|

Scams against the elderly

|

|

October 13, 2000: 5:57 p.m. ET

Here's how to tell if somebody is bilking money from someone you love

By Staff Writer Martine Costello

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - Audrey Smith never suspected anything was wrong when she would call her 80-year-old aunt and the caregivers said she couldn't come to the phone. Some days, her aunt was "tired." Other days, her aunt was "sleeping."

Smith figured her aunt was mad at her, or didn't want to keep in touch any more. She felt hurt, so she eventually stopped calling.

It wasn't until Smith got a call from some state officials that she learned the truth. Her aunt -- the granddaughter of a former Kansas governor and a gifted musician who performed with a symphony -- had been the victim of a terrible scam.

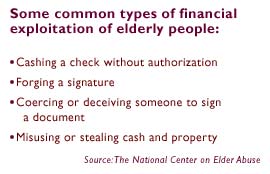

The caregivers had befriended the woman, coerced her to change her will, then sold her possessions and cleaned out her bank account of several hundred thousand dollars. The caregivers had befriended the woman, coerced her to change her will, then sold her possessions and cleaned out her bank account of several hundred thousand dollars.

"I feel so guilty about not pushing the issue," said Smith, who lives in Texas. "I would call and she just never came to the phone. She was just unavailable."

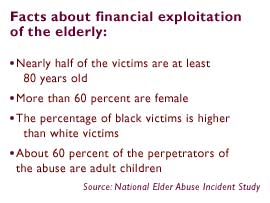

Often frail and alone, elderly people are easy targets for con artists or self-serving relatives who weasel into their lives and steal them blind. And by the time anybody figures out what's going on, the money is gone, the elderly person is devastated and penniless in a nursing home.

From Florida to California, health-care providers, prosecutors, investors and heartbroken family members tell stories that are eerily familiar. Often, it's an adult child or grandchild who feels "entitled" to the assets. Mom would have wanted me to have it. Other times, it's a caregiver or a neighbor. Let me be your power of attorney and I'll handle all of your bills.

Most times, nobody gets punished because the victims are embarrassed and don't want to testify. Or they are so frail they wouldn't make good witnesses. The cases are a nightmare of paperwork to unravel.

"The problem is much more extensive than we know about," said Robert Flemming, an attorney who handles such cases in Tucson, Ariz. "A lot of times the person is embarrassed and doesn't want anyone to know."

All in the family

While cons against the aged are on the rise, the classic case is when an adult child lives with an aging parent, Flemming said. The child may have made some sacrifices to care for the parent, and over time feels entitled to dip into the money.

"They'll say to themselves, 'Mom is riding in my car quite a lot,' so she won't mind paying for my tires," Flemming said. "Pretty soon, assets are being used to support the child's life."

The aging parent may give the child power of attorney to sign bills and manage affairs.

"A power of attorney is literally a license to steal," Flemming said. "It's a very dangerous instrument. You absolutely have to trust the person you give power of attorney to." "A power of attorney is literally a license to steal," Flemming said. "It's a very dangerous instrument. You absolutely have to trust the person you give power of attorney to."

Robert Jackson, an attorney who specializes in elder law cases in Florida, said a child may trick a parent into signing over a house to him to "avoid estate taxes." But the house will be exempt from estate taxes because it is worth less than the $675,000 exemption. Or, they may dip into a parent's account to pay for a vacation.

"People take liberties and one thing leads to another," Jackson said.

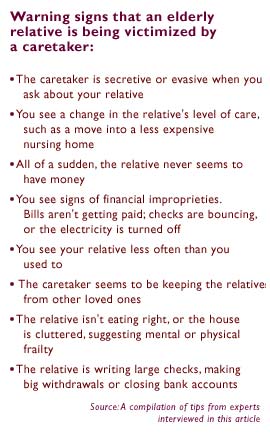

One warning sign is that the caretaker child will try to keep the relative from other family members.

"What I see is people take their childhood issues into adulthood," said Susan Haines, an elder law attorney in Glendale, Colo. "When Mom and Dad are no longer competent the feeding frenzy starts."

Family members who suspect a relative is misusing a power of attorney can go to court -- the rules are different in every state -- to lodge a challenge. The court will require the power of attorney to show how he or she has been using the money. The person with the power of attorney, the elderly person, and the person challenging the issue will all need their own lawyers. The judge may appoint a guardian to oversee the money.

