|

Day trading loses shine

|

|

August 9, 2000: 6:33 a.m. ET

Novices learn that going one-on-one with Wall St. isn't easy money anymore

By Staff Writer Alex Frew McMillan

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - Almost a year ago, Don Rogers figured that a new world of riches awaited him. That was assuming he could get the day-trading techniques that he was learning down.

Rogers also worried the world of rapid-fire trades would prove too tough to master. "I feel like I've fallen off the cliff into the abyss," he said as he started his $5,000 course at Montvale, N.J.-based All-Tech Investment Group Inc.

It was too tough. Rogers has spent nine months trying his hand at "intense momentum trades" out of his home in Greenville, S.C. Unsuccessfully.

"I never did make any money out of that," Rogers, now 61, admits. "I'm just not able to make it work. It's harder than it looks."

Tech stock volumes take a dive

It seems many dilettante day traders share his disappointment. Money and confidence flowed in 1999 as Nasdaq ran up 85.6 percent. That carried over into the first quarter. It seems many dilettante day traders share his disappointment. Money and confidence flowed in 1999 as Nasdaq ran up 85.6 percent. That carried over into the first quarter.

But Nasdaq peaked in March. After a tech-stock meltdown in April, investing has proved to be hard work once again in the 21st Century.

With their reliance on margin accounts and their fondness for the most risky stocks, day traders such as Rogers have suffered greatly in the downturn this year. Nasdaq closed Tuesday down 5.4 percent for the year.

Where are the traders of yesteryear?

Trading volume in Internet stocks, averaging 260 million shares a day, is down 17 percent in August, compared with the previous month. There was an even bigger drop in Internet-stock volume, 33 percent, between the record volume month of April and May.

That's according to a report by Credit Suisse First Boston analyst Jim Marks, who uses Internet stock volumes as a proxy for online trading. A few hundred thousand of the most-active online traders account for the majority of online volume. If they aren't all exactly day traders, who sell positions within minutes and certainly by day's end, they come close.

Marks has explained that trading spiked in the April downturn as investors scurried to shed positions. Though volumes rallied in June, they're down again now, and well below where they started the year.

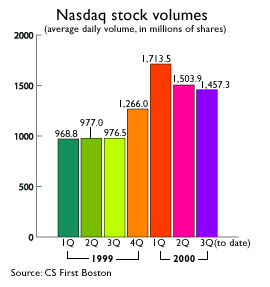

Nasdaq volumes, which declined 12 percent for the second quarter as a whole despite April, according to Marks' report, are down 3 percent so far in the third quarter. And they're nowhere near the feverish pitch of the start of the year. Day traders also favor Nasdaq stocks.

Wall Streeters attribute the volume decline partly to day traders being beaten out of the market, and partly to summer doldrums. But Wall Streeters tend to dislike day traders, and it is hard to say exactly how many have left for good.

No decline in the hard core pros

The most-reliable stats come from the Electronic Traders Association, the day-trading trade group. It reports that the number of full-time, professional day traders in offices around the country has not changed. Regulators, who don't track day traders, do not contest the claim.

The ranks of full-time day traders stand firm at 6,000 to 8,000, according to ETA President Jim Lee, who is also president of day-trading brokerage Momentum Securities, now owned by Tradescape.com.

"There's this huge misconception in the marketplace that, in the selloff, this phenomenon goes away. It's just not true at all," Lee said. "Professional traders know how to trade in both up and down markets." Volatility is all a trader asks for, Lee said.

In fact, at Momentum Securities, Lee says traders were trading more and making more money while the tech stocks were crashing. They short stocks in bad markets.

According to Momentum's databases, the average number of trades increased 19.5 percent in April, over March, when Nasdaq peaked. Average profitability per trader per day, net after commissions and fees, went up 35.5 percent in April, to $5,544.

So who bore the brunt of the tech-stock crash and dot.com carnage? Lee says very active online traders, or "day-trader lights."

"There's two reasons for that. No. 1, there's a tendency to hold positions. And [No. 2] they have a tendency to have leveraged positions, and very limited short-selling characteristics."

An industry tries to clean up its act

Besides Rogers, CNNfn.com tracked day trader and former Merrill Lynch trainee Dan Ripoll for a day last August. Ripoll made close to $15,000 in a day's trading, while his friend Luis Sierra lost $700.

Ripoll and Sierra are still day trading out of Ripoll's house in Miami. They use direct-access brokerage Tradescape.com's remote-access software.

Ripoll says he lost more than $1 million in his investment account during the downturn earlier this year. But day trading has continued to be profitable, he says. "There's just as much money to be made out there," he said. If the market is weak, he goes short," he added.

"If people have stopped they might be people with Ameritrade accounts who called themselves day traders," Ripoll said. "But I don't know anybody who does what I've done that has stopped." "If people have stopped they might be people with Ameritrade accounts who called themselves day traders," Ripoll said. "But I don't know anybody who does what I've done that has stopped."

