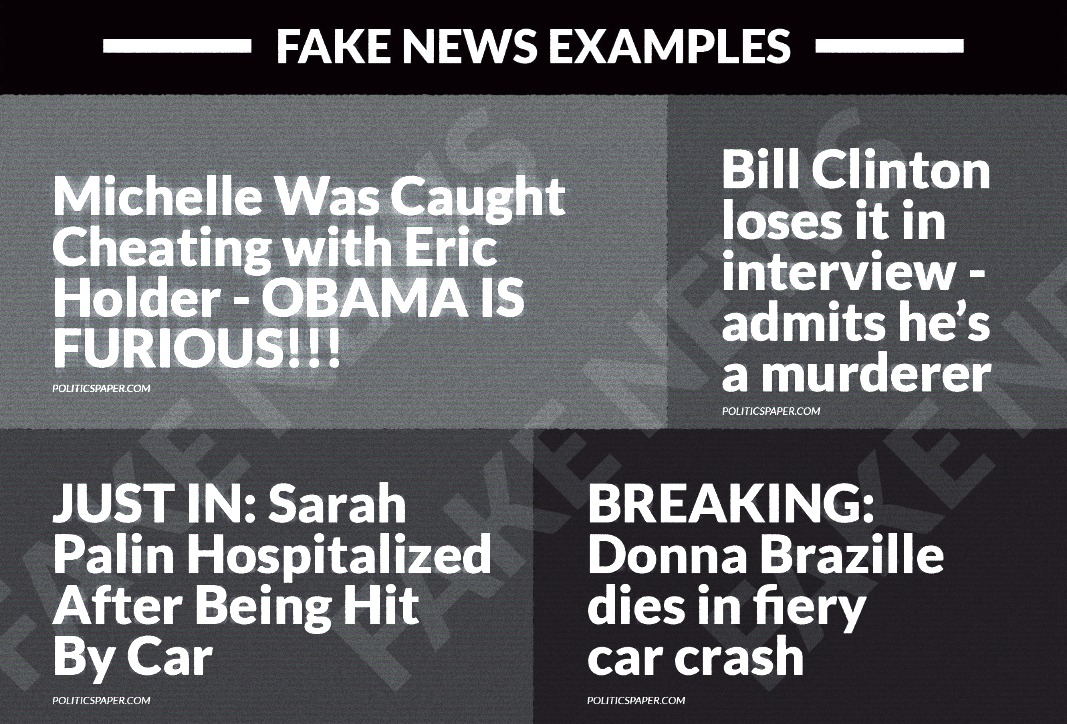

In the weeks following the 2016 presidential election, pundits, politicians and tech titans all sought to figure out whether fake news had affected the outcome.

Hillary Clinton publicly castigated the "guys over in Macedonia who are running these fake news sites," and suggested they may have been working with Russia. The New Yorker reported that President Obama spent a day after Trump's victory talking "almost obsessively" with advisers about the stories coming out of Veles.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was initially more skeptical about Facebook's influence on the election outcome.

He changed his tune, however, and announced a slew of measures designed to control the spread of fake news.

Facebook says it spots fake news accounts by looking for certain patterns of activity — repeated posting of the same content, or a sudden increase in messaging. It is putting warning labels on fake stories in some countries, and the company has also taken steps to undercut the business model of fake news publishers.

In September, Facebook told U.S. congressional investigators that it sold around $100,000 worth of political ads to a so-called Russian troll farm that was targeting American voters during the 2016 election.

Some fake news producers in Veles said they had also paid Facebook for ads, but the company declined to answer questions from CNN on whether it had tracked sales in Macedonia.

Google has also joined in the fight against fake news.

Google declined to share specific data on the number of advertising accounts it has closed in Macedonia. But it said its automated system detects "bad publishers," and is evolving all the time. It also has a dedicated enforcement team that reviews sites.

Three fake news producers in Veles said their Google ad accounts were suspended in recent months, and their Facebook fan pages have been blocked. Several others said they knew people who had experienced the same.

Still, the fake news producers are determined to skirt the controls. One new tactic is buying legit Facebook accounts off young children for €2 ($2.40) before changing the names to sound more American.

Most of the posts will be about Trump, according to Mikhail.

"I'm posting about Hillary, Bernie Sanders maybe sometimes, but I don't get paid enough for that," Mikhail said. ■