|

Cutting a mortgage charge

|

|

August 13, 1999: 7:29 a.m. ET

Homeowner act aims to make PMI easier to understand and cancel

By Staff Writer Alex Frew McMillan

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - After he bought a condo near Washington in Arlington, Va., Jim Hansen noticed an unusual item on his mortgage statement. He was paying $20 a month for something he didn't understand -- private mortgage insurance.

Hansen asked his mortgage company about it. It turns out that the insurance is required by lenders when a buyer makes a down payment of less than 20 percent on a home. The risk of default is greater, he heard, and the insurance covers the extra liability the holder of the mortgage is taking on.

Hansen put down another $4,000 in equity to take him over the 20 percent threshold. But he then had such a frustrating time canceling his PMI, and finding out about it in the first place, he thought he'd do something about it.

And as a Republican congressman from Utah, Hansen could. He introduced legislation in the House that, with the support of then-Sen. Alfonse D'Amato, R-N.Y., in the other chamber, turned into law in 1998, the Homeowners' Protection Act.

Its provisions went into effect two weeks ago, July 29, a year after the act passed. By requiring mortgage issuers to tell borrowers about PMI and to cancel it at a certain point, the law should make buying a home a little cheaper and easier for people who can't put down a lot of money.

"I'm not against PMI, I think it's very important," Hansen said by cell phone from Utah, where he had just finished a fishing trip with his son. "It does apply and help a lot of people who can't get a conventional loan."

But the act makes it easier for people to see they're paying private mortgage insurance and easier to stop paying it if they don't need it anymore.

What is private mortgage insurance?

PMI first came to the fore in the 1950s, with a push from the Federal National Mortgage Association, or Fannie Mae, and the Federal Home Mortgage Corp., or Freddie Mac. The two largest investors in mortgages started requiring bank lenders, the companies they buy mortgages from, to take PMI out on higher-risk loans.

But those mortgages were few and far between. The pace really picked up in the 1980s, when lenders grew more amenable to issuing what are known as "high loan-to-value" mortgages. The less equity someone puts down, the higher the loan-to-value ratio.

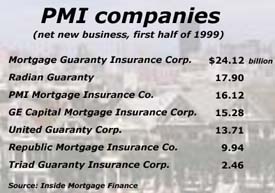

For a larger version of this chart, click here

"It hasn't been long since, if you didn't put down 20 percent, you couldn't get a mortgage," said Darryl Thompson, president and CEO of PMI issuer Triad Guaranty. That's changed. In the 1990s, PMI has helped a million people a year get their foot in the home-buying door. They're typically low- to middle-income people or first-time homeowners.

Last year, a bumper year, 1.5 million families took out PMI and bought a home with a down payment of less than 20 percent.

The mortgage issuers, typically banks, maintain all the contact with the homeowners. But to cover possible defaults, they charge for PMI, which they ship out to a third-party insurer. There are seven companies such as Triad Guaranty, the smallest, that underwrite PMI in the United States.

The average PMI payment is around $20 to $100 a month. The seven companies insured around $175 billion in mortgages last year, Thompson said.

"Twenty years ago, that $175 billion wouldn't have been made. Those people would have been on the outside looking in," he said.

Since inception, around 20 million families have used the insurance to help them buy a home, according to the Mortgage Insurance Companies of America, the PMI trade association. Five million are still paying the insurance.

Why was PMI an issue?

The problem, Hansen felt, is that until recently not many people realized that they were paying PMI or that they can in fact cancel it. As people pay down their mortgages, they approach the 20 percent equity threshold. That's the industry standard showing they're less risky and don't need the insurance.

On a 30-year, 7-percent fixed rate mortgage, for instance, it takes a homeowner that put down 10 percent equity -- in other words, who has a 90 percent loan-to-value ratio -- a little more than eight years to cut the loan-to-value ratio to 80 percent. At that point, the owner could cancel his or her PMI.

But PMI companies don't deal directly with customers. They cancel the insurance only when the mortgage-issuing bank asks them to. Canceling the insurance was discretionary, and the 80 percent threshold was just an industry standard, until this law passed. So banks didn't always cancel it or point out the borrower didn't need to pay. Sometimes canceling was a tricky procedure.

"People were being asked to pay long after they'd finished being a risk," said Kimo Kaloi, a legislative assistant in Hansen's office.

The PMI trade association doesn't track how many people overpaid, though PMI issuers peg it at perhaps 2 percent of their insurance. The promoters of PMI reform tend toward the other extreme -- Kaloi makes a "conservative guess" that 300,000 to 500,000 people continue paying unnecessary PMI.

So what has changed?

In any case, mortgage companies now will be talking a lot more about it, thanks to the Homeowner Protection Act. For all new mortgages, lenders are required to tell customers about PMI when they close on a house. They have to give customers an amortization schedule showing when the PMI will cancel.

The mortgage issuer also has to track the loan-to-value ratio and make the information available. Each year, the mortgage company has to remind customers they can cancel PMI, show them their equity on their original loan, and provide an address and phone number where they can cancel. The notification may be boilerplate, but it's better than nothing.

Homeowners can request that the mortgage company cancel the PMI when they reach an 80 percent loan-to-value ratio on the original price of the house. That's called "borrower cancellation." The request has to be in writing.

Borrower cancellation was always optional, but under the new law it's required and should be an easier, more-standardized process. Homeowners can get an appraisal if they think they've reached 80 percent loan to equity because their house increased in value. Canceling that way is still optional for the bank, not law. The appraisal needs to come from one of the bank's approved appraisers.

Mortgage issuers are required to cancel PMI automatically when the loan-to-value ratio hits 78 percent of the original price. The Mortgage Insurance Companies of America has a Web site that helps with that calculation, though it doesn't point out borrowers can request cancellation at 80 percent.

Homeowners actually can avoid paying PMI by taking out two mortgages at once. The most common financing plan is known as an 80-10-10, or a piggyback loan. A homeowner puts down 10 percent equity, takes a mortgage on 80 percent and then a second mortgage on 10 percent. But because the second mortgage often has a higher rate, it can end up a financial wash compared to paying PMI.

Many people move or refinance before they ever reach the point where they can cancel PMI. But if the value of your house has risen rapidly, which would reduce the loan-to-value ratio, or you've been in a mortgage for a long time, it's worth checking if you're paying unnecessary insurance.

The new law cancels PMI automatically only on mortgages issued after July 29. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac require cancellation on most of their existing policies, but such programs are voluntary. If you hold a mortgage issued before July 29, check. Your mortgage company has to remind you about PMI but it doesn't have to cancel it.

Eight states -- California, Hawaii, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, New York and Texas -- already had their own PMI regulations, which remain in effect if they give more homeowner protection than the federal law.

A hefty dose of the act is awareness. Private mortgage insurance is esoteric and hardly the most significant factor in the biggest purchase most people make in their lives. But why pay $1,200 a year if you don't have to anymore?

Before the debate over the act, not many people were even aware PMI existed. "It's a wake up call," said Lee Verstandig, senior vice president of government affairs for the National Association of Realtors. "Take a look and see where you are in your loan."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|