|

Getting started: Horse farms

|

|

April 30, 2001: 10:51 a.m. ET

Go to work in a picturebook setting; expensive to start

By Hope Hamashige

|

NEW YORK (CNNfn) - It's impossible to whittle down the appeal of raising thoroughbred horses to one single factor. It is tinted with charm, romance and tradition. It presents constant intellectual challenges as well as agricultural ones. And then there's the thrill of seeing a horse born and raised on your farm cross the finish line a nose ahead of a field of its peers.

"It's thrilling," said John Phillips, a third generation Kentucky horse farmer who owns Darby Dan Farm in Lexington. "There's birth and death and frustration and victory in raising horses. It's like a little microcosm of life is built into the short lives of these creatures."

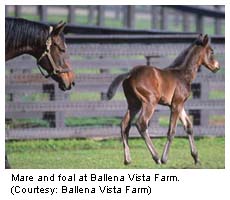

The allure of a horse farm is a compelling one, particularly at this time of  year. It's spring. The dogwoods and redbuds are in full bloom all around horse country. The farms are flush with foals stretching their new legs in the pastures and growing strong munching on Kentucky bluegrass. And on Saturday, several farmers will watch breathlessly as a horse born on their farm runs the Kentucky Derby. year. It's spring. The dogwoods and redbuds are in full bloom all around horse country. The farms are flush with foals stretching their new legs in the pastures and growing strong munching on Kentucky bluegrass. And on Saturday, several farmers will watch breathlessly as a horse born on their farm runs the Kentucky Derby.

No doubt, say those who are in the business of raising horses, that this is great way to make a living if you are passionate about these elegant creatures. No doubt, too, that there are much easier ways to make a living.

Horse farming is both capital and labor intensive. Both the animals and the farm require constant attention. It's an extraordinarily risky business. But, as in many high-risk businesses, there also lies the possibility of high reward.

Setting up can cost millions

"I don't like to think about how much I've spent in the past 10 years," said Don Cohn, the owner of Ballena Vista Farm in Ramona, Calif. "We have spent millions -- millions."

That someone getting into horse farming would spend millions of dollars surprises few in this industry. Consider all the expenses that go into this type of enterprise: There's land to buy, pastures to fence, barns to build, farm equipment to purchase, and farm hands to employ. And if you're not an expert at raising equines, you had best find someone, an experienced farm manager, to guide you.

"Any kind of agriculture is hard to get into and this is no exception," said Phillips. "The margins tend to be low, although they can get higher when you are farming thoroughbreds."

The high cost of entry is the reason most thoroughbred farms start small. Robert Clay, who owns Three Chimney Farm in Lexington, opened in 1973 with 100 acres. He kept his day job at a fertilizer company for about 10 years until he could leap into raising thoroughbreds full time. His farm has grown since the mid-1980s to 1,500 acres with 300 mares, 100 yearlings, 200 foals and 11 stallions, including the last living Triple Crown winner, Seattle Slew.

Cohn opened his farm 10 years ago and has been slowly adding acreage and amenities since. For Cohn, who worked as a vet assistant on a horse farm as a teen, the business is a realization of a boyhood dream. After years in real estate development and high technology, however, he found he needed to spend most of his time in the early years establishing ties with the horse community and making a name for Ballena Vista.

"I thought it was going to be like "Field of Dreams" and if I built it they would come," he said. "It's not that easy."

Others start out in horse racing as owners and later decide to build a farm, and they build the farm up on the reputation of the horses they raced as owners.

A lot of expertise and a little luck

Once a farm is up and running it doesn't get any easier.

"Owning a horse farm is a little like being the headmaster at a prestigious boarding school," Clay said. "Its like having people's children come to live with you and you are responsible for looking after them."

Boarding horses is both capital intensive and labor intensive. Like any agricultural enterprise, a horse farm needs constant upkeep. Barns and fences almost always need some kind of repair. Horses need exercise, fresh oats and clean hay. Soil must be tested to make sure the horses are getting proper nutrients. And the pastures are always kept picture-perfect. Veterinarians, too, make regular visits to check on the health of the animals.

Add some administrative help and you have a full-time functioning farm. And when you factor in supplies and labor, you may have operational costs that run well into the millions.

Clay and Jim Frees, the farm manager at Claiborne Farm in Lexington, agreed that most farms try, at best, to break even on boarding. The real money on the big farms comes from breeding and selling horses.

That, too, as with most everything in horse racing, can be extremely expensive and a real gamble. Successful breeding at most horse farms hinges on getting a big name stud on board, and that is either going to cost money or come about by raising excellent horses, but also getting just a little lucky.

Take last year's Kentucky Derby winner, for example. Fusaichi Pegasus was sold last June by his Japanese owner to an Irish farm called Coolmore Stud for a reported $70 million. He will command huge stud fees, estimated to be around $200,000 per live birth his first year, as do many big-name horses. But getting a top stallion in a stable, a prize winner that commands top-dollar stud fees, comes with a high price tag.

Some farms get a little luckier. John Harris, a big name in California cattle ranching, is also making a name for himself in the world of horse racing because a stallion he owns produced a colt named Tiznow. Tiznow became the first Californian to be named "Horse of the Year" in about four decades after winning $3.4 million in nine starts. Harris now expects other offspring of Cee's Tizzy to fetch more at sale. And Harris can charge much higher stud fees.

"You never know how close you are to having a top horse," Harris said. "It's not an exact science and it can really happen overnight."

Horse farm owners also commonly take boarders to sales for a commission of around 5 percent. This, Clay said, is the way boarding works into profits. The better shape you keep the horses in, the better boarders you have, and when they are sold at auction the farmer gets a much bigger commission. Clay, for example, said he took $33 million worth of horses to sale last year. At a 5 percent commission, that's a decent $1.65 million for Clay.

There are some regional differences, too, in the way horse farms make money. In California, where the bloodlines of the thoroughbreds run thinner than in Kentucky, most horse farm owners also race their own horses in the hope of bringing in some extra cash.

As with any agricultural endeavor, however, there are so many unpredictable factors that can affect profits. A particularly bitter winter will mean higher hay and heating costs for New York farmers. There also are occasions when mares simply don't get pregnant. And, on farms, there always seems to be tragedy. Horses die during foaling and the foals don't always make it to adulthood.

The search for the next Secretariat

For others, though, the rewards are less monetary. Some, like Pat Youngman who owns Pepper Oaks in Santa Ynez, Calif., don't mind dragging themselves out of bed in the middle of the night because a mare is giving birth. What she loves about this business is not the money, but knowing she is helping to raise beautiful, healthy horses.

There are those who love the search, who love scanning their pastures filled with yearlings and foals, looking for the swift and competitive among them that could take all or one of the Triple Crown events.

"Every decade there is an instance where someone finds the unbelievable horse," Phillips said. "And the road to that dream is, in itself, exciting."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|