The grand scheme of the Swedish Match King

Exclusive book excerpt: How industrialist Ivar Kreuger went from worldwide prestige in the 1920s to infamy just a few years later.

|

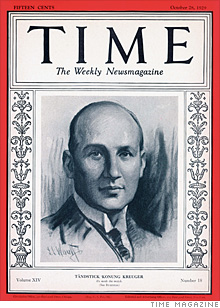

| Ivar Kreuger, the 'Swedish Match King' on the Oct. 28, 1929 issue of Time |

(Fortune) -- In the 1920s, Ivar Kreuger was known as the savior of Europe. A month after his death in 1932, he was known as its greatest swindler. What follows is an excerpt from a chapter in Fortune's new book, "Scandal!," drawn from a three-part Fortune series on the man who would be the world's match king - but whose hubris left his reputation in ashes.

Land reform in Estonia; the migration of Greeks and Turks; the building of railways in Peru; Mussolini in full spout: All these events are linked by the suicide of a man in a Paris apartment in March 1932. And that man, Ivar Kreuger, was the heart and brain of one of the greatest business scandals of all time.

At the peak of his fame in the late 1920s, he was easily the most respected business man in the world, and the shares in his company, Swedish Match, were the most widely traded. He invented the "B" share. He was referred to as the "savior of Europe" for providing loans to cash-strapped countries in the aftermath of the Great War.

The Kreuger empire was built on the humblest of things - the match. And in fact, Swedish Match really did make matches, but it was also a complicated pyramid scheme that fleeced tens of thousands of American investors.

In a series that ran in May, June, and July 1933 - the same year he won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry - Fortune writer Archibald MacLeish laid out the entire history of Ivar Kreuger. An excerpt:

On April 15, 1932, it was announced to an already hysterical world that the great financier, the creditor of governments, was not only suicidal and not only bankrupt but a very clumsy forger of bad bonds. Hell, in the expressive phrase, broke with that news. The whole structure of the Swedish state was shaken.

Prime Minister Ekman was forced to resign. The foreign exchange reserves of the Swedish central bank were weakened and the powerful financiers, the Wallenbergs, were forced to intervene. Municipal tax collections fell by 10% and membership in the Communist Party doubled. Many of the richest men of the country were bankrupt. The king's brother Carl, father of the Crown Princesses of Norway and Belgium, moved into humble quarters. The racing season collapsed. Kreuger's furniture and pictures and towels were sold at auctions in Stockholm, London, Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin.

But these events were merely consequences, repercussions. They explained nothing. The real question was still in the summer of 1932, as it had been on the March 12, the day he died: What was it precisely that had happened? Was Ivar Kreuger really a common crook? If he was a crook, how long had he been a crook?

As rumor fed rumor, only the employees of Price, Waterhouse and Company were in a position to apply the hard edge of fact.

All through the summer and fall of 1932, 30 men and a dozen calculating machines and hundreds of ledgers and great stacks of correspondence were collaborating in the writing of 57 fact-finding reports. What the accountants discovered was that Kreuger's career in the years from 1911 to 1923 had been approximately what the world believed it to be.

The central story, the official account, was clear enough. Born in 1880 of a bourgeois family in the little Swedish wooden town of Kalmar, Kreuger had worked through grammar school and technical college, emigrated to America at the age of 20, tried real estate and wire stringing, worked on a bridge in Vera Cruz and on the Flatiron Building, Macy's, the Metropolitan Life Building and the Plaza in New York, tried his luck with a construction company in London in 1903, started a Johannesburg restaurant, served a hitch in the British Militia at the Cape, passed three months in Paris at the age of 24, swung back to Canada and the States, worked on the Syracuse Stadium, and ended up in Sweden in 1907 with no money, a sound knowledge of reinforced concrete, and an ambition to rebuild the city of Stockholm.

At 30, Kreuger had joined forces with a young Swedish engineer named Toll, run away with the building business in Stockholm, extended his interests into Finland, Russia, and Germany, turned to the family match business in 1913, formed Swedish Match in 1917 in the face of enormous and worldwide difficulties, and by shrewd management and consolidation restored to Sweden her predominance in match production.

Kreuger the builder and Kreuger the Match King were not frauds. Both existed. Both made large and apparently justifiable profits. From 1917 to 1924, the Swedish Match Company paid dividends of 12% or better and Kreuger and Toll paid dividends of 20% or more. In 1923, Kreuger was a great industrialist and his companies were approximately what they represented themselves to be.

From about 1923 until his suicide in Paris, the colors changed. What the world knew, or thought it knew, was that Kreuger extended the Match Trust's operations into every European country except Spain, Russia, and France and to 16 non-European countries, bought or built 250 match factories, set up fabulous subsidiaries in America, acquired absolute monopolies in 15 countries, associated with himself the great banking names of Europe and America and lent almost $400 million to 15 countries including France and Germany at a time when Europe was desperately short of credits.

His interests touched the world at every point. His telephone company, Ericsson, had factories in 12 countries and concessions in five. His Swedish Pulp Company was the largest European producer of sulphite and sulphate pulp. The Swedish Film Industry Company was one of his companies.

Though some of the assets were real, the entire foundation was a financial fantasy. Until 1923, Kreuger was a moderately honest man and an industrialist by profession; after, he became an immoderately dishonest man and a stock promoter by trade. In that year, Kreuger, with his passion for power, discovered the New York glut of gold and the inexhaustible New York appetite for stocks.

