The return of Ma & Pa BankerFrom the mountains to the prairies, local banks are producing returns that make the multinationals envious. Fortune's Matthew Boyle reviews the balance sheets.(Fortune Magazine) -- Walking through the Mirage Casino in Las Vegas, Kit Cheung could easily be mistaken for a whale on a baccarat bender. But while Cheung is placing a big bet in this town - $25 million, in fact - he's not doing so on the Strip. To see where Cheung has stacked his chips, he ushers me out of the casino and into his white Acura RL, arguably the least flashy of the seven cars he owns. He drives a few blocks west of the Strip and turns onto Spring Mountain Road, the city's rapidly growing Chinatown. Some 50,000 Chinese Americans call Vegas home, and within five years that population should double. Spring Mountain Road has all the amenities - Starbucks and strip clubs - but what it doesn't have yet is a neighborhood bank. (By comparison, Monterey Park, a Chinese-American enclave just east of Los Angeles, has more than 20 small banks.)

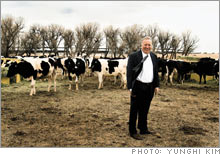

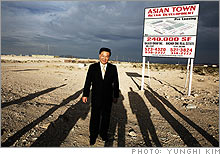

Cheung, 53, points out the strip mall where he plans to open the first branch of his Nevada Pacific Bank later this year (the bank's FDIC charter is expected in the fall). And at the end of 2008, Nevada Pacific intends to establish its headquarters in a 250,000-square-foot retail center dubbed Asian Town. The $70 million development will include the largest Chinese restaurant in Las Vegas - operated by another arm of Cheung's business empire, which also comprises real estate, medical complexes (he's a surgeon by trade) and money management. He leans over and explains how low default rates make Chinese Americans ideal bank customers. "Chinese will pay [off a loan] before they eat," he says. "And Chinese prefer to bank with Chinese. Big banks don't understand our culture." Fueled by industry consolidation and an influx of hedge fund and private-equity capital, community banks like Nevada Pacific, Colorado's New Frontier Bank and New Orleans' First NBC are hot, and not just because of some nostalgic fondness for dog biscuits and lollipops at the teller window. The FDIC began insuring 191 new commercial banks and savings institutions last year, more than double the number in 2002. While megabanks like Bank of America (Charts, Fortune 500) command nearly 60 percent of all industry assets, up from 28 percent in 1985, community banks - commonly defined as banks with less than $1 billion in assets - still make up about 93 percent of the 7,500 banks in this country. The founders of the new community banks relish the psychic income that accrues from helping build local businesses and from being a big fish in a small pond. But the rewards are more tangible than that. Despite the oft-heard arguments for economies of scale, mom-and-pop banks usually outperform the big boys in key metrics like return on assets and net interest margin (the banking equivalent of gross margin). And shareholder returns for publicly traded community banks trounce the Goliaths. "That's why the capital is flowing," says Ed Carpenter, who runs an Irvine, Calif., investment bank that has helped launch more than 700 banks since 1974, including Nevada Pacific. The success of well-run community banks has also made them prime takeover candidates for the Wells Fargos (Charts, Fortune 500) of the world, which often need to acquire smaller banks to keep showing growth. Once content to raise startup capital locally, community bankers like Nashville-based Ron Samuels are staging road shows for private-equity firms in New York and Chicago. (Samuels's bank will cater to Nashville's thriving music scene.) "Hedge funds have been in banks for a long time, but there has been a mindset shift on the part of institutional investors," says Mark Fitzgibbon, director of research at Sandler O'Neill & Partners. Community banks are receiving unprecedented amounts of capital from Wall Streeters like Josiah Hornblower of Resource Financial Institutions Group, which has made 12 investments, totaling nearly $50 million, during the past year. "It's not hard to understand why investors are coming to the sector," says John Eggemeyer, head of Castle Creek, a private-equity firm that has bought stakes in 50 banks over the past 14 years. "Banking is not the most exciting business, but it's a very steady business." Farmer's bank From an observation perch in Colorado's Weld County, Larry Seastrom can see the interest income flowing into his bank, three times a day. It comes in the form of fresh milk from 2,000 cows at a new dairy managed