They don't have college degrees. They have few job prospects. They feel left behind.

Nearly one-quarter of white men with only a high school diploma aren't working. Many of these men, age 25 to 64, aren't just unemployed ... they aren't even looking for a job, according to federal data.

Their college-educated peers, however, have fared much better. Only about one in 10 isn't working.

The plight of these blue collar workers is now in the national spotlight. The 2016 presidential election has awakened their political power and reshaped the course of the campaign.

Their anger -- which has brought millions to the polls, particularly on the Republican side -- has prompted the candidates to focus heavily on manufacturing, trade and other issues of importance to this slice of America. Four years ago, the GOP nominee Mitt Romney dismissed the 47% of Americans who don't pay taxes. Now, frontrunner Donald Trump proclaims that he loves "the poorly educated."

Related: Just how much better off are college grads anyway?

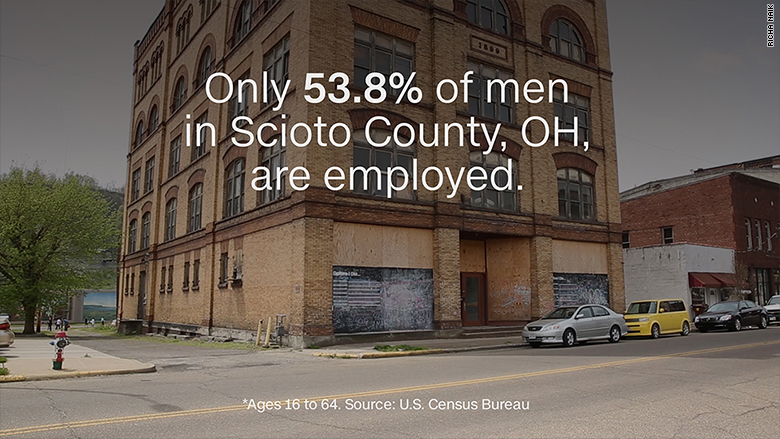

CNNMoney went in search of these men who feel forgotten by both Washington and the economy. It brought us to Scioto County, a stretch of Appalachia in southern Ohio just across the river from Kentucky, where only 53.8% of men age 16 to 64 are employed. While Ohio Governor John Kasich won the state, Trump was heavily favored in these parts.

It's tough to make a living in Scioto County these days. Gone are all but one of the shoe manufacturing factories that used to employ thousands. Shuttered are most of the steel mills that supported middle class families. Shrunken are the railroad maintenance yards that once carried coal from Kentucky and paid well.

The unemployment rate -- those who are out of work but actively looking for a job -- stood at 9.2% in February. The poverty rate is 27.2%, far above the state's 15.8% rate.

The layoffs are continuing. AK Steel let go of about 600 people a few months ago. CSX and Norfolk Southern railroads have downsized over the past year. Haverhill Chemical laid off more than 150 workers in August after new owners bought it and hired only some back.

Some of the Haverhill workers made $35 an hour, a wage "you just don't replace in this area," said Luanne Valentine, who oversees the OhioMeansJobs center in Scioto County, which has about 77,000 residents.

Related: Massacre rattles rural, Ohio community, where 'everybody's hurting'

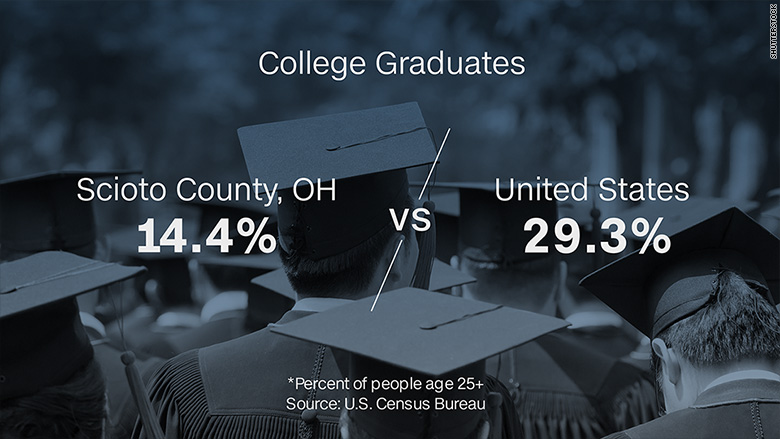

One of the main problems: Many residents don't have the education or training to make it in today's economy. Only 14.4% have a college degree, compared to 25.6% statewide and 29.3% nationally.

