The World Cup is coming to North America in 2026, and the 23 cities competing to host games are optimistic that the tourism and exposure will boost their economies.

But others are sitting out, warning that past tournaments have done more harm than good.

Brazil's 2014 World Cup, which cost $15 billion to host, provides a cautionary tale.

"An incredibly expensive boondoggle," said Brian Winter, vice president of policy at Americas Society/Council of the Americas. "All the promises went up in smoke."

Plans to invest in bullet trains and build new airports lingered while the country pumped cash into grand stadiums in hopes of creating economic opportunities.

But Ludovic Subran, chief economist at Euler Hermes, said that wasn't a realistic hope. "It's like building a stadium in the Rust Belt and saying it'll boost the economy. It won't."

Some of the stadiums were constructed in obscure places -- like Manaus, in the Amazon rainforest -- which beyond hosting a few World Cup matches had limited use.

Brazil's economy was in bad shape before the games arrived because private debt and inflation were increasing, said Edward Glossop, an emerging markets economist at Capital Economics.

The country entered a recession the same year. Hosting the Cup didn't save it, but may have contributed to its decline.

Managing big costs

Keeping infrastructure costs low is key to hosting an economically successful games, said Victor Matheson, a professor of economics at College of the Holy Cross and contributor to the web site FiveThirtyEight.

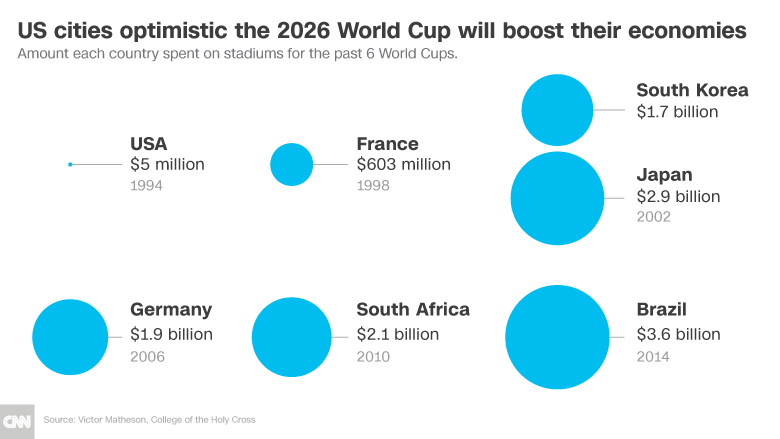

The 1994 World Cup in the United States achieved better economic results than the five more recent ones, Matheson said. It spent only $5 million on stadiums, compared with Brazil's $3.6 billion.

The 2026 games should follow the '94 example.

Fifteen of the 17 proposed American stadiums are already home to NFL teams. For the Cup, they may need tweaks, but Matheson said the newer NFL stadiums were specifically designed to also host soccer.

"No major public expenditures [are] required to stage a successful and memorable competition," according to the US Soccer bid book. It predicts that the event will generate more than $5 billion in short-term economic activity.

Still, FIFA has a reputation of stubbornness. Chicago decided to withdraw from the 2026 bid after FIFA demanded that a dome be built over its Soldier Field stadium.

"FIFA's inflexibility and unwillingness to negotiate were clear indications that further pursuit of the bid wasn't in Chicago's best interests," said a spokesman for Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

FIFA did not respond to a request for comment.

Tourism

Miami mayor Carlos Gimenez, on the other hand, is optimistic.

He thinks the World Cup might plug a tourism gap during Miami's low season.

"It would have a tremendous economic boost," he said. "It's like the Super Bowl on steroids."

Miami will host its 11th Super Bowl in 2020, and the mayor expects it'll produce a boost of $200 to $400 million. Gimenez said four World Cup matches would equate to four times that economic lift.

But the net tourism benefit is historically modest, according to Andrew Zimbalist, the author of "Circus Maximus: The Economic Gamble Behind Hosting the Olympics and the World Cup." Zimbalist said the "skedaddle effect" offsets revenue from tourists because residents leave to avoid the commotion.

Some cities will benefit more than others, according to Zimbalist. New York is usually a tourist mecca in the summer months, but if the Big Apple is not chosen to host, would-be visitors may head to another city to catch some soccer action.

Meanwhile, Boston may see tourism spike if Gillette Stadium is selected, for instance.

The worst-performing city at USA '94 was Orlando, because soccer took tourism dollars away from theme parks, according to Matheson.

Related: A World Cup in the United States is a huge win for Fox

Media Exposure

Harder to measure is the increased global exposure. Dallas was a host city in 1994, and Bobby Abtahi, the city's Parks and Recreation board president, believes the publicity bolstered the city's reputation.

"It broke a lot of misconceptions," said Abtahi. "We've become a truly international city since then."

According to Winter, success is a matter of perception.

"Let's stop pretending that it's for anything else than throwing a huge party," he said. "And that's OK."