The Supreme Court was Aereo's destiny.

That's obvious now, two years after the streaming TV service came online in New York City and incurred the collective wrath of all the country's major broadcasters. The court's ruling in the copyright infringement case could come as soon as Wednesday; a victory for Aereo could have profound effects on the television business.

At first, I didn't see what the big deal was. I was ambivalent, and briefly even downright dismissive, when a public relations person contacted me in February 2012 and offered an embargoed look at the startup. I worked at The New York Times at the time, and she wanted me to write the very first story about Aereo's launch. "Time is of the essence," she said, because a media briefing was scheduled for Valentine's Day.

I hesitated, but she insisted that I come to the headquarters of Barry Diller's IAC (IACI) for an in-person demonstration of the product, which she called an "online TV platform." Once I was there, I understood. "Surprisingly high-quality signal," I scribbled in my notebook. "Place- and time-shifting!"

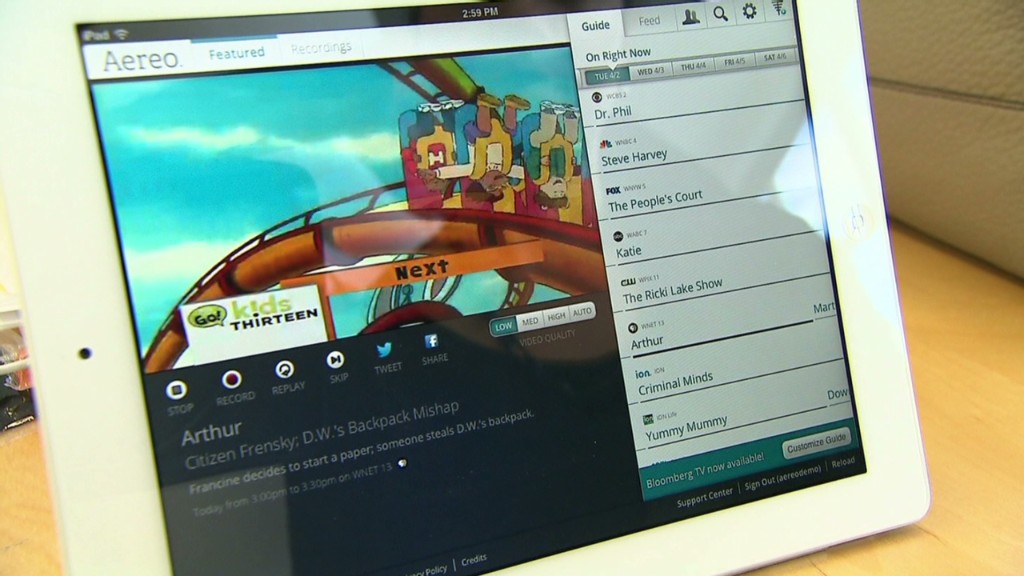

Aereo empowered users to both place-shift broadcast TV (by making it portable via a smart phone) and time-shift it (by including an Internet digital video recorder). The service scoops up public signals of local TV stations and retransmits them to paying subscribers via the Internet. The broadcasters say this amounts to copyright theft on a grand scale; Aereo's backers say it is perfectly legal.

Related: What the heck is Aereo, anyway?

Looking back at my notes from February 2012, the contours of the eventual legal case are evident. "It's an antenna per person," Aereo founder and CEO Chet Kanojia told me. "It's a private exhibition of that content." (The broadcasters say it is a public exhibition, which is a violation of copyright law.)

When we first spoke, Kanojia had already been working on Aereo in stealth for well over a year. Diller, his biggest financial backer, had gotten involved in the summer of 2011.

In an interview for my story, I asked Diller about the potential for legal action against the service. He wouldn't comment directly. But he told me that "when I first heard about this, I thought, 'There must be something wrong here. This can't be.' And I kept scratching at it, as did our lawyers — every lawyer we could find. And I could not find a flaw."

Diller said he didn't expect Aereo to "break the neck of cable-satellite," but that it would present an alternative to a hefty monthly cable bill by providing a small bundle of broadcast TV. That helped to sell my editors on the story.

What intrigued me most about Aereo was the statement it made to broadcasters and cable companies. It was as if Kanojia was saying, "This is the way TV should be -- streamed to any device, anytime, live or on-demand, inside or outside the home, no set-top-box or rabbit ears needed."

Legal action seemed inevitable. During Kanojia's demo, I raised the specter of lawsuits. "We understand that when you try to take something meaningful on, you have to be prepared for challenges," Kanojia said, somewhat sidestepping the question.

Notably, he did say that the company had "talked to everybody, shown them what we're doing" -- he meant local station owners -- and "invited discussion, invited criticism."

When I contacted those local stations and asked them to comment on launch day, they were mum. But they were paying close attention -- they filed two lawsuits against Aereo on the first day of March 2012, two weeks before the service even became available to the public in New York City.

"A plaintiffs' win in this case will ensure the continued availability of this programming to the viewing public," the broadcasters' main Washington lobbying group said when the suits were filed. (Was the group foreshadowing what CBS (CBS), Fox (FOXA) and Univision warned in 2013 -- that their stations might leave the public airwaves if Aereo wins?)

Some observers immediately predicted that the case would make its way to the Supreme Court. At the South by Southwest conference in mid-March 2012, Diller called the suits "absolutely predictable," a case of protectionist behavior by the broadcasters.

"It's going to be a great fight," he said.

And it has been, culminating in a hearing this April at the Supreme Court. Afterward, the normally affable Kanojia declined to say much to the reporters waiting for him on the courthouse steps.

"It's over," he said, as he and his family walked to a waiting car.

Is it? The justices of the Supreme Court will tell us very soon.