A generation ago, Scioto residents didn't need to go to college to earn a decent wage.

"Thirty to 40 years ago, a man had a job at a shoe factory. His wife didn't work. They were able to raise a couple of kids," said Steve Sturgill, executive director of Community Action, which provides workforce and social support services for local residents. "That's not the case today."

Sure, there are some jobs available. But many of them pay minimum wage or just above. Local officials are trying to attract more employers, but the new positions often don't pay as much.

Paul Brown, 28, has worked his share of factory jobs in southern Ohio and in his hometown of Knoxville, Tenn., but most of them paid poorly. Brown, who earned his GED in 2007, bounced around, serving short stints at a landscaping products manufacturer, a plastics factory, an auto parts supplier and a truck assembly plant. Many of the positions were temporary, and he earned no more than $13.84 an hour for "very repetitive, strenuous work." There was little path to move up in pay or responsibility.

The Waverly, Ohio, resident doesn't see how one can support a family with a blue collar job today. He works as a service technician for a garage door company, earning $11 an hour. He's thankful to have work: It allows him to get by -- although living with relatives helps -- and send money to his two children from previous relationships. However, he says he couldn't afford to get married and raise a family.

Brown wants more than a dead-end job, but employers don't give people like him a chance to show them what he is capable of, he said.

"In Southern Ohio, job opportunities are slim to none unless you have a college degree or some type of training," said Brown, who is now studying to be an electrician in hopes of jump starting his career. "Even with those, it's hard."

Related: U.S. has lost 5 million manufacturing jobs since 2000

A family of four in Scioto County could have a nice, middle class life making $25 an hour, but to earn that much, both parents usually have to work, Sturgill said.

This dour economic reality has left many young adults struggling to make their way and older, displaced workers unable to regain their footing, Sturgill said. Federal funds to train them into new careers have dried up.

How do people cope? Those with skills and options have left town, moving to Columbus or Cincinnati (both about 90 to 100 miles away) -- or even further. Among those who remain, drug addiction is rampant. Nearly 5% of county residents are on disability, compared to 3.1% statewide. Others work multiple minimum wage jobs or off the books to make do in a job market that's passed them by.

Michael Cavins is one blue collar resident who feels left behind.

Growing up in rural Kentucky, where his family had to draw water from a stream at times, Cavins, 44, figured he'd follow his father and uncle into the coal mines. But by the time he graduated high school in 1990, the mines were shutting down. So he wound up working in factories in nearby Ohio, first inspecting truck doors for M&J Industries and then building kitchen cabinets at Mill's Pride. The pay wasn't great -- $12.75 an hour -- and he had to drive nearly an hour to the plant, but it allowed him to support a wife and two kids in Wheelersburg, Ohio. (He also has three older children from a previous marriage.)

Mill's Pride, however, shut its doors about five years ago, laying off about 1,400 people. When he found out the factory was closing, Cavins found a job at a pest control company, but had to quit a few years later after developing health problems.

Cavins has been on disability since 2014, when he was diagnosed with leukemia. His wife, who has thyroid cancer, is also on disability, leaving them struggling to pay the bills every month. They receive food stamps and are on Medicaid.

"My high school diploma took me as far as it could take me," said Cavins, who hasn't been able to find a decent-paying job. "I feel like I've been pushed aside. Everything is disappearing ... all the factory work is going overseas. If they keep sending it everywhere else, how are we supposed to survive?"

Related: $75 a day vs. $75,000 a year: How we lost jobs to Mexico

Cavins, who didn't vote in the primary but likes what Trump has to say about bringing factory jobs back to the U.S., thinks companies should manufacture more domestically and not just look for the cheapest place to produce their goods. That would help both Americans and the economy. But, he acknowledges it will take a lot of work.

Meanwhile, unlike some of his fellow factory workers, Cavins is determined to get a good job. He's betting that a yearlong course in industrial maintenance will give him the skills needed to work in heating and cooling services, which his online searches found can start at $40,000 a year. He's willing to leave Scioto County and work anywhere ... in a hospital, factory, school or water supply facility, for instance. One day, he'd like to start his own business.

The program, offered at Scioto County Career Technical Center, costs nearly $10,000 and has placed 95% of its graduates over the past two years in jobs that typically earn between $31,000 and $40,000 annually. To finance it, Cavins received a federal Pell Grant for $5,900 and took out two loans.

"I didn't think I'd get anywhere without learning a trade," said Cavins, who graduates in September. "I want to give my family better than what I had. I want to try to break the cycle and not live on disability."