In doing so, he discovered the superiority of the stock market to the match factory as a means of conquest. There is only one conclusion: In 1923 and 1924 Kreuger and Toll changed from a productive entity to a Stock Exchange show window.

What Kreuger was playing was nothing more subtle or more intelligent than the old Ponzi game. He was paying dividends out of capital. And trusting to more capital to make good the loss. And there was no possible outcome but disaster. The only question was: How long disaster could be deferred?

October 1929 is the date of catastrophe. From that time on, and with an increasingly rapid fatality, events which Ivar Kreuger could no longer control beat in upon him and eventually beat him down. What Kreuger himself thought of his situation may be guessed from the fact that it was in the fall of 1929 that he undertook to lend the German government (which was in ill odor thanks to the rise of Adolf Hitler) the enormous sum of $125 million.

Nothing in Kreuger's career has more amazed his many biographers than this suicidal loan made in the shadow of the great Depression to a nation with impaired credit by a man whose securities would not sell. But in fact nothing is more logical. Only by an act of desperate courage capable of restoring his slipping prestige could Kreuger ever extricate himself. And the German loan was precisely the act required.

Had the times changed, that act of insolent daring might have succeeded. As it was it came within a stone's throw of success. The French, instigated by some divinity, redeemed their loan in April, freeing $75 million of much-needed cash. But as the 29th of May 1931 drew on, it became more and more apparent that there was to be no further intervention of a god.

Unless Kreuger himself should do the intervening. And Kreuger had nothing with which to intervene. Short of a miracle, the jig was up.

It was Kreuger who performed the miracle. And out of the emptiest hat. Or rather out of the Italian coat-of-arms on the flap of an old envelope, a little ink, and 46 embossed and printed sheets. The envelope came from Kreuger's drawer. The printed sheets were provided by an honest Stockholm printer. And the ink Kreuger himself applied sitting late in the great office at the Match Palace laboriously and clumsily forging the signatures to £28,668,500 of worthless Italian bonds. Pencil tracing showed under some. And the brief Italian phrases were, on certain of the bonds, not even good Italian. Nine million pounds of these bonds were wedged into the statement of Kreuger and Toll for 1930.

The crisis was passed. But another crisis immediately replaced it - the July dividends. To meet them Kreuger determined upon what was to him the most desperate act of his career - the sale of the controlling interest in Ericsson. But Kreuger had no choice. He went to America in the summer of 1931, arranged for an exchange of stock between I.T. and T. and Ericsson and the payment by the former of $11 million. From New York he returned to Stockholm.

But there was no truce with fate. Danger now threatened in New York. I.T. and T. was threatening to check the Ericsson books. On December 22, 1931, Kreuger reappeared in New York. Largely out of his own head, he dictated the annual report of Kreuger and Toll for 1931, painting a picture which was calculated to sweep another score of New York millions into his empty tills. But New York in January 1932 was in no mood whatever to respond.

And while he waited, while he listened, while he talked, the blow had fallen. The game was played. I. =T. and T.'s auditors in Stockholm had discovered that an asset item of 27 million kronor cash on the books of Ericsson was really only a claim against Kreuger companies in that amount. There was no adequate explanation. The catastrophe was complete.

Kreuger had not only squeezed the last sponge of credit dry. He had also played the market. He had been playing it for two years, using the funds of Kreuger and Toll and the services, under one name or another, of most of the brokerage houses of New York. Millions of dollars were gone, in support of a fatally falling market.

There on the 21st of February was Kreuger in New York, his credit gone, his Ericsson contract rescinded, his reputation impugned, losing millions on a falling Stock Exchange, issuing falsely comforting statements, borrowing a last feeble $1.2 million from Swedish banks to pay interest on debentures and trying to make sense while the men from Lee, Higginson, his Boston-based U.S. bankers, called to advise him to take a rest.

The telephone was going day and night. The housekeeper, Hilda Aberg, was buying an alarm clock to waken him for transatlantic calls past midnight. People were coming in to see him at all hours. He began smoking - lighting cigarettes rather - and playing solitaire sitting at his desk. He was more and more nervous. One day he came in with a package 40 inches long. He stood it in a corner in his bedroom.

The night before he left he was telephoning and telegraphing and sending messengers with wrong addresses and saying, What is it? What is it? At 8 in the morning Hilda went in to waken him. He was lying on the bed fully dressed, only his coat off and his shoes beside him on the blankets. He refused to change his clothes.

When he came out to breakfast there was shaving cream smeared on his tie. Hilda went in to make his bed when he was gone. There was a slip of paper on the table by the bed. It said: "I am too tired to continue." Telegrams came in. The telephone was ringing all day long, but he was not there. He was not there or at his office. The next day when he was gone Hilda opened the tall package 40 inches long. It was a loaded rifle.

So, how much vanished? The answer starts at $250 million and goes up to $400 million (about $10 billion in current dollars). These are guesses; what can be said with certainty is that when Kreuger's U.S. operations were declared bankrupt in August 1932, it was the largest to that date.

As a result of this particular debacle, Congress eventually passed the Trust Indenture Act in 1939, which regulates the use of collateral in borrowings. In general, there is no doubt that the Kreuger story played a large role in the creation of the SEC.

Winding up the Kreuger enterprises took years; the bankruptcy trustees in the U.S. issued their final report in 1945, and eventually U.S. investors got back about 30 cents on the dollar. The genuine Kreuger assets were able to resume business; some descendants operate still. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More