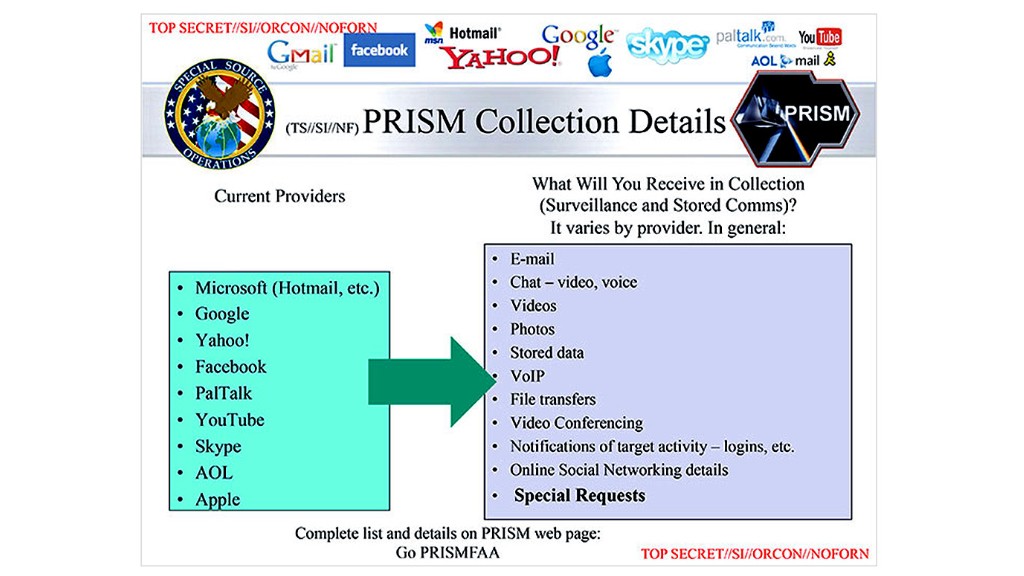

That's one of the biggest conundrums of the newly discovered National Security Agency surveillance program known as "PRISM": If Microsoft (MSFT), Yahoo (YHOO), Google (GOOG), Facebook (FB), PalTalk, AOL (AOL), Skype, YouTube and Apple (AAPL) really didn't know, how did the NSA get the data?

Theory A: It ain't what the papers say it is. The Guardian and The Washington Post may have overstepped in their analysis of the PowerPoint-style slides they obtained from an NSA source. There's a chance PRISM isn't the wide-ranging program that they reported it to be.

The Washington Post altered part of its article on Friday, removing a line saying that the tech companies "participate knowingly in PRISM operations," and both newspapers are vague about just how much data is being amassed.

The quotes they use sound scary: "They quite literally can watch your ideas form as you type," the "career intelligence officer" who exposed the program told the Post.

But can "they" -- meaning the NSA -- do that for everyone, or only for targets that they have obtained court orders to pursue? All of the tech companies listed in the Guardian and Post articles make clear in their service terms that they will hand over user data when legally compelled to do so, but several insisted very strongly that they have no "back door" system giving the government unfettered access.

" Any suggestion that Google is disclosing information about our users' Internet activity on such a scale is completely false," Google CEO Larry Page wrote in a blog post titled "What the ...?"

If PRISM still requires the government to get a court order before obtaining the information, that could explain why the companies didn't know about the program -- they're accustomed to receiving subpoenas from the government for users' data, on a limited scale.

Theory B: PRISM exists as the newspapers said, and the companies -- or at least an employee or two -- knew. The NSA's tremendous capabilities have been well documented by news outlets like Wired, which last year revealed the existence of a massive Utah data center and a secret NSA code-cracking supercomputer in Tennessee. A program like PRISM isn't difficult to imagine, and it's possible that the companies did, in fact, know about it.

All of seven of the tech companies named in the slide presentation came out with strongly worded denials. But Mike Janke, the CEO of encrypted communications service Silent Circle, thinks the companies were compelled to grant significant access to their systems based on post-Sept. 11 amendments to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, which targets foreigners of interest to the government.

"[The tech companies] are wordsmithing -- they didn't know it was called PRISM, maybe, but they were asked to provide access," Janke told CNNMoney. "Otherwise the government would be sending subpoenas every five seconds."

Janke said he's "100% sure" the government had access to the servers somehow. A telltale sign: virtually all digital communications feature some form of encryption, but the government reportedly had access to decrypted data. Most often, the encryption key is located on a company's server.

"Looking at the type of data that was included -- video chats, full emails -- the only way you can get that is by being in a [company's] central server," Janke said. "No question about it."

But the companies' denials are so firm that it seems unlikely they're all playing word games. It's possible that only a small number of people at the companies knew about the government access, noted John Michener, chief scientist at Casaba Security. Since the program was top-secret, the news could have surprised even the CEOs of firms that complied.

"It could have been an engineer or two asked to put in some special equipment, and they're court-ordered not to say anything," Michener said. "And then the CEO can say, 'Of course we didn't know!'"

If the NSA did finagle its way into the company's servers directly, someone must have known about it because it leaves a trail that's difficult to erase, said Mark Wuergler, a senior researcher at security consultancy Immunity Inc.

"If the NSA gets into your system somehow and removes all of this information, that's millions of records," Wuergler said. "That creates a massive paper trail. There's a log showing you that it happened."

Related story: NSA spying scandal: Waiting for the next shoe to drop

Theory C: The companies didn't know, and the NSA got the data anyway. The Post cited a separate classified report that claims the mining is done through networking equipment, such as Internet routers, installed at the companies' offices. Similarly, some security experts suggested the NSA could have put its own intercept devices between the companies' data centers and the wider Internet.

The NSA has a history of doing that kind of thing. The existence of "Room 641A," a secret intercept operation installed in an AT&T (T) data center in San Francisco, came to light in 2006 after a whistleblower went public.

Access through NSA-monitored equipment is a possible scenario, Wuergler said. But the companies almost certainly would have discovered what was happening in short order.

"That would be a very noisy attack," Wuergler said. "If that's what was done, and the companies truly didn't know about it, that would be a major security breach."

Wuergler said the public shouldn't be surprised by this kind of widespread monitoring. He pointed to President Obama's statements Friday about the delicate balance between privacy and protection. In short, we can't have 100% of both.

"I think that the NSA, of all agencies, has more access to our private lives than we think," Wuergler said. "It's when these little details come out that we start to panic."