by Aurora, a company that supplies store-brand organic milk for Wal-Mart and Safeway. The cows produce 24,000 gallons of milk per day, and the dairy is not even at full capacity: It will eventually house 3,200 cows, making it one of the nation's largest. Seastrom's New Frontier Bank helped Aurora with leasing and construction, and also lends money to the nearby farms that sell feed to Aurora. "New Frontier is special - they really understand agriculture," says Aurora senior VP of marketing Clark Driftmier. By that he means that there are thousands of loan officers who can look at a house in a suburban cul-de-sac and guess its worth, but it takes a special breed of banker to eyeball Holstein cows and decide whether they are decent collateral for a loan. As a result, good agricultural lenders are a dying breed. Raised in eastern Kansas, Seastrom worked at a string of Colorado banks until 1998, when he gathered six backers and sold stock to 181 Weld County residents, raising $6 million to launch New Frontier (its first headquarters was a trailer). "To this day we still have shareholders whose neighbors say, 'He owns part of the bank,'" says Seastrom. Located in Greeley, New Frontier has become a town hub: The Girl Scouts meet in its community room. Nearly half of the bank's loans support agriculture, an asset-intensive, low-cash-flow, highly cyclical business that bigger banks won't touch. With an eight-year track record of success - American Banker rated New Frontier the ninth most efficiently run bank holding company in the country in the second quarter of 2006 - Seastrom, 51, should expect some bigger banks to start kicking the tires soon. He's not courting offers at the moment, "but if the price is right ... ," he says, his voice trailing off as he ponders the possibility. "Well, maybe that's cold-hearted." Besides, he jokes, with an ownership stake of less than 2 percent of the company, "if we sold, I would need a job the next day." A niche bank Like minutemen operating in the shadow of the redcoats, community bankers have to take their shots where they can - be it by earning the trust of an ethnic community, developing a niche talent, or - as in the case of Ashton Ryan Jr. - by being the first new banker to open in Katrina-ravaged New Orleans. A former partner at Arthur Andersen, where he handled bank audits and helped Louisiana get through the S&L crisis, the 59-year-old saw opportunity where the pinstripe-and-Gucci crowd saw only devastation. Ryan has done his time in big banking, most recently at Bank One (now part of J.P. Morgan Chase (Charts, Fortune 500)). "There's nothing wrong with megabanking - it drives our economy," says Ryan, kicking back in his office at First NBC, which is housed in the Depression-era Canal Bank, a Greek Revival building two blocks north of the French Quarter. "But some people don't like to be a number. They like to be viewed as a person." In the summer of 2005, Ryan decided to launch First NBC. The acquisition of the city's two largest banks - First Commerce (bought by Bank One) and Hibernia (bought by Capital One (Charts, Fortune 500)) - left a huge opening for a bank with a personal touch, he figured. Ryan had barely begun the paperwork when Katrina struck in late August, wiping out, by one estimate, half of the city's 60,000 small businesses. But he was undeterred. In fact, he saw a golden opportunity, since the rebuilding of the city would require fresh capital, and other banks were saddled with bad loans. Plugging into his vast network of local contacts - he's on the board of everything from Junior Achievement to Catholic Charities Archdiocese of New Orleans - Ryan raised $61 million, making First NBC the biggest startup bank in state history. Investors include city royalty like the Manning family - NFL stars Peyton and Eli, brother Cooper, and their father, Archie. Reached in Miami just days before Peyton's victorious Super Bowl debut, Archie Manning said that Ryan's reputation, more than anything else, persuaded him to invest. "He's just a doggone smart man," Manning says. First NBC opened for business in May 2006 and will eventually have more than ten branches in and around the city. It broke even in December, which is unusual for a new bank in its first year of operations. Going forward, Ryan wants to be an acquirer of banks, not the acquired. He also thinks he can replicate the First NBC model in nearby states like Alabama. "I can go anywhere," he says. "I've never had trouble competing with big banks. Bring 'em on." Research Associate Joan L. Levinstein contributed to this article. From the May 14, 2007 issue

|

Sponsors

|