"It's very tragic, because if you have an elderly person who is wiped out, it's pretty hard to recoup their life savings," said Becky Morgan, a professor specializing in elder law at Stetson University College of Law in Florida. "A lot of times, elderly folks don't want to get their children in trouble. Or they fear they might end up in a nursing home."

Loneliness and new friends

One state investigator from the Midwest who didn't want to be named said you should always be on alert if your elderly loved one has a "new best friend."

Often, elderly people live far away from their family, making it easy for a con artist to sweet-talk them.

In one case, a woman in her mid 70s was estranged from her two sons. Her caregiver befriended her, started calling her "Mom," and moved in. Eventually, the caregiver ran up huge credit card bills, then moved out when the money ran dry. In one case, a woman in her mid 70s was estranged from her two sons. Her caregiver befriended her, started calling her "Mom," and moved in. Eventually, the caregiver ran up huge credit card bills, then moved out when the money ran dry.

"The mom was mad the sons wouldn't pay attention to her," the investigator said. "She was showing her sons that somebody loved her more than they did. These cases are extremely complicated to figure out. There's an awful lot of paperwork you have to wade through."

Nick Cox, assistant attorney general in the Florida Attorney General's office, said sometimes seniors don't believe they are victims. In one case, a woman in her 80s grew attached to a 50-year-old male instructor at a dance studio. The man took her to dance contests in Miami and Atlanta, and she gave the dance studio about $300,000 over the course of a year.

"The man made her feel great, but once she ran out of money, that was it," Cox said. "He went on to somebody else. But even then, she didn't think anything was wrong."

Turning the heat up in court

It used to be hard to prosecute such cases, but the trend is changing.

"If somebody suspects something is going on, he should call the police, call the Attorney General's office, call Consumer Protection," Cox said. "The most important thing is to be involved with your elderly relative. Spend time with them."

But be prepared for hard work. Pearl Olson, 50, of Mount Rainier, Washington, spent nearly two years building a case against a woman who convinced Olson's father to give her half of his life savings. But be prepared for hard work. Pearl Olson, 50, of Mount Rainier, Washington, spent nearly two years building a case against a woman who convinced Olson's father to give her half of his life savings.

Olson's father, William Jack Olson, now 80, was a retired engineer living in an elderly complex in Beaverton, Ore. A woman working in the cafeteria befriended him and told him she was broke trying to get treatment for her son for sickle cell anemia. Over time he gave her more than $40,000, according to Pearl Olson and police.

"He was giving her $1,000 a week in cash," Pearl Olson said. "This was not disposable income. My dad was draining his bank account...He absolutely and totally believed her."

Pearl Olson and her sister tried for months to convince their father that he was being deceived. They hired a private detective, pored over bank records, and pushed police to pursue the case.

The cafeteria worker, Patricia Ann Mitchell, 38, was later convicted of one count of aggravated theft in the first degree and ordered to repay $41,242 in restitution in monthly installments of $400 as part of a plea agreement, court records show.

The case took its toll on William Olson. He was hospitalized for heart problems and psychiatric problems. He's still not recovered completely.

Now, Pearl Olson believes other people may have been victimized by Mitchell. She's asking people to e-mail her at victimnomore@earthlink.net. She also wants to help others in the same situation.

"He completely fell apart," Pearl Olson said. "We want to help other victims. We know how to find the bank records. We know what hoops to go through, and it wasn't easy."

Chris Colburn, Mitchell's public defender, said he understands the family's outrage.

"Patricia feels awful about it," Colburn said. "That doesn't mean she's done it to a million people ... I'm concerned the family is taking over the investigation."

For Audrey Smith, the woman from Texas whose aunt in Kansas was victimized, the story did not end with a conviction or restitution.

Click here to read more senior living stories on CNNfn.com.

Neighbors started noticing moving trucks at her aunt's home. Her aunt was a frail woman with diabetes and dementia, and the caregivers left her neglected in her bed. The state put her in a nursing home and she died about a year later.

The caregivers disappeared. Smith tried to get an earlier will reinstated, which left a little money to Smith's children and provided for her aunt's beloved 13 cats and five dogs. Smith had also hoped to set up a scholarship in her aunt's name. But a deadline had passed, so the last will is in effect. The money is sitting in an account, and two of her aunt's instruments are locked in an administrator's office.

"I would advise people to step forward and do something," Smith said. "I've lost a lot of sleep over this."

-- Click here to send e-mail to Martine Costello

|

|

|

|

|

|

|