This story, like so many involving global trade, starts in China.

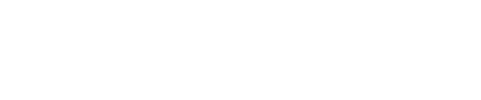

There is a big market for the totoaba fish in China -- a demand that can be traced back to traditional Chinese medicine. Dried fish bladders are believed to be aphrodisiacs and have various health benefits. The Mexican totoaba, a fish similar to a sea bass, has a large bladder that is highly coveted among Chinese elite.

And the totoaba can be found only in a small area of ocean in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez, near the town of San Felipe, 120 miles south of the US border.

High demand for a commodity often breeds corruption. That’s what demand for the totoaba did in San Felipe.

That corruption was exposed one morning in 2014. Samuel Gallardo was taking a stroll with his family along the shore near San Felipe, when someone in a passing vehicle shot and killed him. Neighbors and local fishermen later revealed that that Gallardo had been well-connected in the powerful Sinaloa cartel.

But Gallardo had started a new venture. He and a handful of locals had been using their know-how in narcotics trafficking to transport totoaba bladders across the US border and eventually to China. Gallardo’s murder signaled the end of the secret. He had tapped into a multi-million dollar business, and now everyone wanted a piece of the action.

After Gallardo’s murder, local fishermen realized they were sitting on a gold mine. On a typical day, fishermen were able to make between $5 and $10 per kilogram (2.2 lbs) of shrimp. A kilogram of totoaba bladder can sell for up to $8,000 in Mexico; a whole bladder can sell for up to $250,000 once it reaches China. Totoaba bladder prices can vary significantly depending on the size, age and quality.

Soon, the totoaba was being harvested by local fisherman and organized crime networks.

According to a Mexican Army official, organized crime arrived with “established networks, routes, contacts, outlets, and sponsors.”

Compared to narcotics, a totoaba bladder was a low-risk, high-reward product -- similar in value to cocaine. The totoaba’s protected status made it illegal to fish, but the waters in San Felipe were sparsely patrolled. Authorities at border crossings in Mexico, the US and China had been largely unaware of what a bladder looked like, and for a few years, they flowed freely.

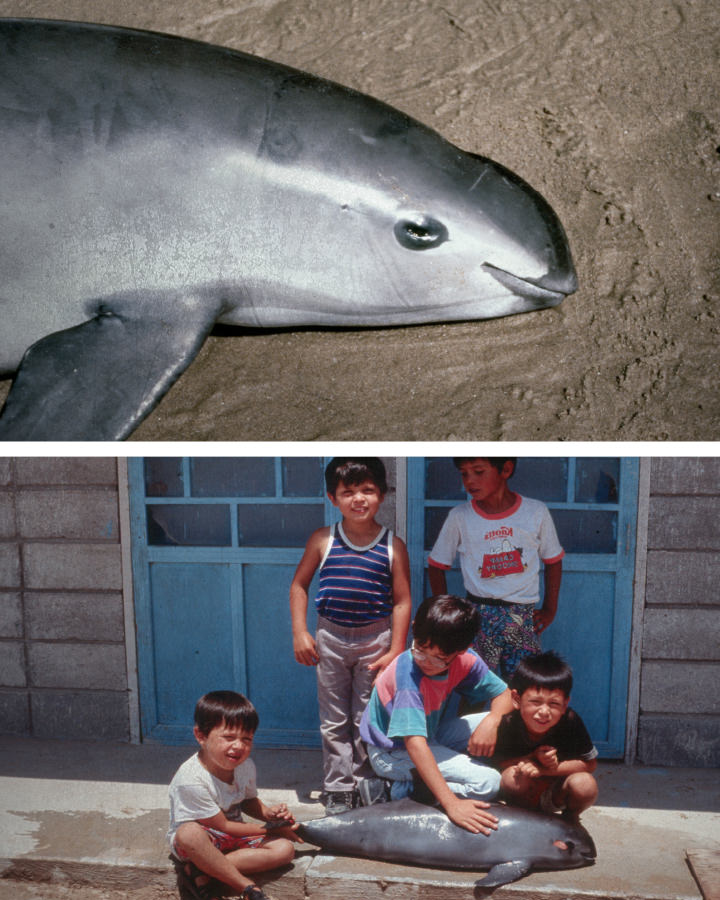

In San Felipe, the influx of money was hard to miss. Fishermen who once earned $500 a month were driving Italian sports cars. Teenagers were making over $20,000 in one night of fishing, and many would flaunt their cash on social media. Bars were packed every night, and a feeling of never-ending wealth filled the streets.

Then everything came crashing down.