The smartest (or the nuttiest) futurist on EarthRay Kurzweil is a legendary inventor with a history of mind-blowing ideas. Now he's onto something even bigger. If he's right, the future will be a lot weirder and brighter than you think.(Fortune Magazine) -- If you went around saying that in a couple of decades we'll have cell-sized, brain-enhancing robots circulating through our bloodstream or that we'll be able to upload a person's consciousness into a computer, people would probably question your sanity. But if you say things like that and you're Ray Kurzweil, you get invited to dinner at Bill Gates' house - twice - so he can pick your brain for insights on the future of technology. The Microsoft chairman calls him a "visionary thinker and futurist." Kurzweil is an inventor whose work in artificial intelligence has dazzled technological sophisticates for four decades. He invented the flatbed scanner, the first true electric piano, and large-vocabulary speech-recognition software; he's launched ten companies and sold five, and has written five books; he has a BS in computer science from MIT and 13 honorary doctorates (but no real one); he's been inducted into the Inventor's Hall of Fame and charges $25,000 every time he gives a speech - 40 times last year.

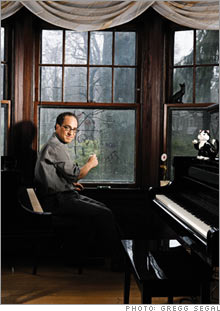

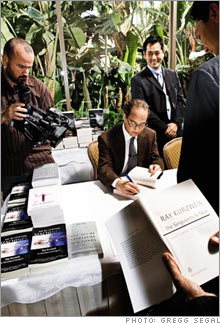

And now, if anything, he's gaining momentum as a cultural force: He has not one but two movies in the works - one a documentary about his career and ideas and the other an adaptation of his recent bestseller, The Singularity Is Near, which he's writing and co-producing (he's talking about a distribution deal with the people who brought you "The Day After Tomorrow"). When Kurzweil isn't giving keynote addresses or reading obscure peer-review journals, he's raising money for his new hedge fund, FatKat (Financial Accelerating Transactions from Kurzweil Adaptive Technologies). He's already attracted a roster of blue-ribbon investors that includes venture capitalist Vinod Khosla, former Microsoft CFO Mike Brown, and former Flextronics-CEO-turned-KKR-partner Michael Marks. Being a hedge fund manager may seem an odd pursuit for an expert in AI, but to Kurzweil it's perfectly natural. The magic that has enabled all his innovations has been the science of pattern recognition - and what is the financial market, he postulates, but a series of patterns? Kurzweil, however, has something bigger on his mind than just making money - after half a lifetime studying trends in technological change, he believes he's found a pattern that allows him to see into the future with a high degree of accuracy. The secret is something he calls the Law of Accelerating Returns, and the basic idea is that the power of technology is expanding at an exponential rate. Mankind is on the cusp of a radically accelerating era of change unlike anything we have ever seen, he says, and almost more extreme than we can imagine. What does that mean? By the time a child born today graduates from college, Kurzweil believes, poverty, disease, and reliance on fossil fuels should be a thing of the past. Speaking of which, don't get him started on global-warming hype. "These slides that Gore puts up are ludicrous," says the man who once delivered a tech conference presentation as a singing computer avatar named Ramona. (That stunt was the inspiration for the 2002 Al Pacino movie "Simone.") "They don't account for anything like the technological progress we're going to experience." He has plenty more ideas that may seem Woody Allen - wacky in a "Sleeper" kind of way (virtual sex as good as or better than the real thing) and occasionally downright disturbing à la "2001: A Space Odyssey" (computers will achieve consciousness in about 20 years). But a number of his predictions have had a funny way of coming true. Back in the 1980s he predicted that a computer would beat the world chess champion in 1998 (it happened in 1997) and that some kind of worldwide computer network would arise and facilitate communication and entertainment (still happening). His current vision goes way, way past the web, of course. But at least give the guy a hearing. "We are the species that goes beyond our potential," he says. "Merging with our technology is the next stage in our evolution." In mid-April, Kurzweil traveled to the Island hotel in Newport Beach, Calif., as one of the featured speakers at a two-day World Innovation Forum. The roster of luminaries included Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen and Vint Cerf, one of the fathers of the Internet, now at Google (Charts, Fortune 500). But Kurzweil was the only one followed around by a team of documentary-film makers. He took the stage wearing a brown houndstooth sports coat and navy checked tie and began toggling through his PowerPoint slides. He's about 5-foot-7, and in regular conversation he tends to speak in a monotone. But he comes alive onstage, mixing in reliable one-liners with his bigger point: Don't underestimate the power of technological change. "Information technologies are doubling in power every year right now," he tells the crowd of 400 or so attendees. "Doubling every year is multiplying by 1,000 in ten years. It's remarkable how scientists miss this basic trend." Kurzweil's crusade, if you will, is to get across that most of us (even scientists) fail to see the world changing exponentially because we are "stuck in the intuitive linear view." To hammer home his point, Kurzweil packs his presentations with charts that show, for instance, supercomputer power doubling consistently over time. He explains that Moore's Law - the number of transistors