The FBI is well aware about the threat to your civil liberties -- especially in an age of unwarranted, mass surveillance of our emails and video calls.

It's why all FBI academy trainees learn about the rise of Nazi Germany and the transformation of law enforcement into a tool of oppression.

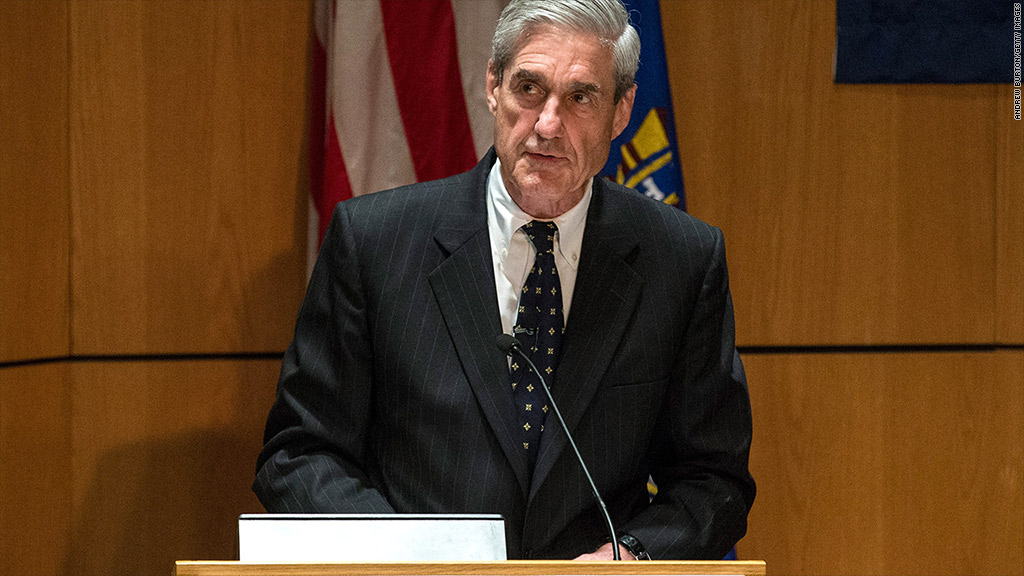

"We send every one of our agents to the Holocaust Museum before they're agents to know and understand what happens when an agency goes rogue," ex-FBI director Robert Mueller explained recently.

Related story: How the NSA can 'turn on' your phone remotely

Agents take a private, guided tour of the museum. Then there's a specialized class that highlights how everyday law enforcement played a key role in Germany's descent into authoritarianism. It wasn't only elite military units, like the infamous Schutzstaffel, or SS.

The presentation includes the slide below, which shows how German police accompanied Nazi bureaucrats as they compiled information about minorities who would later be hunted down and killed. That information was tabulated as punch cards by some of the earliest computers.

"The whole point is to show the transition of police from neutral professionals to perpetrators of this mass genocide," said Marcus Appelbaum, a museum director who coordinates the program.

It's become a valuable gut check for the FBI, which has in recent years had to more delicately juggle "the balance of civil liberties on the one hand, against ... the necessity for thwarting terrorist attacks, cyber attacks and the like," Mueller said at a cybersecurity conference last month in New York City.

His speech was notable, because Mueller called for greater cooperation and information sharing from the private sector -- even as disclosures continue about the extent of vast spying on Americans and foreigners.

It's a forceful, secretive surveillance that major tech companies are currently battling in federal courts. And it's one that makes the FBI trainees' one-day trip to the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. even more relevant, Appelbaum said.

How safe are you? Check out CNNMoney's cybersecurity Flipboard

"It's really the small compromises that will serve to undermine the strengths of our democracy, the rights of the individual," Appelbaum said. "For law enforcement today, the message is: What is it that you can hold on to that will prevent you from committing similar abuses of power?"

Is National Security Agency data collection, the secret court that approves it, and sharing that information with domestic agencies a step in that direction?

Appelbaum wouldn't say. But he said it's exactly what he hopes agents will ask themselves.

A portion of the class at the museum is led by the program's creator, David Friedman, the Anti-Defamation League's director of law enforcement initiatives. He asks the agents point blank: What makes you different? Pointing at the U.S. Constitution isn't enough.

"Look, it's an amazing document. But sometimes there's a separation between the principles expressed and how law enforcement conducts itself at the street level," Friedman said.

Related story: Microsoft fights warrant for customer emails stored overseas

Then he brings up dark moments in American history. Japanese-Americans were sent to World War II internment camps. Civil Rights protestors were beaten by cops. And the FBI's own covert surveillance program, COINTELPRO, targeted athletes, journalists, politicians and grassroots movements for being "subversive."

"We can't afford to think we're different, just because of our DNA or upbringing," Friedman said. "If we're not careful, all of us can slide down that slippery slope."

The FBI isn't alone. Nearly every federal law enforcement agency sends new recruits to the museum. The 90,000 who have been there since 1999 include agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Secret Service and U.S. Marshals, according to the Anti-Defamation League.