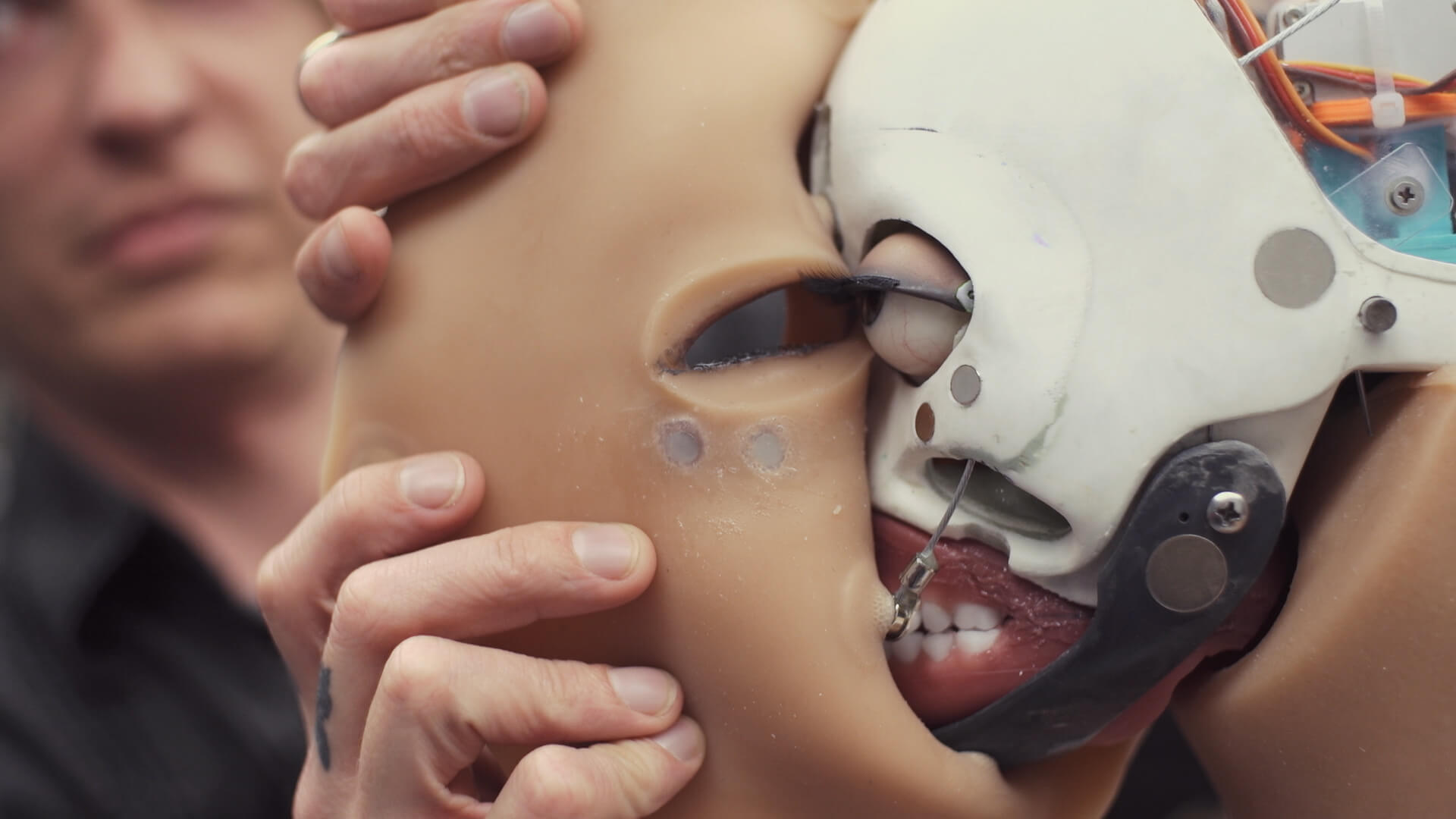

The dolls have a removable apparatus that enables clients to have sex with them. It's dishwasher safe. McMullen prefers you refer to his dolls as "love dolls." Sex is too simple, he says. "

A lot of our clients tend to have feelings that are beyond sexual desires. So they actually become attached to their dolls. I think love is a little more in line with what it is."

