Search News

PwC chairman Bob Moritz with the winners of PowerPitch

FORTUNE -- In the hallway outside the auditorium, six twenty-something women stand in a knot, twisting their hands, taking deep breaths, and offering each other mini pep talks to calm their nerves. The stage is prepped and waiting: Spotlights illuminate the six black leather stools where the group will perch, less than an hour from now, as they are grilled by a panel of judges, their performances avidly watched around the country.

After 20 minutes, the deep breaths aren't working, and one of the women says, "Let's go have a dance party." Minutes later, they're in the women's restroom laughing and grooving out their anxieties to Madonna's "Like a Prayer," which plays through a BlackBerry. Down the hall, a competing team of four men and two women opts for motivational speeches from the movies Any Given Sunday and Miracle, delivered on a laptop via YouTube. Three other finalist groups pace nearby, some flipping through crib notes, others silently mouthing the words to presentations they've rehearsed 100 times.

|

| Mitra Best, who hatched the idea for PowerPitch |

There's $100,000 on the line, and nine months of preparation has come down to four tense minutes on stage plus five minutes of cross-examination by the judges. It's not American Idol, though this competition has been modeled on the talent search juggernaut. Instead, it's a late-July morning in the Manhattan headquarters of PricewaterhouseCoopers, the accounting and consulting titan whose elite client list includes the vast majority of the Fortune 500. And the audience is about to see the climax of an even more lucrative quest: the search for PwC's next $100 million business -- not to mention its next generation of stars.

Idea generation from a new generation

PowerPitch, a firm-wide innovation contest launched by PwC last November, is the brainchild of Mitra Best, a former engineer who now has a broader role and the title "innovation leader." Best and her colleagues are determined to harness the creativity of all PwC employees. In an era of scrawny margins, ferocious competition, and a shaky global economy, missing out on profitable ideas feels not just foolish but irresponsible. "We started realizing we had to look beyond just the R&D centers as a source of innovation," she says.

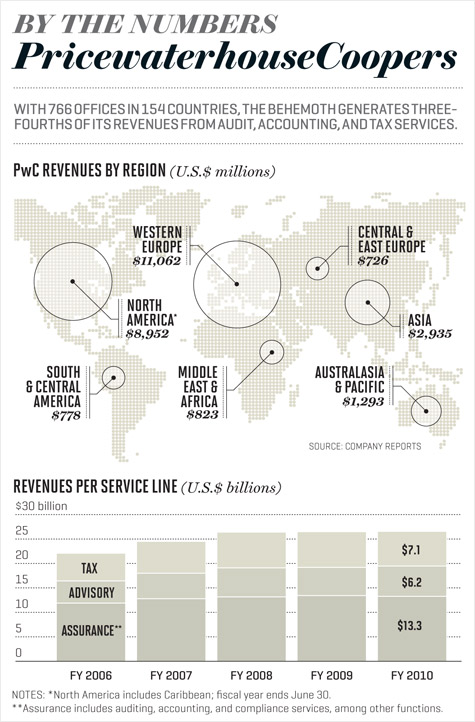

And PwC wants to cultivate a particular atmosphere. "We have an average age of 27, but we have roots in tax and assurance," says U.S. chairman Bob Moritz, using the industry jargon for auditing and related functions. "So how do you make this place feel like a Google (GOOG, Fortune 500) or a Facebook? A place that feels leading-edge?"

An admitted fan of American Idol and The Apprentice, Best was drawn to the idea that contests and games could yield serious business results. Employees love the opportunity. "It's selfish, really," says Zachary Capozzi, 25, a senior financial services associate in PwC's Chicago office, who led one of the finalist teams. "We're interested in doing what we'd proposed. In fact, we'd suggested it in the past but were directed elsewhere. Knowing that right now, if there's an idea, people actually want to hear it? It makes you feel in control."

Best also wanted the competition to borrow from the videogame world, with live chats and an online platform for discussion and voting. "We tried to create a collaborative and competitive environment. This was not like inspiring 50 people, or 30 people, where you can periodically take them on a field trip," she says. "The question is, How do you connect 30,000 people? We figured if gaming can connect millions, let's try it."

Moritz agreed right off the bat. "This is the next generation's way of thinking," he says. Structured in three stages and lasting nine months, PowerPitch was open to any U.S. employee below the partner level. Says Moritz: "The only rule was you had to have a team; you couldn't do it by yourself." The task: Pitch a new line or a radical rethinking of an existing PwC service that could be worth $100 million in revenue.

To create buzz, PwC offered $100,000 for the victors, plus the chance to help implement the winning proposal. (When asked what the cash would mean to his team, finalist Ken Edwards, 53, a managing director in the San Jose advisory practice, answered like a true accountant: "Split six ways and after taxes, not that much. But the bigger thing is that your idea gets acted on.") PowerPitch generated a torrent of response. When Round 1 closed on Jan. 4, 779 proposals had been pitched. By the time of the July 28 finale, between direct participation, comments, suggestions, and votes, nearly 60% of the firm had participated.

Who will be the next accounting idol?

