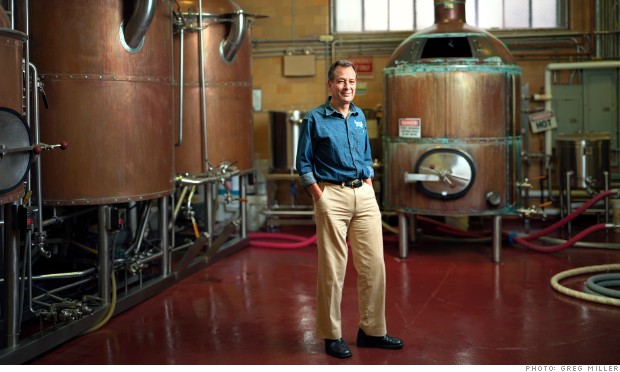

Jim Koch at Sam Adams's Boston brewery

I grew up outside Cincinnati on a farm where I spent a lot of my summers. My dad was a brewmaster, and my mother was a teacher. When my dad's company went out of business in the late '50s, he started a company for brewing supplies. I come from a long line of brewmasters, so I grew up with beer and entrepreneurial instincts.

I went to Harvard and majored in government. But when I graduated in 1971, I didn't know what I wanted to do. So I went into Harvard's JD/MBA program and dropped out after two years. I did a variety of jobs, including being an Outward Bound instructor, then went back to Harvard and finished the program in 1978. I decided not to take the bar, and I went to work for Boston Consulting Group [BCG] in 1978.

There I did strategy consulting for manufacturing. It was an opportunity to see business from a high-level perspective because we worked for CEOs and senior management in sizable companies. But after six years I started to think about what else I wanted to do.

I just wasn't comfortable with the big company culture, bureaucracy, and politics. I wanted to stand on my own two feet and accomplishments rather than succeed in an organizational context. I quickly settled on beer. It was like destiny.

In 1983 there were no craft beers or microbrewery success stories. I thought, I can start my own brewery, which hadn't been done in the U.S. in decades. Small-scale, startup brewing died out because of the expense. So I took $100,000 in savings, got a second mortgage, and raised $140,000 from friends and family.

MORE: The new United States of Booze

When I told my dad I wanted to start a brewery, his reaction was, "Jim, you've done some stupid things before. This is about the dumbest." In his lifetime, breweries went out of business, and in his world, the little guy was bankrupted by the big guys. But my dad gave me his course materials from brewmaster school, and my education was state-of-the-art 1948. We've learned to make beer cheaper and faster since then, but not really better, so I don't think I missed much.

The recipe for Samuel Adams Boston Lager, our original flagship, is an old family one. I'd home-brewed before, so I brought test batches to BCG and had people taste them while I was thinking the idea through. I left the company at the end of 1984.

My first hire was the best I ever made: a woman named Rhonda Kallman who had worked at BCG as a secretary. She was 23, organized, very outgoing, and had worked as a bartender at night. For the first six months we had no office, desk, computer, or telephone. [She eventually managed sales and brand development before leaving in 2000.] We were focused on brewing the beer and working our butts off to sell it. Because there was no overhead, we were cash flow positive from the first month.

MORE: How Big Beer is taking on craft brewers

The recipe was traditional, and we needed some traditional equipment that some breweries no longer had. So for 3 1⁄2 years I'd fly on People Express -- where I paid for my ticket on the plane -- to use a brewery in Pittsburgh where I oversaw the brewing.

None of the distributors in Boston would deliver it because they were happy with the beers they already had. So we'd distribute it with a truck that I rented, and we did all the sales ourselves. I'd go from bar to bar, telling my story, educating people about quality in brewing and ingredients, and get them to taste the beer. Back then people thought the only good beer was imported. Here I was, making something that blew up that preconception. My beer was significantly more expensive, and people would say, "I can get Heineken for $14 a case, and you're charging me $20 for a domestic beer?"

I wanted an assertively American name, and Samuel Adams was a brewer, a patriot, and a revolutionary, so we named the beer after him. I wanted to create a beer revolution in the United States in the same way Samuel Adams created a political revolution. Our Boston Lager was the first time America had tasted rich, flavorful, fresh beer. Domestic beers were fresh but not flavorful, so it was a revelation to people. It didn't taste like Heineken, Corona, or Bud Light. Six weeks after it came out, we got picked at the Great American Beer Festival as the best beer in America.

MORE: Energy drinks brace for caffeine crash

The first year, we made around a million dollars, three times what we'd planned to make. At the end of our first year we had an office in an empty attic in an old house above the Back Bay in Boston. My desk was a sheet of plywood above an old claw-foot bathtub.

We grew, one bar at a time. We expanded through New England, then I flew to D.C., selling Samuel Adams to bars two days a week in 1986, using Presidential Airlines. I flew so much on them that they started selling Samuel Adams on their planes, and I got Samuel Adams printed on the back of the ticket jackets. It was all guerrilla marketing. The big guys were so big, we had to do innovative things like that.

Very early on I wanted to build a brewery in Boston but underestimated the cost. I ended up without a brewery and had to write off $3 million. It was a painful write-off, but I learned about designing and engineering a large construction project. In 1988 we opened our first brewery in Boston, and things just grew.

In November 1995 we went public. I had a lot of investors who were friends and family who'd had money in the company for 10 years and hadn't seen a return, and this was a way to do that and still keep control of the company. There are two classes of stock, and I have all the voting shares, which gives me the ability to manage and grow the company as I think is right. It enables me to make decisions based on the long term rather than quarterly returns.

MORE: What would a legal American marijuana industry look like?

We worry about survival and taking care of our customers, but we're not Budweiser. For the big guys, everything out there is taking away from your market share. In 1996, after we went public, Anheuser-Busch (BUD) mounted a full-scale attack campaign against us. There were negative ads saying our beer wasn't all made in Boston and that I was a fraud. Our revenue then was about $100 million, so we were doing well and perceived as a threat, even though Anheuser-Busch had 50% of the market at that point, and I was invisible. I had to go to the Better Business Bureau, and I got a cease-and-desist ruling from the Advertising Self-Regulatory Council in 1997 to stop the ads.

Today there are 2,400 microbreweries in the United States, and craft beer makes up 6% of the U.S. beer market. Our real competition is the imports. I never thought I was competing with Bud Light or Miller Lite. Today, after 29 years, we've finally reached 1% of the U.S. beer market.

Business has grown by double digits through the Great Recession. There's this growth in the appreciation of good beer, and people see Samuel Adams as an affordable luxury.

We have a roll-up-your-sleeves, no bureaucracy, get-it-done company culture. Tomorrow I'm going to work the northern New Jersey market with my salespeople, calling on accounts and selling beer. I was at our brewery in Ohio last week, working with people there. Moving forward, I'm just focused on making great beer and working hard to sell it. If we can get great beer into the mouths of our consumers, we'll do just fine.

My Advice

Know the market. Is your product better or cheaper than the alternatives? If it's not better or cheaper than what's already out there, you don't have a real business to build on.

Don't hire people unless they raise the average. We've profiled successful people in our company and have developed interview questions to determine whether a candidate has the same motivational needs and behavioral attributes that have made others successful in that particular position. You don't want someone who's just good enough for the job. You want to raise the average.

Learn to fail quickly. We've had dozens of beers that were not commercially successful. Minimize the damage, know when to pull the plug, and move on.

This story is from the April 8, 2013 issue of Fortune. ![]()