|

High Court declines Microsoft review

|

|

September 26, 2000: 4:35 p.m. ET

Supreme Court sends antitrust case to lower Appeals Court

By Staff Writer David Kleinbard

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - In a victory for Microsoft Corp., the Supreme Court Tuesday declined to consider the government's bid to break up the software giant, choosing instead to send the case to a lower court.

In an 8-to-1 decision, the justices rejected a motion by U.S. District Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson to have the case sent directly to the High Court, bypassing the U.S. Court of Appeals. The Justice Department and the 19 states suing Microsoft advocated bypassing the Appeals Court, arguing it would resolve the case more quickly.

[Click here to read the entire Supreme Court decision in Adobe format]

The decision is widely regarded as a procedural win for Microsoft because the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia has ruled in the Redmond, Wash.-based software maker's favor in prior antitrust matters with the government. However, the circumstances in those appearances before the Appeals Court were different than in the current sweeping antitrust case against Microsoft.

|

|

VIDEO

|

|

CNN's Charles Bierbauer reports on High Court's decision.

CNN's Charles Bierbauer reports on High Court's decision.

|

|

Real

|

28K

|

80K

|

|

Windows Media

|

28K

|

80K

|

|

Still, the decision means it could be years before the case reaches a conclusion, something that Microsoft clearly favors as it battles the government's claim that Microsoft used its dominance in the operating system market to squash competitors.

For an overview of the Microsoft case, click here.

Shares of Microsoft reacted favorably to the news, rising $1.44, or 2.3 percent, to $62.69 on a day when many other technology stocks traded lower.

In an appearance on CNNfn, Microsoft President and Chief Executive Steve Ballmer said Microsoft would have been happy to argue its case before the Supreme Court or the Appeals Court and that Tuesday's decision was "just a small procedural step." [209K WAV, 209K AIF]

Appeals Court acts rapidly

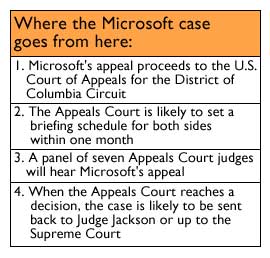

The Appeals Court reacted rapidly to Tuesday's Supreme Court decision, ordering the two sides to propose schedules and a format for the appeals process by Oct. 2. Responses to the proposed briefing schedule are to be filed by Oct. 5 and any further replies by Oct. 10, the D.C. Appeals Court said.

"The parties may, if practicable, submit a joint proposal," the court added.

The Justice Department said that it is "looking forward to presenting our case to the Court of Appeals as soon as possible."

Iowa Attorney General Tom Miller, one of the lead attorneys general in the state case against Microsoft, said that the states are disappointed that the Supreme Court declined to hear arguments in the Microsoft case. "We continue to believe that prompt and final resolution of this case is in the public interest, and that the Supreme Court is the most appropriate forum for that resolution," Miller said in a statement. Iowa Attorney General Tom Miller, one of the lead attorneys general in the state case against Microsoft, said that the states are disappointed that the Supreme Court declined to hear arguments in the Microsoft case. "We continue to believe that prompt and final resolution of this case is in the public interest, and that the Supreme Court is the most appropriate forum for that resolution," Miller said in a statement.

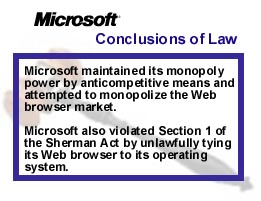

On April 3, Judge Jackson concluded that Microsoft had violated federal antitrust law by maintaining its near monopoly over personal computer operating systems by anticompetitive means and by attempting to monopolize the Web browser market. He also found that the software maker violated federal antitrust law by tying its Web browser to its operating system when it released Windows 98.

Last June, Jackson issued a final order that requires Microsoft to separate its Windows operating system business from its applications business and bars the company from engaging in practices that the court found led to the antitrust law violations. However, Jackson's order doesn't go into effect until Microsoft has exhausted its appeals.

Of the nine Supreme Court justices, only one -- Justice Stephen G. Breyer - dissented.

"Speed in reaching a final decision may help create legal certainty," Breyer wrote, contending that the Supreme Court should hear the case now.

Chief Justice William Rehnquist also issued a statement noting his son works for one of the law firms representing Microsoft. Rehnquist said after consideration he decided he would not recuse himself from the case.