With nearly 800 ideas to consider, it was no small task to winnow the original proposals. But all PwC employees were encouraged to read the plans, offer suggestions, or critique them online for all to see, and then cast their votes. A panel of 194 partners selected 20 to advance to Round 2, with another five from the popular vote nabbing semifinal status as well.

PowerPitch's second round paired those 25 remaining teams with advisers -- one partner from within the industry that the idea focused on and one recently retired partner -- and granted each team 200 otherwise chargeable hours to work on their plans. Most spent significantly more than that. "It was an investment in time and money," notes Moritz, "but we needed to balance short-term costs against long-term sustainability. This is the kind of program that becomes a talent magnet." Just the leadership opportunities and career development for the junior employees, he says, justified the program. And if even one of the ideas actually becomes a $100 million line of service, it'll dwarf the costs of PwC's investment in PowerPitch.

Lou Testoni, 61, an assurance partner in Pittsburgh who retired last June after 37 years with PwC, coached Simply Stated, the dance-partying finalist team, which conceived a tool to simplify the creation of financial reporting documents for tax clients. Testoni helped the team identify the types of information and insight they'd need to bolster their idea, and then connected them with PwC executives who held the knowledge they needed. He argues that tapping retired partners offered an extra benefit: Team members aren't worried about looking stupid -- as they might in front of their bosses -- so they can ask better questions and learn more.

Testoni provided tough love when their final presentation "read like five different people had put it on paper," he says. "So we had a coaching session. I said, 'Okay, guys, you've got to make this look like one unified story, with one voice.' I offered my most critical review of their work, and they went back and did their homework and fixed it."

On July 11, five of the semifinalist teams were notified that they'd made the final cut and would fly to New York City to pitch their plans to the panel of judges, five of the firm's most senior executives. Mitra Best would emcee, and Bob Moritz would reveal the winner. In the two weeks before the finale, the finalists would be coached on public speaking, they'd write and rewrite their final business plans a dozen times, and they'd receive last-minute advice from their mentors. One group, led by 23-year-old Pia Ramchandani, was advised, "Don't just focus on the what, explain the why -- why do clients need this, why will someone buy this?" For many, this would be the first major presentation they'd ever delivered.

When July 28 rolled around, the nervous contestants' sweaty palms matched the day's steamy weather. The 220-person auditorium at PwC's headquarters was packed, and another 200 watched via closed-circuit TV in the cafeteria area. Outer offices held viewing parties, while others watched from their desks via live webcast, bringing the audience into the thousands.

Capozzi kicked things off, coolly delivering his team's pitch for a new "technology agnostic" predictive analytics service. The judges peppered the team: "What exactly are clients buying?" asked judge and tax leader Rick Stamm. (A service, not software.) "Which industry is your focus?" asked advisory leader Dana McIlwain. (Health care and financial services.) "Is this about taking market share away from others or mining an opportunity not currently used?" queried vice chairman Mitch Cohen. (The latter.)

Next up was Simply Stated, who shared the four-minute spotlight equally among its six members. "I know we're the only ones who did that," says team member Danielle Signorelli, 24, "and I think it made us stand out." Judges wanted to know: Have you thought to partner with outside companies? Do the people who would license this fit our brand? Team leader Alexis Zakroff, 26, delivered the line of the day when she responded, "We plan to target young, dynamic, growing companies who are future Fortune 500 companies. Kind of like the young, dynamic talent here today."

A team pitching a different analytics service targeted to "big-bet decision-making" took the stage third. This group comprised employees from Diamond Management & Technology Consultants, a smaller firm acquired by PwC just a month after PowerPitch was announced. Team leader Ramchandani says the group had cultivated the concept at Diamond but "didn't have the resources there to fully invest in this. So when we got acquired and PowerPitch was announced, it was perfect."

After the five finalists had made their presentations, the judges huddled, taking just eight minutes to tally their scores and wrestle briefly between two teams. Moritz announced the winner. "These results are certified by PricewaterhouseCoopers," he said with a wry smile, then awarded the $100,000 grand prize to Capozzi's team for its concept, which would create a sophisticated data-mining practice that can employ the sorts of analytics that, say, Netflix uses to determine which movies each customer wants to see, for clients that don't have those resources in-house. Meanwhile, the four runner-up teams each received a surprise $25,000 bonus, and the 20 semifinalists who didn't make the finale split $5,000 per team.

Since then, each of the final ideas has been assigned to a senior "champion," who will work with the teams to develop and launch the plans. PwC had initially planned to back just the winner but has since decided all five are worth investing in. And in an effort to avoid what Cohen calls "Jennifer Hudson syndrome," where stars who didn't make the finals get overlooked despite having tremendous market potential, all 20 of the concepts that made the semifinals will be assigned to an incubation group.

PwC's leadership now refers to PowerPitch as a "program" that will be repeated in the future. The biggest question is when: With so many ideas to incubate and develop, PwC may not be able to handle the results of another competition next year. Of course, having too many ideas is the best kind of problem to have.

--Alison Overholt is a former writer and editor at Fast Company and ESPN The Magazine.

This article is from the October 17, 2011 issue of Fortune. ![]()