Updated Status: It’s complicated

Once arm’s length from anything editorial, tech CEOs are realizing they can no longer be neutral when it comes to content on their platforms. Where’s the line between a difference of opinion and straight-up lies -- and who should make those decisions?

“You get into an area where most companies would be like, ‘It’s not something that really fits our model or that we would even be good at,’” said Williams. But increasingly, there’s little choice.

Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince described the nuance when he made the decision to kick neo-Nazi site The Daily Stormer off his platform, which helps protect websites from online attacks.

He put it flippantly in a memo to employees: He woke up one day and decided someone shouldn’t be allowed on the Internet. He worries about that power, and so should you.

In today's polarized climate, that power can be viewed as politically motivated, according to Prager University CEO Marissa Streit.

Prager University isn’t an actual academic institution. It was founded by divisive radio host and conservative commentator Dennis Prager and produces online videos for YouTube -- the segments tend to promote conservative ideology.

“Our topics are ideological in nature,” Streit said. “We do pro-America. We believe in economic freedom.”

This includes videos like "How to Raise Kids Who Are Smart About Money" and "Did FDR End the Great Depression?" -- but it also includes some more controversial content, like “Are 1 in 5 Women Raped at College?” and “Gender Identity -- Why All the Confusion?”

Behind the scenes at Prager U’s Los Angeles studios

Streit noticed some of the content -- including the latter two videos -- was being categorized as “restricted” on YouTube, which is a setting for “potentially mature” content. This makes it more difficult to find the videos in a search.

The group has 250 videos -- around 30 of which have been restricted by YouTube. Streit said she was frustrated by the lack of transparency.

“We kept going back to them, [saying], ‘There's no pornography in our videos.’ We've always been very clear about our mission," she said. "We do know that we present a certain ideology that may or may not agree with everyone. The question is: Is Google the one who gets to decide what everybody gets to watch?”

When asked about PragerU, Google responded broadly in a statement: "Giving viewers the choice to opt in to a more restricted experience is not censorship. In fact, this is exactly the type of tool that Congress has encouraged online”

Prince saw the lack of transparency play out on the other side.

“We could have done it differently. We could have just said, ‘They violated section 13G of our terms of service…and swept it under the rug,’” Prince said, regarding his decision to kick off The Daily Stormer. “It would be BS if we did it, and it’s BS when any other technology company does it. That’s the point that is important: There are arbitrary decisions that get made.”

Streit and Prince aren't alone in worrying that tech companies have too much power over what people see and who has a voice on their platforms.