on a chip will double every two years - is but one excellent example of the Law of Accelerating Returns. One of Kurzweil's favorite illustrations of exponential growth is the Human Genome Project. "It was scheduled to be a 15-year project," he says. "After seven years only 1% of it was done, and the critics said it would be impossible. But if you double from 1% every year over seven years, you get 100%. It was right on schedule." He believes humanity is near that 1% moment in technological growth. By 2027, he predicts, computers will surpass humans in intelligence; by 2045 or so, we will reach the Singularity, a moment when technology is advancing so rapidly that "strictly biological" humans will be unable to comprehend it. Everything will be subject to his Law of Accelerating Returns, Kurzweil says, because "everything is ultimately becoming information technology." As we are able to reverse-engineer and decode our own DNA, for instance, medical technology can be converted to bits and bytes and zoom along at the same fantastic rate. That will enable overlapping revolutions in genetics, nanotechnology, and robotics. Which is how you end up with nanobots living in your brain. Kurzweil, 59, declared his career as an inventor at age 5. He grew up in Queens, New York, one of two children (he has a younger sister named Enid) of Fredric and Hannah Kurzweil, Viennese Jews who fled the Nazis in 1938. His parents encouraged their son's ambition. "Ideas were the religion of our household," he says. "They saw science and technology as the way of the future and a way to make money and not struggle the way they did." Fredric, a composer and conductor, died of heart disease at 58, an event that would have a lasting impact on his son. Kurzweil discovered computers at age 12, and quickly demonstrated an amazing facility with technology. At 14 he wangled a job as the computer programmer at the research department of Head Start, the federal government's early-childhood-development program. While there he wrote software that was later distributed by IBM (Charts, Fortune 500) with its mainframes. At 17 he won an international science contest by building a computer that analyzed the works of Chopin and Beethoven to compose music; that trick landed him on the TV show "I've Got a Secret," hosted by Steve Allen. At MIT he started a company that used a computer to crunch numbers and match high school students with the best college choice; he sold it for $100,000 plus royalties. After graduating from MIT, he founded Kurzweil Computer Products in 1974, and his initial breakthrough came later that year when he created the first optical-character-recognition program capable of reading any font. After he happened to sit next to a blind man on a plane, he decided to apply the technology to building a reading machine for the sight-impaired. To make it work he invented the flatbed scanner and the text-to-speech synthesizer, and introduced a reader in 1976. When his first reader customer - Stevie Wonder - later complained about the limitations of electronic keyboards, Kurzweil used pattern-recognition science to invent the first keyboard that could realistically reproduce the sound of pianos and other orchestra instruments. Thus was born Kurzweil Music Systems. (When his name is recognized today, it's still often as "that keyboard guy.") Kurzweil never left the Boston area after college. He and his wife, Sonya, live in a suburb about 20 minutes west of the city in a house they bought 25 years ago. Both of his children are grown and out of the house - Ethan, 28, is at Harvard Business School and Amy, 20, is at Stanford - so it's just the two of them and 300 or so cat figurines. (Kurzweil says he likes the way cats always seem to be "calmly thinking through their options.") Kurzweil won't say how much he's worth, but he's never had the kind of payday that made so many of his peers centimillionaires or better. He sold Kurzweil Computer Products to Xerox (Charts, Fortune 500) in 1980 for $6.25 million. Kurzweil Music Systems was in bankruptcy when Korean piano maker Young Chang bought it in 1990 for $12 million. Kurzweil Applied Intelligence introduced a series of speech-recognition products and went public in 1993, but was tarnished by an accounting-fraud scandal in 1995. Kurzweil, who was co-CEO, was not implicated. "I was focusing on the technology," he says. "There was this small conspiracy, which was deeply shocking." KAI was sold in 1997 for $53 million. If Kurzweil hasn't made the big score, he's done well enough to keep funding his new ventures. Former Microsoft (Charts, Fortune 500) CFO Brown has invested in a few of Kurzweil's businesses and says he's impressed. "There's a certain smart kind of person who can get all the way from the big picture down to the little kernel and back," he says. "He's extremely adaptive that way. His businesses in my experience have always been well run and successful. He's grown them until they get to be a certain size and typically sold them to somebody who has a bigger distribution network." These days Kurzweil organizes his business interests - including FatKat and Ray & Terry's Longevity Products, which sells supplements - under the umbrella of Kurzweil Technologies. The company takes up all of one floor and half of another in a nondescript office-park building in Wellesley Hills, Mass. In the reception area on the second floor is an antique Ediphone, one of Thomas Edison's dictation machines. On a table filled with plaques noting Kurzweil's achievements is a photo of him receiving the National Medal of Technology from President Clinton. There's a pipe-smoking mannequin with a