|

The artful investor

|

|

May 19, 2000: 11:06 a.m. ET

Ultimate buy-and-hold strategy works -- if masterpieces treated like stocks

By Tatiana D. Helenius

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - Art as an investment can bring pleasure and acclaim; it even can deliver substantial returns. But experts warn that novice investors, especially those with an untrained eye, should tread carefully when placing their bets.

"The likelihood that an investor might be able to randomly pick the next Picasso -- that's a lot like buying a lottery ticket and hoping to win big," said Michael Moses, an author and associate professor at New York University's Stern School of Business, who maintains the art market research site ArtInvesting.com. "You have no real data here on what the average return is from a random purchase of art."

Then again, those returns can be amazing.

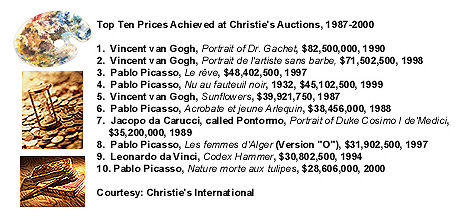

In 1990, for instance, $82.5 million changed hands in one of the biggest deals of the decade. In 1990, for instance, $82.5 million changed hands in one of the biggest deals of the decade.

The buyer walked away with a paint-daubed canvas, not much larger than a briefcase. It was entitled Portrait of Dr. Gachet, an original work by famed artist Vincent Van Gogh, and it remains one of the most valuable art properties in the world.

Due diligence

The best way to get started, says Lorayne Fiorillo, senior vice president, investments, at Prudential Securities, is to look at a potential art investment the same way you look at other investments.

"How many people are going to  drop a substantial bit of money into a mutual fund without reading the prospectus?," Fiorillo asked. "Not many. Not if they are prudent investors. You should approach art in the same way. Look at established names as blue chips and unknowns as penny stocks -- and treat your expectations about your rate of returns the same way." drop a substantial bit of money into a mutual fund without reading the prospectus?," Fiorillo asked. "Not many. Not if they are prudent investors. You should approach art in the same way. Look at established names as blue chips and unknowns as penny stocks -- and treat your expectations about your rate of returns the same way."

"Also keep in mind that even with an established artist, past performance is no guarantee of future returns," she added.

A good way to start researching a specific area, or artist, is to "go to auctions, look at catalogs and prices realized, ask a reputable dealer for their advice," said D.J. Dougherty, director of Park South Gallery in New York City.

"The art market is not as open as the stock market, and information is not always as easily available as, say, stock quotes," he said. "So public information, such as prices realized at auction, is something to start with."

Moses added that an investor also could go to any one of 100,000 galleries and randomly choose any "new" work with his eyes closed. Moses added that an investor also could go to any one of 100,000 galleries and randomly choose any "new" work with his eyes closed.

"The purchase price is well documented in this case," he said. "But as to what the return on that work will be, or what it has been in the past, there may be no verifiable information available. The only data worth talking about is public information on repeat sales of art. It's the only trustworthy data available."

Apart from visiting galleries, museums and consulting dealers, potential investors also can research the market, browse offerings, or find knowledgeable sources for inquiries at auction sites such as Christies.com, Sothebys.com or international art journal The Art Newspaper.com.

Art Market Research and ArtPrice.com provide interactive art market information, while sites like the Appraisers Association of America provide access to appraisers with expertise on a variety of art objects, from paintings to vintage posters, to ceramics or sculpture.

The Diebenkorn affair

Shopping online for a newly discovered Basquiat? Sure, the "wired" auction is a convenient way to acquire an art pick, but when it comes to the goods, are Web-based auctions failing to deliver?

Earlier this month a seller on auction site eBay using the handle "golfpoorly" offered a painting reputedly by contemporary artist Richard Diebenkorn.

Although no guarantee was made that the painting actually was by Diebenkorn, whose 1959 Horizon-Ocean View sold for $3.9 million in 1998, the seller included a close-up of the painting, which showed what looked to be the artist's signature, RD52.

The starting bid of 25 cents eventually escalated to an offer of $135,805 from Dutch collector Rob Keereweer. The starting bid of 25 cents eventually escalated to an offer of $135,805 from Dutch collector Rob Keereweer.

"I decided to take the risk because the pictures of the painting looked good," said Keereweer in an interview with CNNfn. "The story of the seller sounded OK and the answers to the questions of some of the bidders sounded OK."

However, Keereweer said, "The seller and I agree to bring in an expert opinion before finalizing the deal."

David Redden, executive vice president at staid auction house Sotheby's, was unamused by the online antics of either buyer or seller.† The transaction† "seems totally bizarre," he told CNNfn's Moneyline. "The art market is not a lottery."

