|

An age of paper wealth

|

|

December 27, 1999: 12:03 p.m. ET

Modern millionaires are a dime a dozen, but will their riches endure?

By Staff Writer Alex Frew McMillan

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - Who wants to be a millionaire? We all do, it seems.

And thanks to the phenomenal wealth created this century, this decade, even this year, many of us have. Lots of people have become wealthy beyond their wildest dreams.

When you look at net worth, the number of millionaires has more than doubled since the start of the ‘90s, hitting 7.9 million in 1998, according to Spectrem Group, a San Francisco-based market-research company.

There are 3.3 million households with more than $1 million of purely investable assets, Spectrem found in a 1999 study. That compares with 1.6 million in 1990. There are also 590,000 households that fit the "pentamillionaire” profile, meaning they have a net worth of more than $5 million.

Two trillion dollars a year

Much of that money has come from the stock market. That means it’s largely paper wealth. It could prove ephemeral if the bubble eventually bursts.

And many market watchers warn -- and perhaps secretly hope -- that the dot.com days of IPO wealth will come to an end sometime. Many people ask: What will your Internet millionaires be worth then?

Not much is the answer, but of course no one knows when the question will come. At the end of 1999, there is no doubt that U.S. investors are high on the hog. The data can be presented any number of ways. The most striking figure might be that in the last five years, from November 1994 to November 1999, the value of the U.S. markets has increased by $10 trillion.

Ten trillion dollars in five years. Two trillion dollars a year, on average. "This is unprecedented, the money pouring in,” said Yale Hirsch, who compiled that statistic and edits the Stock Trader’s Almanac at the Hirsch Organization. The American versions of capitalism, democracy and liberty -- without war to soften the economy -- have created phenomenal personal wealth.

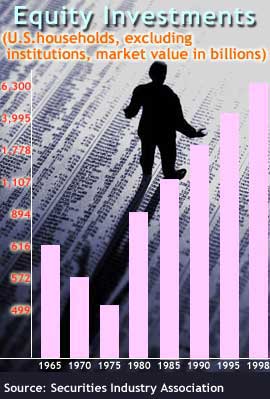

Just over 40 percent of the stock is held by individuals, who own $6.3 trillion in U.S. equities, compared with $9.1 trillion held by institutions. So presumably 40 percent of that $10 trillion in stock gains has found its way directly into individual investors’ pockets.

And the rest of those gains will, too -- since, as one chief investment officer pointed out, individuals are the beneficiaries of the institutional investments in pension funds and the like.

Yes, there are around 30 ethnic conflicts worldwide at any one time, Hirsch conceded. But tell that to Internet millionaires and see if they care. "All the wealth that is created, it’s really a fantastic time,” he said.

Gains not felt by half the population

The words that people use to describe the wealth are as flimsy as the paper it’s printed on. Phenomenal. Fantastic. It’s almost as if people can’t believe the numbers they read. Could the wealth evaporate as quickly as it has come? Is all well in paradise?

Yes and no. The wealth has not been spread as broadly as it might have been. The number of U.S. investors that hold equities has increased substantially, up 86 percent since 1983 to 78.7 million, according to the Securities Industry Association. But more than half the households in the United States own no stock at all. For those people, the stock gains are truly mirages, something they can see but cannot grasp.

Similarly, the Consumer Federation of America figures that one half of American households have amassed less than $1,000 in net financial assets. Add Americans’ home equity and their cars into the equation, and the middle, or median, American household is worth just under $36,000 all told. Which means half have less than that, CFA executive director Stephen Brobeck pointed out.

So most of the wealth hasn’t trickled down very far. "The last two years, all incomes are up, unemployment is low, so the society as a whole has benefited,” he said. "But about a third [of the population] have benefited enormously, both by having great jobs and the ability to buy stock in one way or another.”

Where is the wealth? Stock ownership has spread over the last 15 years or so, Brobeck concedes, but even the typical investor doesn’t own that much of it. The poor have done better, he said. But a familiar refrain always plays in the background -- the rich are getting richer. At the top of course, are the computer and Internet stock-owning "aristocracy.”

Our idea of wealth has changed

And what is wealth? Internet wealth is real for those who have it, according to Lester Thurow, a professor of economics and management at MIT’s Sloan School of Management and author of the book Building Wealth. They can buy the houses, the Rembrandts, whatever they want, he said.

"It isn’t paper wealth for the individual, because you can convert it,” Thurow said. "It’s paper wealth for the society.”

He pointed out that for every Internet retailer that gains, a conventional retailer has to lose. And you can’t use stock to build anything, he said. Of course companies do acquire assets with their stock. But from an economic point of view there is a corresponding cost. "If I sell a share of stock, someone else has to buy it,” Thurow said.

There are benefits to the "wealth” society from the technology boom, of course. Diseases are now curable that once could not be cured. People are able to communicate more quickly and stay in touch over longer distances. Anything that allows people to do new things in new ways is a gain, as opposed to just a new way of doing an old thing, like Internet retail. Buy a car online, "and you still end up with the same car,” Thurow said.

So is this really the century of wealth? "It has not been a century of wealth creation,” he said. "It has been two bursts of wealth creation.”

Over and over, academics and business experts draw comparisons between the technology boom at the end of the 20th Century and the industrial boom at the end of the 19th Century. In a period of rapid technological change, you get rapid wealth creation.

