Over the course of a few months, a debt collector you’ve probably never heard of spends more money wooing politicians than most Americans earn in a year.

Linebarger Goggan Blair & Sampson has countless politicians -- from school board members to state lawmakers -- on its side. It takes them to fancy dinners and spends millions on their campaigns. It even puts current elected officials on its payroll.

These connections have paid off big time. For decades, the firm has beat out the competition, gotten some state and federal laws changed in its favor and landed lucrative contracts nationwide -- making it one of the favorite debt collectors for state and local governments across the country.

And nowhere is its political pull greater than in its home state of Texas. It all started here, when 1980s legislation paved the way for local governments to hire private attorneys like Linebarger to collect unpaid taxes and hit debtors with big fees. This sparked such a boom in the industry that it even led a group of former partners to name a hunting ranch after that part of the state tax code -- dubbing it 3348 Ranch.

Sign from ranch that former Linebarger partners named after Texas tax code provision 33.48

Fast forward to today, and Linebarger is working for hundreds of local government agencies across Texas. It has won contracts to collect hundreds of millions of dollars a year from consumers for everything from unpaid parking tickets to overdue property taxes.

But getting all that business hasn’t come cheap.

“They’re just a big dog and have been that way for a long time,” said Craig McDonald, director of the nonprofit Texans for Public Justice (TPJ). “They have the ability through political connections and campaign contributions to squeeze a lot of competitors out of the market.”

Buying power

In a state known for limitless campaign donations, highly-paid lobbyists and political favors, Linebarger is one of the most politically-active businesses in Texas -- on both the state and local levels.

The firm doles out more on lobbying state lawmakers than some of Texas’s biggest corporate giants, including ExxonMobil, American Airlines and Halliburton, according to state records.

Linebarger doles out more on lobbying state lawmakers than ExxonMobil, American Airlines and Halliburton."

In a written statement, Linebarger told CNNMoney that it spent more than $1 million on lobbying in Texas over the past two years. Meanwhile, state records show that Halliburton, a much larger company, spent no more than $855,000 during the same period.

Linebarger and the partners that run the firm also have their hands in political campaigns across Texas.

Since 2000, the firm and its employees have spent more than $4.5 million on campaign donations, according to a TPJ analysis of state filings. And that doesn’t even count all of the local campaigns Linebarger donates to, which don’t end up in state campaign finance records.