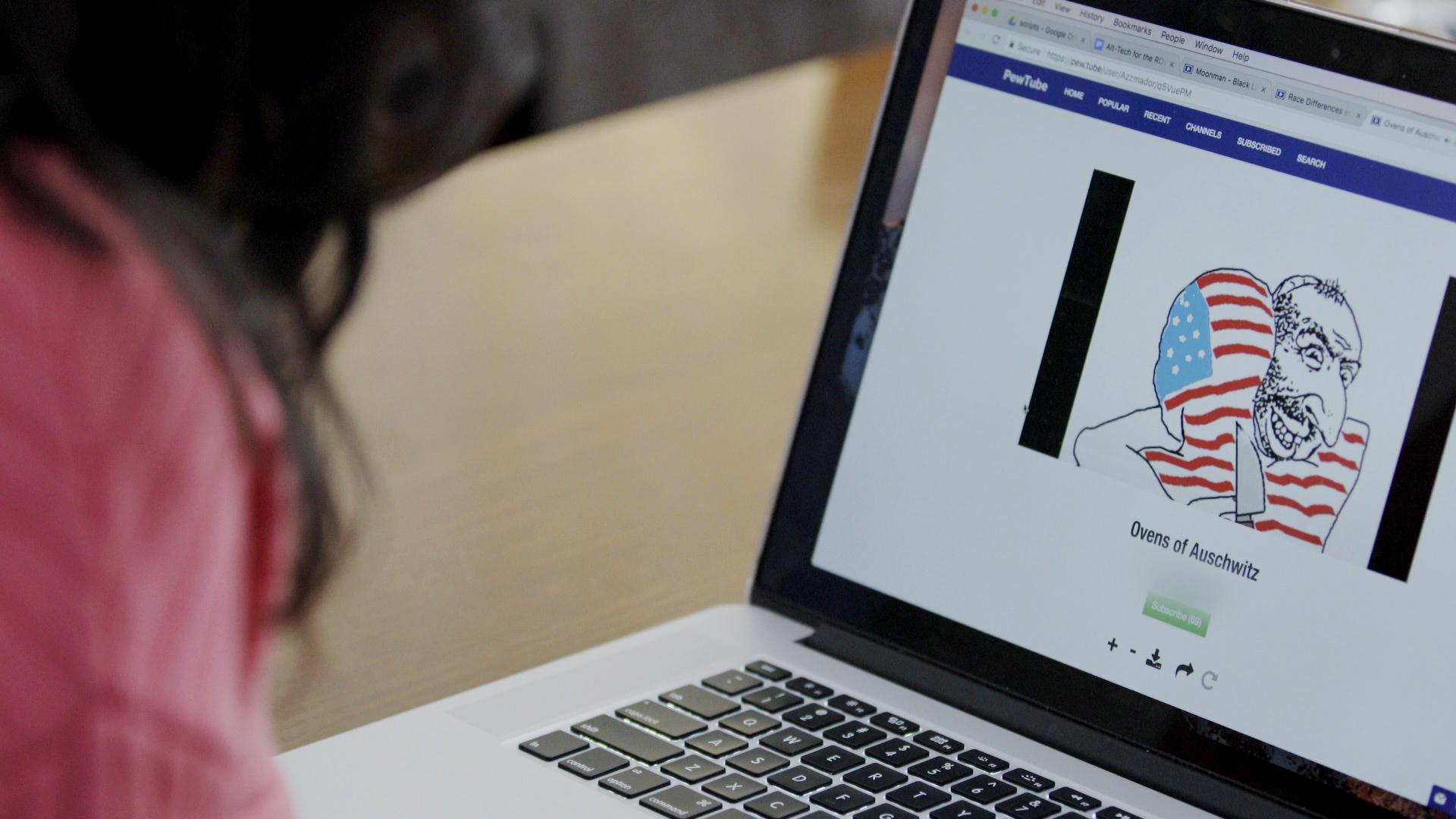

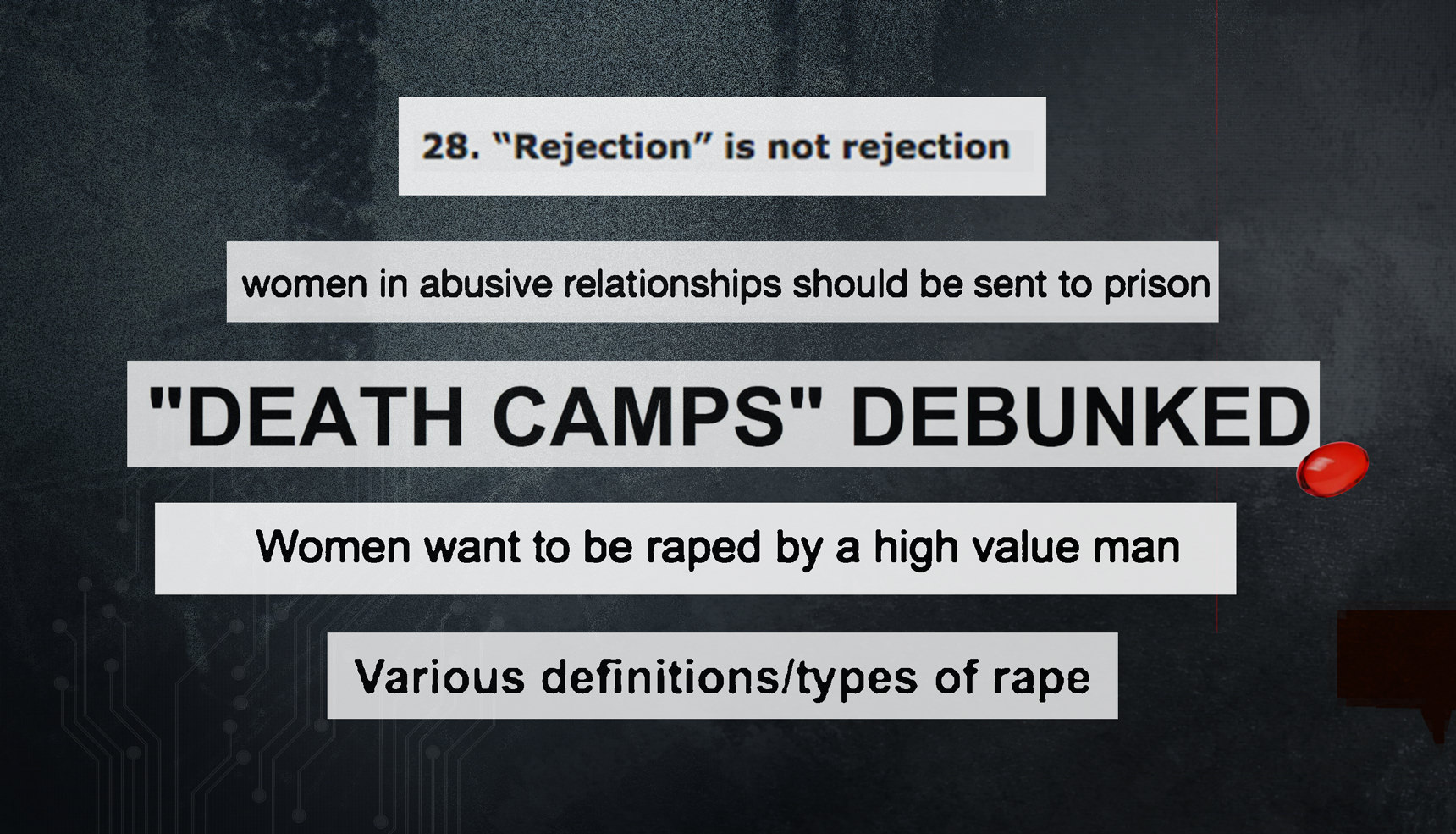

In response, a number of alternative platforms have sprung up. Sites like Hatreon, PewTube and Gab cater to controversial, far-right figures, many of whom were kicked off more traditional sites like Patreon, YouTube and Twitter. These platforms are small and may have limited influence, but they're building communities for people who explicitly reject Silicon Valley's influence. The founders champion free speech, but their platforms give a voice to some of the ugliest ideologies.

“What we’re seeing with [social media] platforms is a monopolization of control over commerce on the Internet,” said Barry Lynn, executive director of the Open Markets Institutes. “When you have this much power in these few hands, then you're going to have problems. Not only might they take this information and manipulate the flow for their own political good, they're also just sloppy about it. They just don't do a good job of managing the process.”

“Right now, conservatives are the underdog in Silicon Valley.”

Harmeet Dhillon, James Damore’s attorney

The irony isn’t lost: A place that promised to unite us, to connect the world, is suffering from its own massive divisions. In the current political climate, you could argue the tech built in Silicon Valley is pulling us into our own filter bubbles, with algorithms that only reinforce our beliefs. Meanwhile, behind closed doors, conservatives in tech are forming an underground community. I spoke to a number of entrepreneurs who identify as conservative but keep it a tightly held secret. Being conservative in tech, they say, is enough to threaten their jobs.

Aaron Ginn founded Lincoln Network, a community for conservatives and libertarians. He said if you’re conservative in Silicon Valley -- whether or not you voted for Trump -- you're often perceived as racist or homophobic.