Billions, not millions

The wealth has come so quickly that the very idea of how we think of wealth has changed. Thurow doesn’t think measuring the number of millionaires is that meaningful anymore, there are so many of them. "If you have a million dollars, you’re not very wealthy anymore,” he said. Instead, he measures the number of billionaires.

There were 237 billionaires created in the 1990s in the United States, he said. There were 13 created in the 1980s. And then a big gap. None in the ‘70s, ‘60s or ‘50s. In fact, you have to look for Henry Ford in the 1920s for the next-most-recent billionaire. Then you have to go back to the turn of the last century, when dozens were created.

That last turn of the century produced long-lasting wealth for the men who created it and the companies they created. Of the Fortune 500 as of 1996, 240 -- or almost half -- were created between the 1880s and the 1920s, according to Alfred Chandler, professor emeritus of Harvard Business School and a business historian. By contrast, less than 20 percent have been created since 1950.

The Rockefellers, Carnegies and Vanderbilts were in fact much wealthier than their counterparts today, when you adjust for inflation or look at their wealth in terms of national output, Thurow pointed out. John D. Rockefeller’s riches were significant enough that he controlled close to a tenth of the gross national product.

But that’s just a question of degree. For practical purposes, "they were wealthy in exactly the same way that (Microsoft chairman) Bill Gates is wealthy,” Thurow said.

What the Internet and computer technology has created at this turn of the century, oil, electricity and the combustion engine created at the turn of the last. "New scientific breakthroughs allow you to do these things,” Thurow said.

Is this a second Gilded Age?

That will end. The Industrial Age burst lasted for around 25 years. This current burst started in the 1980s and has intensified since the boom of the Internet in 1995. The technologies eventually mature, competition intensifies, and the revolutionary change stops. And people don’t get rich as quickly.

"In normal times, it’s hard to get fantastically rich quickly,” Thurow said. "People in the 1950s were just as smart, worked just as hard, wanted to get rich as much, but there were no billionaires.” In a way, it is a positive step. When rapid change is occurring, mediocre businesses can prosper if they are producing new technologies, Thurow said. In mature times, you have to be good.

But at this point in the Internet boom, wealth is created ever more quickly. "Our time frame has accordioned,” said Frank Fernandez, chief economist of the Securities Industry Association. "Time is contracting.” Riches can be made overnight, and many people expect that to happen to them.

Socially, that bothers Fernandez, who calls this another Gilded Age. "Has this changed the psyche of the country? I think it has, sometimes not for the better,” he said. In a Gilded Age, social mores matter for little. Information is more important than thought or thoughtful reflection, he said. "There’s more of a superficiality, the get-rich-quick mentality, give it to me now.”

And, Thurow pointed out, most people reading about the success stories forget that between eight and nine of every 10 businesses that venture capitalists fund go out of business in their first five years. "Somehow, we’ve got the idea that it’s quick and easy,” Thurow frets. Those that succeed work hard.

The misperception can have a bad effect on motivation and can also encourage people to launch businesses without the right preparation. "They all go broke and lose their money,” Thurow said almost gleefully.

Mature competition will come

The successful companies comprise a very small base, as Chandler, the business historian, rammed home with the small number of Fortune 500 companies created in the second half of the century. In 1999, 65 stocks have accounted for 99 percent of the gains, through October, according to the SIA.

Will the information, technology and dot-coms meet a similar crash, like the biotechnology speculative boom in the 1980s? With biotech, speculation that companies were developing cures for numerous diseases came crashing to an end when investors became impatient while the companies built factories and tried to develop the drugs.

"I don’t think the Internet can continue [its growth]” Chandler said, because it revolves around information many people can provide. "But I don’t know,” he admitted.

He worries that the U.S. technology companies will face a threat from the nine large Japanese consumer-electronics or computer companies that have dominated industry there since their founding, for most of them before World War I. They will make the hardware that combines computers and consumer electronics, Chandler said, "and software is no good without the hardware.”

Five -- Fujitsu, NEC, Toshiba, Hitachi and Mitsubishi Electronic -- are computer companies that also produce consumer electronics such as televisions. Four -- Matushita, Sony, Sanyo and Sharp -- are consumer electronics companies that also make computers and other industrial products.

They each have hundreds of plants around the world and the global distribution networks to sell a blended computer-television. They have "concentrated technological power,” Chandler said, "that’s going to have a great impact.” They could pose significant competitors for American hardware and software manufacturers, he thinks.

There was also great speculation that the industrial companies of the Rockefeller age also couldn’t sustain their gains, Chandler said. For instance, Chandler’s great-grandfather Henry Varnum Poor, founder of Standard & Poor’s, at first would not compile information on the industrial companies he thought were "fly by night.” That miscalculation fueled the founding of Moody’s, Chandler said.

The best industrial companies proved longer lived, though their growth slowed after the Industrial Age boom. "You’ve got many of the same uncertainties now,” Chandler said. "There’s a lot of parallels in the high-tech industries, particularly in the electronics-based industries, to what was happening at the turn of the century.”

The companies that got there first made great wealth for their stockholders. "There was this same feeling, that this doesn’t feel quite right,” Chandler said. And then it leveled off.

Thanks to Social Security, he expects a crash will not lead to a depression. But people with retirement holdings in the market, particularly the middle class, would notice the effect more directly.

These times of rapid technological growth, and rapid wealth creation, can’t last forever, Chandler and others maintain. Some think the easy money has already been made. "Obviously competition will come,” Chandler said.

That’s when everyone finds out exactly how much paper wealth is here to stay.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|