Bank robbers don't rob banks anymore. They don't need guns, and they don't wear masks. Instead, they hide behind their computer screens and cover their digital tracks.

In today's world, there are multiple ways for cybercriminals to make money long before cash is actually transferred out of a bank account. Robbing a bank has become one of the last cogs in a much broader operation.

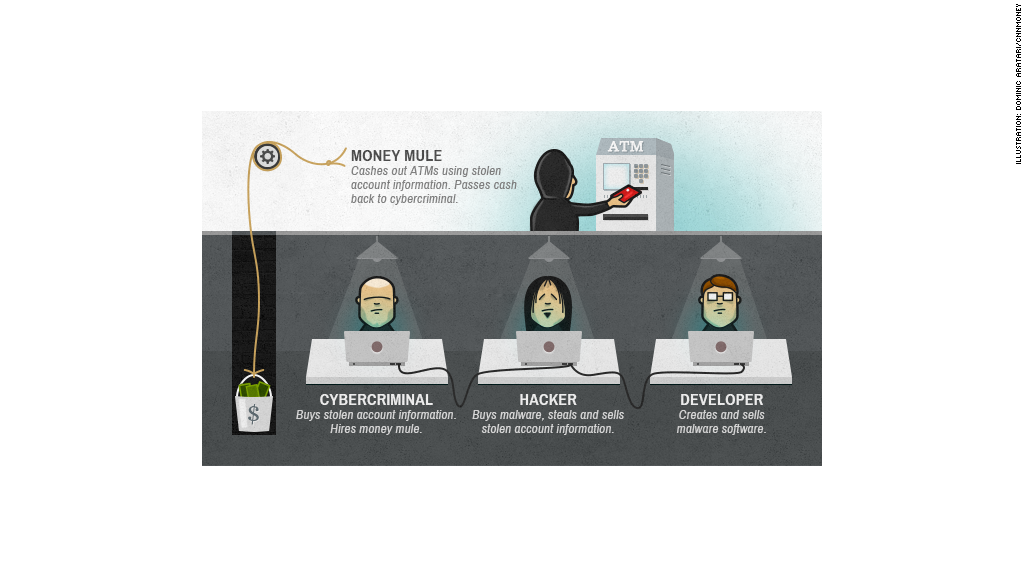

Online theft is almost always part of a much grander scheme. Though sometimes a high-skilled individual or single group of cybercriminals will handle all parts of an operation, most cybercrime is split up into several steps, each handled by a different player, according to Vikram Thakur, a principal manager at Symantec Security Response.

Most bank account thefts begin with a single malware developer who sells malicious software on an underground black market to hackers.

On those dark channels of the Internet, criminal hackers can buy tools to steal users' bank account credentials, services to bring down websites, or viruses to infect computers.

"There's more variety and more choices than me going to my local Costco," said Raj Samani, a chief technical officer at the security company McAfee.

Related story: Scenes from a $45 million bank heist

It is easier than ever before to find and use these services, Samani said. Hiring a criminal hacker is easy, because today's malware requires hackers to have little technological knowledge to infect hundreds or thousands of computers.

And some services are fairly cheap. For instance, getting a hold of 1 million email addresses can cost just $111. That means there are more and more cybercriminals hoping to get in on an operation.

Once unsuspecting victims' credentials or bank account information has been collected, hackers may resell that data to someone who repackages it in a useful way and redistributes it on the black market.

Not all information has equal value. Often criminals are looking for credentials of wealthy individuals with accounts at financial institutions where they are familiar with the security systems.

"All the mature, smart criminals sell the goods to somebody else and cut themselves out of the operation, out of the cross hairs," said Thakur.

Up to this point in the operation, no money has been stolen -- but thousands or millions of dollars have already exchanged hands.

The cybercriminal who ultimately buys the bank account information may use it to transfer money out -- but that's a much higher-risk endeavor.

At this stage of the heist, cybercriminals may hire a "money mule" to increase what distance still exists between them and the act of cashing out. Mules sometimes use international wire transfers, make online purchases with stolen credit cards or actually go to the ATM using a stolen PIN and a spoofed debit card.

Money mules are often given a small share of the takings for their work, despite the fact that they're the easiest targets for law enforcement.

"There's a huge shortage of those people because they're actually at risk of being caught," said Thakur.

Related story: 8 charged in $45 million cybertheft bank heist

Most of us have at one time or another discovered our debit or credit card was used somewhere across the country. But even if the thieves take money from your account undetected, your financial institution typically covers the loss.

"Even though the threat is substantial, it does not always translate to people losing money," said Thakur.

And the banks are getting better at stopping breaches so that it's harder for criminals to successfully take money out at all.

The number of breaches have gone up slightly over the past year, but the trend is uneven. The Identity Theft Resource Center tracked 662 breaches at both banking and non-financial institutions in 2010, 419 breaches in 2011, and 470 breaches last year.

Financial institutions have gotten 10 times better at preventing data breaches since 1990, said Doug Johnson, vice president of risk management policy at the American Bankers Association.

"It's not a straight march forward," said Johnson. "But I think we clearly recognized that electronic fraud is going to increase."