Hear more of what Redden had to say by clicking on: [137KB WAV] or [137KB AIFF].

However, the deal later soured when eBay determined that the seller had made at least one $4,500 bid on his own painting, a practice known as "shilling," which generally drives the price up on items offered for auction. The seller later was barred by eBay.

Fabulous fakes and other risky business

There are several risks specific to art collecting that investors should be aware of.

In her book "Financial Fitness in 45 Days," Fiorillo cites an example from her own experience. A savvy investor and financial advisor, she found herself the owner of a "faux" Miro.

Fiorillo, having retitled the work a tongue-in-cheek Fake Miro in Lovely Frame, did some research on art fakes. Mirů, she found, is one of the most frequently copied artists in the world, along with Dali and Rembrandt. Fiorillo, having retitled the work a tongue-in-cheek Fake Miro in Lovely Frame, did some research on art fakes. Mirů, she found, is one of the most frequently copied artists in the world, along with Dali and Rembrandt.

"It [art forgery] is the most marvelous crime," writes former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Thomas Hoving in his "False Impressions: The Hunt for Big-Time Art Fakes." "Lots of money to be made without penalty."

So how does an investor protect against being swindled? As with any investment, there are no unshakeable guarantees. But investors might feel more comfortable when they make purchases that have been thoroughly researched by experts in the field, said Marc Porter, international business director of 19th and 20th century art for Christie's.

Provenance, or the history of a specific art object, must be established through extensive research before many art objects are even offered through reputable auction houses.

"Let's take, for example, a piece of 18th century silver from a Philadelphia estate," said Porter. "Before that item is even put on offer, our silver experts will go to the recorder of wills in Philadelphia and look at inventories for the 18th century to see where that particular piece of silver has been, where it originated. This value-added service is what gives clients confidence that they are acquiring a piece with an established provenance, that the item is authentic."

Buy, sell...or hold?

Illiquidity, insurance and maintenance costs, lack of demand, forgeries -- these all are risks associated with art as an investment.

In addition, Moses said, substantial art purchases also entail opportunity cost for the investor, as significant amounts of money are lodged in a single asset class.

"There is really no such thing as an art mutual fund," he noted. "Mutual funds can only hold financial assets, and, for individuals who does want to diversify, they can't really diversify by holding a piece of a Picasso. You can buy a share in a mutual fund, you can buy two shares of Yahoo!, for instance. You can't buy a square inch of a particular painting."

Still, returns on art can be substantial.

Moses takes the example of Picasso's Le rÍve. The piece was purchased in 1941 for $7,000. The painting brought in more than $48 million at a Christie's auction in November 1997.

"This gave the holder an annualized return of 17.1 percent," Moses said. "A randomly selected subset of S&P 500 stocks held for the same period would have yielded, in general, an annualized return of approximately 8 percent."

Over that same time horizon, the S&P 500 index yielded 12.8 percent. Long-term bonds held over the same time frame would have resulted in an annualized return of about 5.2 percent.

William N. Goetzmann, a Yale School of Management professor with an extensive background in both art and finance, has made studies that suggest overall returns on art -- given appreciation in value and holding period -- generally fall somewhere above returns on bonds, but somewhere below profits made in stocks.

In his study, Accounting for Taste, Goetzmann looks at returns in the art market from 1715 through 1986, using resale figures gleaned from historical auction documents. He compared simulated portfolios of art properties against returns from stocks and bonds, allowing for inflation in each case. "Comfortingly, returns for art were definitely well into the double digits," he said.

Overall, Goetzmann also found that percentage variations in the art market tended to be greater than those for stocks. "Art is a very risky asset, no question," he  said. In looking at historical returns, "We see roughly a 50 percent-per-year variation in the art market, while in the stock market, most companies might ordinarily be expected to see a 30 to 40 percent variation per year -- they might be up or down 30 to 40 percent, typically." said. In looking at historical returns, "We see roughly a 50 percent-per-year variation in the art market, while in the stock market, most companies might ordinarily be expected to see a 30 to 40 percent variation per year -- they might be up or down 30 to 40 percent, typically."

Of course, says Goetzmann, in volatile markets, stocks can decline or advance more spectacularly. But then, so does the demand for art, "although demand in the art market lags financial market performance by one to two years. The art market is really driven by gains in the financial markets."

The risk-versus-reward relationship is especially relevant in art investment, says Goetzmann.

"Probably the best way to view art investments is to think of a portfolio of paintings the same way you'd think about the volatility of Internet stocks," he said. "The reward is there, but so is the risk. Investors have to decide what level of risk they are comfortable with."

* Disclaimer

|

|

|

|

|

|

CNNfn: investing

|

Note: Pages will open in a new browser window

External sites are not endorsed by CNNmoney

|

|

|

|

|

|