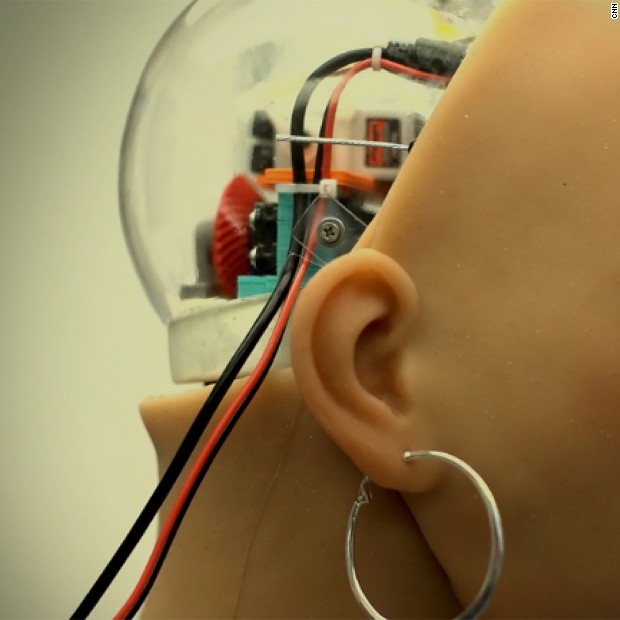

McMullen, like Lilly, insists that human connection isn't required for happiness. And he's tapped into a niche market that feels the same way. But his efforts open the door for even more complicated questions. Having built human-like dolls, he now wants to bring them to life using artificial intelligence.

With a team of engineers, McMullen is building "Harmony," an app that lets users design their own highly customizable girlfriend. They can pick over 300 combinations -- from body type all the way down to ear size. Users will also be able to program her personality: a couple clicks and she can be quiet, moody, kind, innocent or intellectual.

The goal, McMullen says, is to create more "intimate" artificial intelligence.

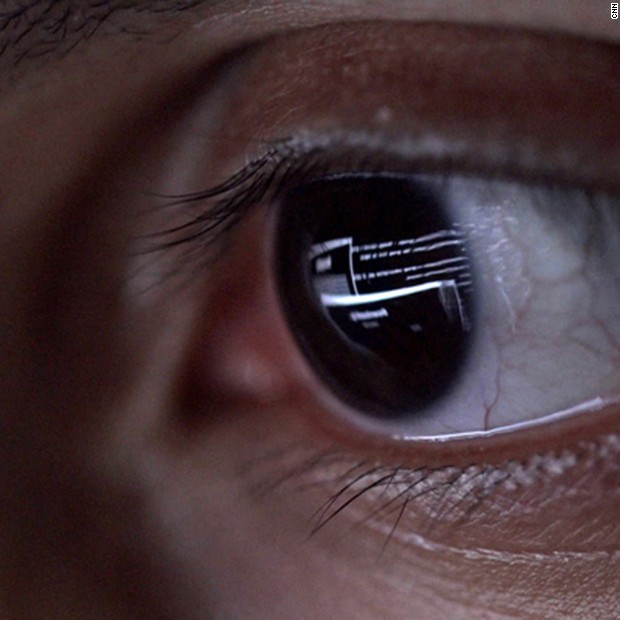

"Siri doesn't care when your birthday is or what your favorite food is or where you were born or where you grew up," McMullen explains. "Our AI, on the other hand, is very interested to know who you are."

Harmony will know what you're afraid of. She'll know your favorite food.

"When you get to know a person, they remember certain things about you. That's how you start to perceive that they care about you, that you have a mutual knowledge of each other," he explains.

The app, which will go live this month, will cost $20. Connect it to the Real Doll and you've got a robotic girlfriend in a lifelike form. The total cost is around $15,000.

Arkin warns about building these types of relationships with robots who appear as though they care.

"We create the illusion of life in these particular systems, so that is fundamentally a deception," he says. "This danger [is that] you fall in love with the robot, but the robot doesn't care at all -- it's got no feelings, it doesn't really have emotions."