The ongoing protests and violence that have occurred over the past several days in Milwaukee are about more than the police killing of Sylville Smith. They are about years of inequity, high unemployment and oppression, the city's Alderman Khalif Rainey said over the weekend.

"[Milwaukee] has become the worst place to live for African-Americans in the entire country," he said at a press conference Saturday.

And when looking at the numbers, it's hard to dispute Rainey's claim.

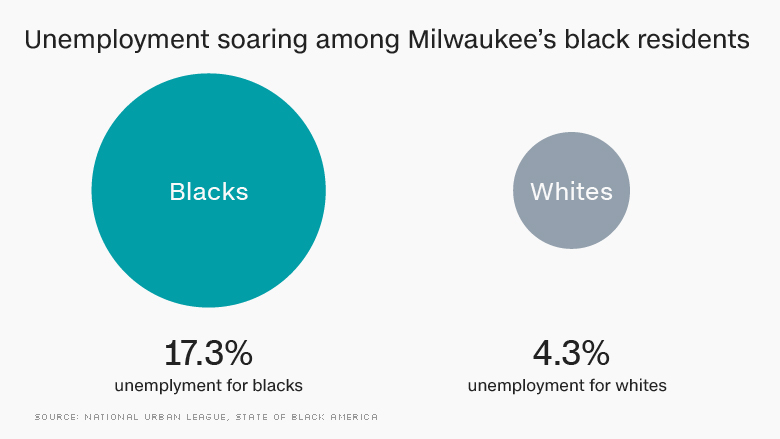

A report from the National Urban League released in May examined economic data for blacks in 70 metro areas and found that Milwaukee has the largest gap in unemployment between blacks and whites in the country and the second biggest income gap.

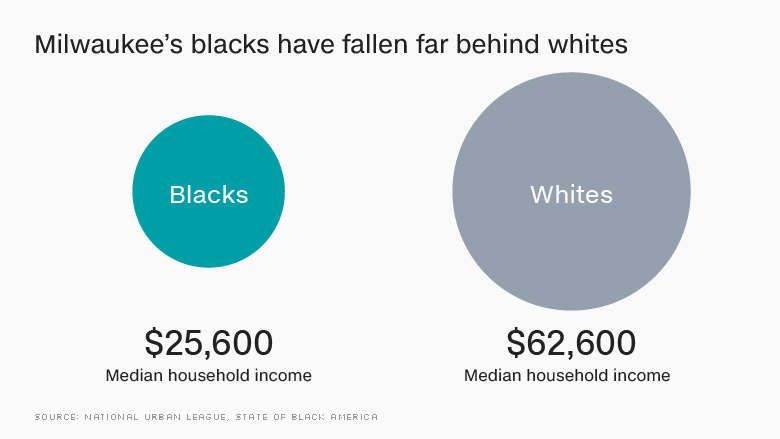

In 2015, 17.3% of blacks in Milwaukee were unemployed compared to 4.3% of whites, the report found. And many blacks in the city were earning much less than whites. According to the report, the median household income for blacks in Milwaukee was $25,600 compared to $62,600 for whites.

"This is not a place where you have a strong, visible African-American middle class," said Peter Koneazny, the litigation director for the Legal Aid Society in Milwaukee. "If you have opportunities, you go elsewhere."

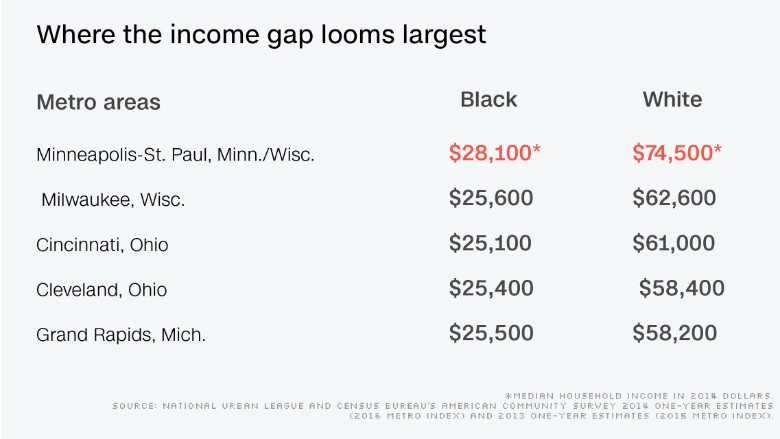

Of course, Milwaukee isn't the only city experiencing such racial and economic disparity. In no metro area were blacks more likely to be employed than whites or make more money, the report found.

Related: Where the biggest inequality gaps are in America

The largest income gap was between black families in the Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, Minnesota, metro area at $28,138 compared to $74,455 for whites. Cincinnati and Cleveland in Ohio and Grand Rapids, Michigan, rounded out the top five cities where the income gap between blacks and whites was largest.

Such economic disparities only add to racial tensions. As Rainey pointed out over the weekend, Milwaukee has been a "powder keg" for potential violence throughout the summer.

"Something has to be done to address these issues," he said. "The black people of Milwaukee are tired; they are tired of living under this oppression, this is their life."

In Milwaukee County, 41% of black men ages 20 to 54 have either been incarcerated or are currently incarcerated, a 2013 study from the Employment and Training Institute at the University of Wisconsin found. And black drivers in the city are seven times more likely to be pulled over by police than whites, according to an analysis conducted by the Milwaukee Wisconsin Journal-Sentinel.

The racial and economic disparities in Milwaukee have been some of the worst in the county for the past 30 to 40 years, said Marc Levine, a public policy professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

In the 1970s, black wealth was created and sustained by manufacturing jobs for companies that sold everything from durable goods to auto parts, Levine said. Then the manufacturing jobs began to disappear.

According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 1990 there were 162,000 manufacturing jobs in the Milwaukee metro area. Today, there are just 123,000. That's almost 40,000 jobs, gone.

The loss of jobs has brought poverty along with it. The poverty rate in the city is nearly 30%, according to the Census Bureau's latest data. But drive 15-minutes to the suburb of Wauwatosa and the poverty rate is just 6%.

According to Levine's research, blacks in the Milwaukee metro area tend to live in these areas of concentrated poverty and few -- just 11%, according to his research -- move out to the suburbs.

When Lillie Wilson and her husband moved into their newly built home in the suburb of Brookfield, Wisconsin in 1971 they were the only black family in the neighborhood. "It was a dangerous era," said Wilson, who is now 79 and runs the local chapter of the NAACP. People wanted to know why the Wilsons were there and how they were able to afford their house, she said.

"I told them I can afford nice things and I want them," Wilson said.

Wilson and her husband both worked at GE, he as a manager and she as an administrator. Today, the Wilsons are still the only black family in their community.

Wilson said the joblessness among blacks has created a "festering resentment" among the area's black residents. That resentment also comes in the form of increased racial tensions among blacks, who are stopped by police for "driving while black, walking while black, doing anything while black" Wilson said. "It was real subtle but now it's rising to the forefront."

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the suburb of Brookfield, Wisconsin, where Lillie Wilson and her husband live.