"The fact is that if you have any center right view, you're automatically put in that camp now," he said.

Aaron Ginn founded Lincoln Network, a community for conservatives and libertarians in tech

And as Silicon Valley deals with scrutiny over a lack of gender and racial diversity, there’s a rather unexpected group that feels underrepresented: wealthy, white, conservative males. Former Google engineer James Damore wrote a controversial memo over the summer, criticizing Google's lack of ideological diversity and arguing that “biological” reasons hold back the number of women working in tech. He became a touchpoint in Silicon Valley's culture wars -- standing in for all the men who feel oppressed by tech's professed liberal values.

Damore hired Harmeet Dhillon, a civil rights attorney, who said she’s now representing those people. “I've always had a penchant for the underdog and right now, conservatives are the underdog in Silicon Valley.”

Sexual Harassment: 'That’s Just Life in Silicon Valley'

When you look at everything festering just below the surface, when you see how misogyny and sexist rhetoric have been exacerbated and amplified on sites like Twitter and Reddit, it's not hard to see how Silicon Valley itself has been hit by widespread allegations of sexual harassment and discrimination.

Susan Fowler's eye-opening account of sexual harassment at Uber was only the beginning. Reports in the New York Times, The Information and a CNN Special highlight the countless instances of bad behavior in the tech industry. While tech leaders are getting better at responding to overt harassment, deep-rooted issues of sexism are still all too present.

But what is changing is the movement of women starting to come forward. One of those women, Elizabeth Scott, filed a lawsuit against influential virtual reality startup UploadVR, alleging gender discrimination, harassment and a hostile work environment.