Future schedule for appeal

Mark Popofsky -- a lawyer who worked in the Justice Department's antitrust division between 1994 and 1999 and who now is a partner at Kaye, Scholer, Fierman, Hays & Handler -- said the Supreme Court's decision will add another year to the final resolution of the case. He expects the Appeals Court to reach a decision in the Spring of 2001, at which point the case may go back to Jackson or up to the Supreme Court. In either case, the final resolution is not likely to come until the Spring of 2002, he said.

"The odds of settlement are low," Popofsky said. "Microsoft probably sees some advantage in delay."

Donald Falk, a lawyer at Mayer, Brown & Platt specializing in antitrust law and appellate litigation, said that sending the case back to the Appeals Court means that it will not reach final resolution until two to three years from now, rather than one year if the Supreme Court had agreed to hear the case directly.

"None of the judges in the D.C. Circuit has seen the record in this case yet, which leaves everything open to complete reconsideration," Falk told CNNfn.com.

George S. Cary, an antitrust lawyer in the Washington office of Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton, said the delays associated with having the Appeals Court review the case make the antitrust proceedings more vulnerable to political interference, especially if George W. Bush wins the presidential election.

"The longer the thing stretches out, the more opportunity there is for a new attorney general to cut a deal," he said.

Appeals Court cases normally are heard by a panel of three judges. However, in an unusual move, the D.C. Appeals Court said last June that it would hear the appeal "en banc," which means by a full panel of 7 judges.

Three Appeals Court judges had recused themselves from the case because of potential conflicts of interest, and there are two vacant judge positions.

Star players will be absent

The star attorneys who represented the Justice Department and the

19 states in the first round of the antitrust case, which began in May 1998, will not be present for the appeal. The Justice Department's head of antitrust enforcement, Joel Klein, plans to resign at the end of this month.

Attorney General Janet Reno selected Klein's deputy, Doug Melamed, to be the acting assistant attorney general for antitrust enforcement. Melamed is regarded as a highly competent attorney who shares Klein's views on antitrust enforcement.

At the same time, the government's star outside counsel, David Boies, has decided that he will not handle the appeals phase of the Microsoft case. A former partner at the New York law firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore, Boies launched his own firm in 1997, which has since grown to more than 60 lawyers. The Armonk, N.Y.-based firm Boies, Schiller & Flexner, now has turned its attention to defending the music Web site Napster, handling a class-action lawsuit against HMOs, suing Sotheby's and Christie's auction houses for antitrust law violations, and representing Calvin Klein in a dispute with Warnaco.

Microsoft's plan of attack

Microsoft has indicated in previous court filings that it plans to attack both Judge Jackson's findings and the validity of the remedy he imposed on the software giant, which Microsoft views as draconian and totally out of proportion to the alleged antitrust offenses.

For example, Microsoft said in June that Jackson had made so many mistakes in his ruling that an appeals court needed to sort them out before the case could be passed to a higher court.

"Microsoft intends to challenge many of the court's findings as clearly erroneous," Microsoft said in the June brief, adding that "addressing those subjects alone would require review of the 13,466-page trial transcript and the 2,695 trial exhibits that comprise the record in these cases, a time-consuming exercise the Supreme Court would not likely be anxious to undertake."

"It's not without basis to say that the Court of Appeals is the preferred place for Microsoft," said Robert Litan, vice president and director of the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C. "But normally on fact finding, appeals judges give great deference to a lower court."

The weakest part of the government's case is the claim that Microsoft violated antitrust laws by incorporating its Explorer Web browser into its Windows operating system, antitrust lawyers said. In 1998, the D.C. Appeals Court found that Microsoft would not be in violation of a consent decree it had reached with the government if it combined Windows and Internet Explorer. Antitrust lawyers note that in the 1998 case, the Appeals Court was interpreting a consent decree, which is essentially a private contract between two parties, rather than federal antitrust law.

When Jackson issued his legal conclusions in the Microsoft case last April, he disregarded the Appeals Court's findings in the consent decree dispute, saying that the issue before the Appeals Court was "the construction to be placed upon a single provision of a consent decree that, although animated by antitrust considerations, was nevertheless still primarily a matter of determining contractual intent."

Even if Microsoft manages to overturn that portion of Judge Jackson's conclusions of law, the company still is far from being out of the woods.

"Even if they slap Jackson down on the tying issue, there still will be the rest of the verdict," Litan said.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|