ribbon that reads I AM AN INVENTOR on its chest. In the basement is a supercomputer processing millions of bits of market-related data. Kurzweil is hoping that FatKat will prove to be as spectacular an achievement as his early inventions, only a lot more lucrative. When describing his approach, he refers to the success of fellow MIT board member and hedge fund manager James Simons of Renaissance Technologies, whose $6 billion fund Medallion has averaged 36% returns annually after fees since 1988 and who, according to the hedge fund trade magazine Alpha, was the highest-paid hedgie last year, with a take-home of $1.7 billion. Kurzweil says he is applying Simons-like quantitative analysis to take advantage of market inefficiencies. And he's confident that, just as he trained computers to recognize patterns in human speech or the sound of a violin, he can do the same with currency fluctuations and stock-ownership trends. The ultimate goal is to create the first fully artificially intelligent quant fund - a black box that can learn to monitor itself and adjust. Although he started the company back in 1999, the fund has only been trading for about a year. How's he doing? Kurzweil won't say, citing SEC rules, nor will his investors. "I view Ray as one of the best pattern-recognition people in the world," says Khosla, when asked why he put money into FatKat. "I am a happy investor in Ray's company. A very happy investor." As respected as Kurzweil is, to some of his peers his ideas have a persistent whiff of the too-good-to-be-true. One intellectual equal who takes exception to Kurzweil's views is Mitch Kapor, the co-founder and former CEO of Lotus Development. In 2002, Kapor made a much publicized $20,000 bet with Kurzweil that a computer would not be able to demonstrate consciousness at a human level by 2029. But his quibbles with Kurzweil run much deeper than that debate. He rejects Kurzweil's theories about the implications of accelerating technology as pseudo-evangelistic bunk. "It's intelligent design for the IQ 140 people," he says. "This proposition that we're heading to this point at which everything is going to be just unimaginably different - it's fundamentally, in my view, driven by a religious impulse. And all of the frantic arm-waving can't obscure that fact for me, no matter what numbers he marshals in favor of it. He's very good at having a lot of curves that point up to the right." Even technologists who take Kurzweil seriously don't necessarily echo his optimism. It was after a conversation with him that Bill Joy wrote an apocalyptic cover story for Wired magazine in 2000 about nanotechnology run amok. Kurzweil, who's always careful to acknowledge the possibility that everything could go haywire, says his outlook is about math, not religion. And he's not planning to go anywhere until he bears witness to humankind's ultimate destiny, even if it takes him forever. Note that by "forever" we mean "forever": The man literally intends not to die. With an acute memory of his father's early death, he's been getting weekly blood tests and intravenous treatments. He also takes pills - lots of pills, more than 200 vitamins, antioxidants, and other supplements every day. It's all part of his effort to "reprogram" his body chemistry and stop growing old. "I've slowed down aging to a crawl," he claims. "By most measures my biological age is about 40, and I have some hormone and nutrient levels of a person in his 30s." Tuesday night in Newport Beach, after his talk at the Innovation Forum, Kurzweil is having dinner at an upscale seafood restaurant with one of his true believers, Peter Diamandis. The 45-year-old Diamandis is best known as the creator of the X Prize, a $10 million bounty for the first privately built, manned rocket launched into space. (Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen's team won in 2004.) He's developing a new X Prize for a 100-mile-a-gallon car, and considering others in cancer research and, with Kurzweil's help, AI. Diamandis says he buys completely into Kurzweil's Law of Accelerating Returns and everything that it implies. "The Singularity, for anyone who stops and thinks about it, is completely obvious," he says. Diamandis, who has an MD, has also been profoundly affected by Kurzweil's 2004 book Fantastic Voyage: Live Long Enough to Live Forever and has adopted Kurzweil's dietary guidelines. Diamandis pulls out a plastic bag of supplement pills and explains he's up to about 30 a day. Kurzweil reaches into his jacket for some of his own supplements. "His pills are bigger than my pills!" says Diamandis. Then, more seriously, he asks Kurzweil if he ever gets nosebleeds from the supplement regimen. Kurzweil doesn't. "I think it might be the memory pills," says Diamandis. The conversation morphs into a debate on why earthlings have been unable to detect extraterrestrial civilizations, because with the billions of star systems out there, surely the Law of Accelerating Returns must have taken root somewhere... It's easy to ridicule a scene like this, and perhaps people will when the movie comes out. (The documentary crew was there.) It's currently unfashionable to be so positive in one's open-mindedness. But remember, Kurzweil has been right before. And frankly, he's delighted we haven't heard from anyone else in the universe yet - it just means we're further up the technology curve than the aliens. "I think it's exciting that we're in the lead," he says, fiddling with his half-eaten ahi tuna. "There's a lot ahead of us." Reporter associates Doris Burke and Telis Demos contributed to this article. From the May 14, 2007 issue

|

Sponsors

| ||||||||||||||||