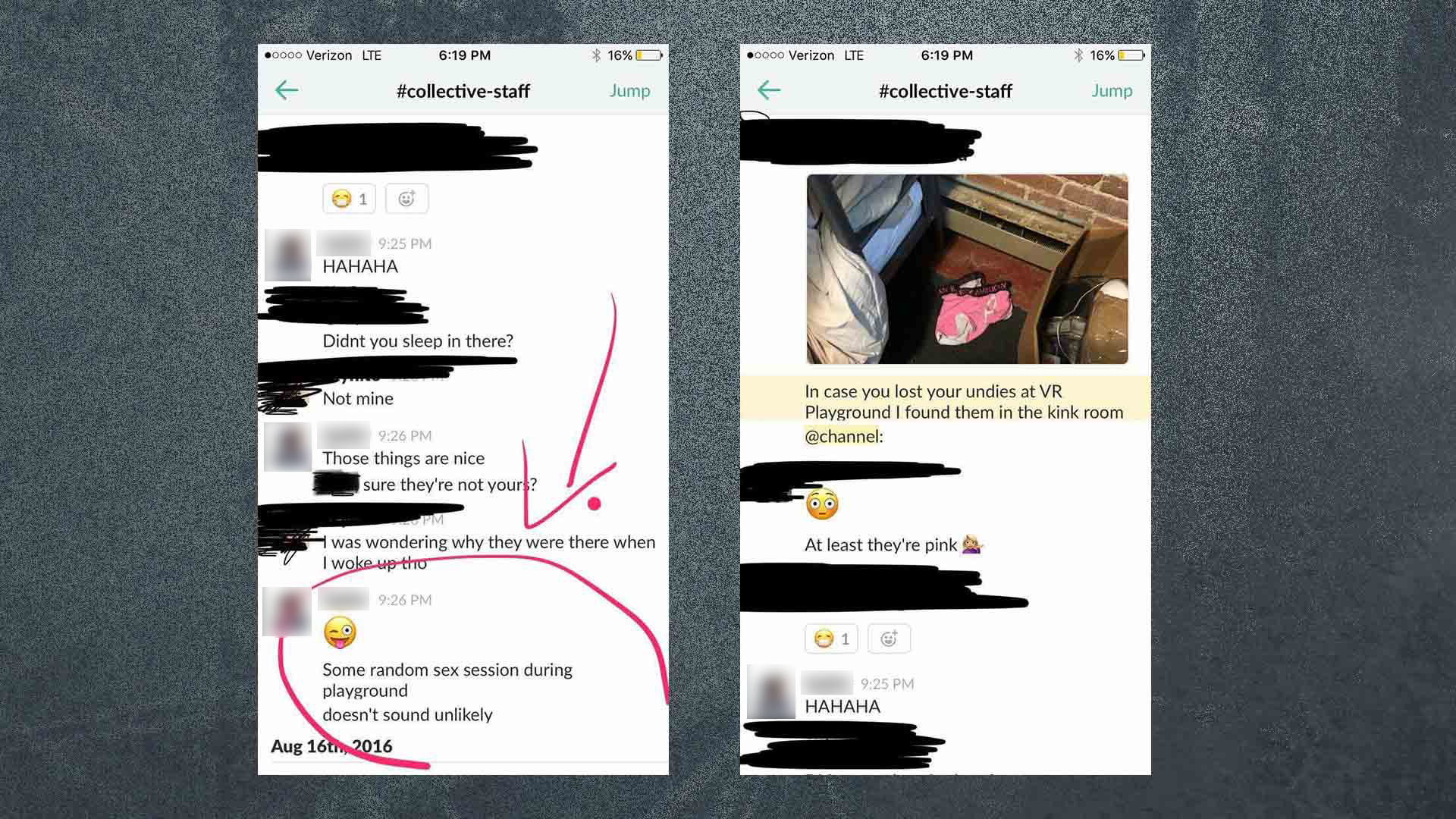

The suit paints a picture of a company rife with immaturity and sexism. While Scott settled and is unable to talk about the details of the lawsuit, another former employee, Daisy Berns, spoke to CNN Tech publicly for the first time. A former general manager at UploadVR, Berns recounts a party culture where the lines between employer and employee blurred, and women at the company were tasked with cleaning duties. For Berns, that meant picking up underwear left on the floor from “office” parties thrown by the founders.

The Upload founders acknowledge that the bulk of the cleaning duties often fell to women -- but said that was due to the functions of those women's jobs.

"When you run a space that has events and is a co-working space, you have to have people that are tasked with maintaining that space at all times," said Taylor Freeman, one of the cofounders. "Those two people, our events producer and our office manager, were both women. Ultimately, it's just unfortunate that our office manager at the time had to deal with finding some of these things."

Freeman acknowledged that the atmosphere in the company's early days lacked professionalism but chalked it up to their relative lack of experience -- he was 23 when he started Upload (his cofounder Will Mason was 24).

"We never intended to do anything wrong or to put women in a position where they felt out of power or like they weren't being heard," he said. "We really didn't have the experience to create a culture [and] the structure where they had a voice."

Freeman and Mason took responsibility for enabling the environment. They said the company has since built an HR structure, stopped its party culture and hired executives to help take the company forward.

But it hasn't been a smooth process. Anne Ward, one of the executives hired to help the company, stepped down after four months, citing an overarching lack of respect.

"The tone from the top needs to change," she said.

Scott, meanwhile, suffered ramifications for speaking out. After multiple interviews, another tech company informed her they couldn’t hire her -- she was a liability.

Many other women told me they couldn’t share their stories about UploadVR publicly for fear of retribution.

We protected the identity of conservatives in Silicon Valley who said their bottom line would be impacted if they were “outed,” but women in tech are wondering how they can speak out without their job prospects taking a hit.

It’s 2017, and sexual harassment in Silicon Valley is still running rampant. The question being asked in the internal message boards for women in tech -- now what?

Scott, who felt powerless, said the 20-page lawsuit is her voice.

“It makes it real to see it in writing,” she said. “There is power in speaking up, even if not everybody believes you.” ■

This story published on October 29, 2017