"It's not easy but you can still make a little bit," Sierra agreed. Both of them now mainly trade initial public offerings immediately after they open, looking for them to run up.

The IPO market lacks some of the massive first-day "pops" it saw last year. But Ripoll said that is good for day traders, who typically can't buy pre-IPO stock and instead trade in the aftermarket.

"If they open at $200, there's no money to be made," Ripoll said. "But a new issue like Click Commerce (CKCM: Research, Estimates) opened at 14 and rose to a first-day high of 20. Good money if you catch it right," he said.

Regulators ease their pressure

Traders like Ripoll claim they make day trading work. Indeed, regulators, who always said they weren't trying to run experienced traders out of business, aren't as concerned about day trading as they were last year. Back then, several of them painted the bete a very dark shade of noir indeed.

After glowing initial press coverage of day trading, some day-trading companies made wild claims about profitability and risk levels, according to Marc Beauchamp, a spokesman for the North American Securities Administrators Association.

Then the industry came under regulatory and media fire, particularly in light of Mark Barton's rampage in two Atlanta day-trading offices. After the bad publicity and regulatory pressure, there seems to be more of a balance, with prospective traders more aware of the risks, Beauchamp said.

Firms "that want to stay in business have been under the regulatory microscope, and they're very careful now about the claims they make," he said. "They've cleaned up their Web sites and toned down their rhetoric."

According to Beauchamp, the truth is that "day trading has always been tough and risky. And since April it's gotten tougher."

Rules that are there to be broken

The truth is also that people like Rogers, a novice day trader, bore the brunt of the bad markets. Last August, he said he was setting aside $50,000 to trade with. He added that he couldn't really afford to lose more than $20,000, though, or his wife would kick him "out of the house."

Rogers still has a roof over his head. His wife has stuck around. But he has lost more than his limit.

In fact, he lost more than his limit on one trade, a disastrous 1,000-share decision to go long on WorldCom (WCOM: Research, Estimates). He bought it. It went south. He held it, violating the day trader's cardinal rule to cut your losses quick. It went south some more.

"I should have taken my loss, and so that was a really dumb thing to do," Rogers admitted. But he couldn't sell right away - because, he says, many other traders were selling ahead of him. Then his trade got cancelled or "timed out."

Even so, it was very rare for him to hold a stock overnight. He broke the rule, confident WorldCom would come back.

In all, it declined from 50-15/16 to a closing price of 35-15/16 on Tuesday as he chased it down. Rogers sold 300 of the shares into some strength at 47. He still holds the other 700, hoping WorldCom will rally. But on paper, that one trade has cost him $24,000, plus commission.

Cutting gains short and compounding losses

Academics who have studied day trading say Rogers' experience highlights the perils of the profession. In theory, cutting your losses short and taking quick gains works beautifully. But practice is often far from perfect.

Ronald Johnson, an investment consultant in Palm Harbor, Fla., analyzed day trading in a report for state regulators. He concluded that day traders cut their gains short by selling quickly.

They try and cut their losses quickly. But because they only take small profits on good trades, and they trade in big blocks of shares, one wrong decision of a few points is cataclysmic, wiping out all their gains and then some, Johnson found. Once the capital is lost, it takes many, many, many profitable small trades to rebound, Johnson said. It may not even be possible, he found.

Mental errors cost him dear

That's what happened to Rogers. "You realize you did two or three really stupid things that cost you significantly," he said.

When he bought WorldCom, Rogers says he was really trying to buy 3Com (COMS: Research, Estimates) while it spun off Palm (PALM: Research, Estimates). He got confused, he said, because he had been researching two similarly named stocks at the same time.

If that sounds strange, it's worth pointing out that many day traders trade stocks on even less -- without knowing what they are spinning off, or what the company does, or even the company's name. A ticker moving in the right direction is enough.

Rogers paid for his error. He made another mistake one day when he shut his computer down without checking his positions. He accidentally took a position of 1,000 shares "home," he left a position open that he had intended to sell. He thinks it was Ameritrade (AMTD: Research, Estimates) but isn't sure. The next day it gapped lower.

Rogers is still confident he can read patterns in stock movements. But he admits he has been wrong about hunches, too. People who have studied electronic trading say that's the point - active traders tend to attribute their good trades to their expertise and their bad trades to bad luck.

Rogers is doubly unlucky, and close to giving up on the whole day-trading idea. In retrospect, he says he would have been better off just investing in bellwether tech stocks like Cisco Systems (CSCO: Research, Estimates). They ran up last year. But he was in class, learning to day trade.

"I really blew the opportunity back in the bull market to really make some money because I was so determined to learn this other technique, which it was so hard to master," Rogers said.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|