|

Little giant ladders stretch out

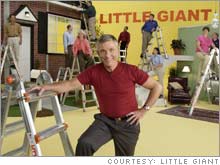

From humble beginnings, the Little Giant Ladder grows to a big business for the Wing family.

NEW YORK (CNN/Money) - In the 1950s, the U.S. Army sent Hal Wing to Germany. He met and married his wife and brought her home to Utah where they raised a family and he worked in insurance. He had, however, become infatuated with all things Teutonic. So when his company opened a German branch in the 1970s, Wing jumped at the chance to go back.

One day after the family's return, "A friend dragged my dad over to see this crazy ladder a painter had invented," says son Art. Hal asked the painter, Walter Kümmerlin, if he had tried to sell the articulated, multi-purpose tool in the United States. He had, without success. "Europeans are much more interested than Americans in compact, multi-use tools," says Art. "They have smaller homes and cars, and less storage room." Wing took a sample home and showed it to friends, contractors, and other businessmen. Their positive response led him to quit his job, take his life's savings, and order a 20-foot container of the ladders. It was the beginning of Wing Enterprises, purveyor of the Little Giant Ladder, the "Swiss Army Knife" of ladders. First steps to success

Hal Wing took the ladders around to the same people whose initial response had so encouraged him, except now, nobody wanted one. The resistance stemmed from several sources:

The only venue where Wing could sell the things were trade shows and fairs. There, he tapped his natural showmanship and demonstrated the ladder's 24 different configurations. For the next three or four years, Hal spent up to 300 days a year on the road. Sales got harder when, in the late 1970s, the German mark rose to near par with the dollar, increasing the price of the already expensive tool. Hal's response was to work out a licensing agreement with the Germans, and start producing the first American-made Little Giant. The company was soon grossing $1 million to $1.5 million a year. Hal improved the design, putting in a special, strong hinge, patenting a trapezoidal step that laid flat, and increasing leg flare for safety. Sales gained traction. Payless Shoes bought thousands, figuring the safety factor would save them in workmen's comp and insurance costs. AT&T liked them because they could be transported inside a van, saving the cost of a roof rack. And by the early 1980s, the Little Giant had become standard Air Force equipment. The ladder could be set up with one side at 90 degrees, enabling maintenance crews to work close to F16 fighters, where they could place it near the fighter without touching the plane's tender skin. Reversal of fortune

Raising seven kids, Hal was a little strapped for cash and he sold a stake in the company to two partners in 1981. "They said they would bring in $335,000, but they only invested $87,000 at 10 percent interest," he says. Five years later, after they sold control to a conglomerate called Technical Equities, which was buying up small companies and raiding their lines of credit, the company went under. Hal walked away with little to show for years of hard work. In March 1986, Little Giant's assets went on the block at a Sheriff's sale. Hal bought it back, getting financing from a bank on the strength of his word. Then he went to every supplier that Little Giant owed and told them if they'd work with him, he would pay everything back, a total of $1.8 million. "He didn't have to do that," says Art, "He only bought the company's assets, not liabilities." But wait, there's more

Hal paid off the debts and grew sales at double-digit rates. By 2003, he had a nice, steady $20 million a year company. The question was how to get to the next level. The answer: infomercials. The company hired Dean Johnson and Robin Hartl of the syndicated home-improvement show "Hometime," to host. "We avoided the 'How much would you pay? But wait, there's more' infomercial style," says Art, in favor of straight demonstrations. Orders took off as never before, straining supply lines. "It went terribly wrong, but in a good way," Art remembers. The company maxed out production by going 24/7 and barely managed to keep up. Revenue sextupled in 2004 and has risen another 40 percent in 2005, enough to win Hal an Entrepreneur of the year from Ernst & Young. The company now grosses in nine figures. Ex-"Tool Time" ("Home Improvement") co-host Al Borland (the actor Richard Karn) helps host the current iteration of the infomercial. Art says channel surfers will pause to watch Karn because of the actor's "Home Improvement" persona. The Little Giant should get a little bigger over the next few years. The name recognition has improved, enabling the company to run shorter spots and sell the product through mass marketers such as Sears and True Value. Wing Enterprises is already the largest manufacturer of American-made ladders. It was a long climb. ---------------------------- The business Anne Mahle and Jon Finger started is on cruise control. Click here for their story.

There are lots of opportunity for growth in these franchises with futures. Click here for more. |

|