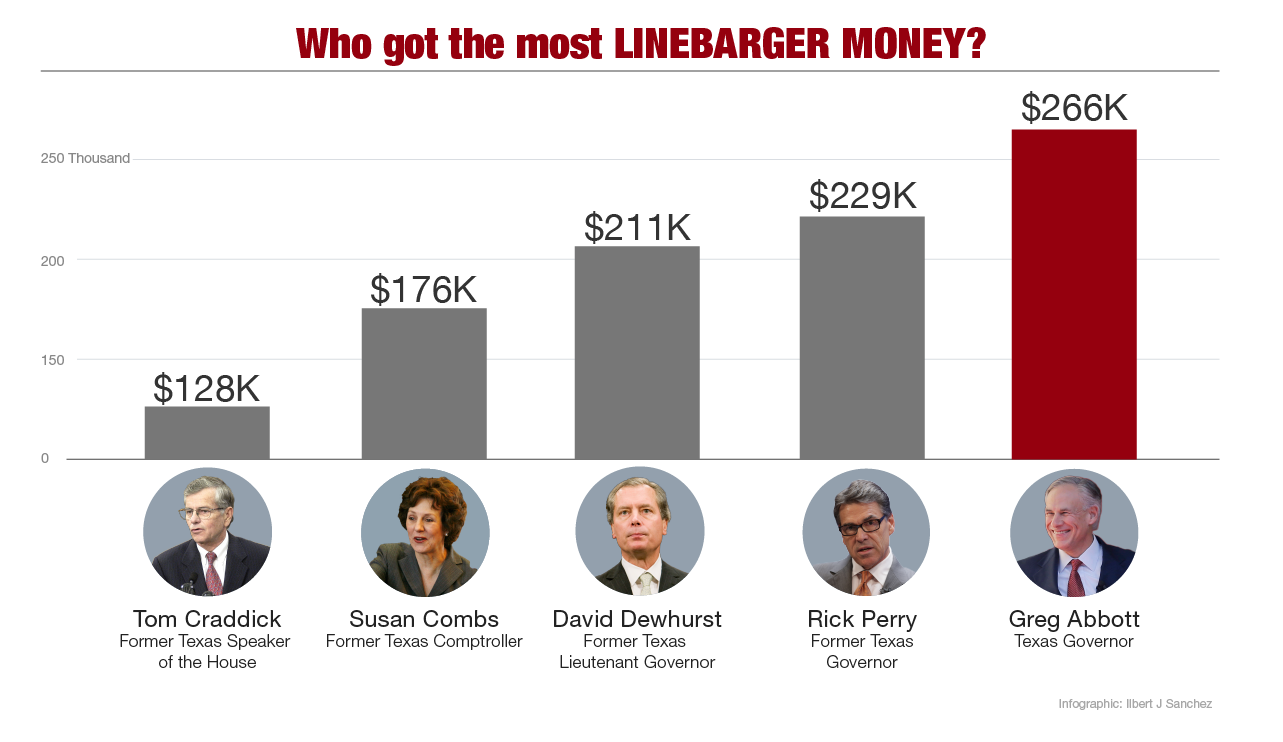

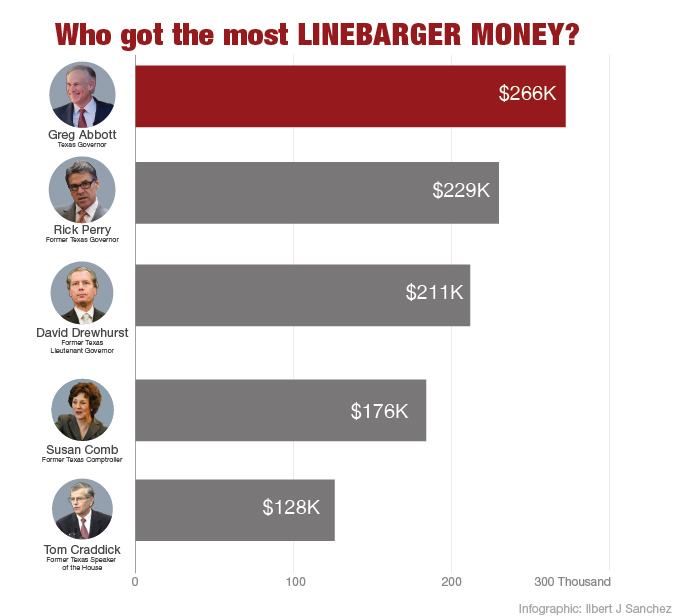

Source: Texans for Public Justice Since 2000, Linebarger has donated to hundreds of politicians across Texas, including the campaigns of these top recipients. Combs said political donations never played a role in her decision making. A spokesperson for Abbott said he had no say in which firms were hired by state agencies. The others did not respond to requests for comment.

Some of this money was doled out as Linebarger lobbied for favorable laws, including “spearheading the passage” of 2003 Texas legislation that allowed collectors to add a 30% fee to unpaid court fines for things like speeding tickets, according to a Linebarger firm presentation. This law, which then-Governor Rick Perry signed, helped spur the firm’s massive growth beyond its original business of collecting unpaid taxes.

Meanwhile, many of the local elected officials who have received donations from Linebarger are the same people who choose whether to hire the firm.

In Hidalgo County, Texas, for example, Linebarger has given more than $20,000 to the county commissioners’ campaigns since 2012. In November, those same commissioners unanimously voted to hire Linebarger to collect unpaid taxes, despite the fact that a Linebarger rival offered to charge delinquent taxpayers a lower fee.

Linebarger said it would like to think the county hired it because it was better qualified for the job. Hidalgo County officials said they hired Linebarger in part because it agreed to help the county save hundreds of thousands of dollars on the cost of the tax software, which Linebarger also provides.

Others think something else is at play. “It’s the money that gets them what they want,” McDonald said.

Shutterstock Texas State capitol, in Austin. For more about Linebarger's history in Texas and beyond, click on the image above.

But Linebarger says it’s just being a “good corporate citizen” and is following all applicable laws. It notes that it supports a number of charitable and educational causes as well, citing donations of $3.5 million over the past five years.

“We are actively involved in the communities in which we live and work,” Linebarger partner and chief marketing officer Michael Vallandingham said.

In fact, the firm says its whole business model is aimed at helping these communities fund vital services like school budgets and road repairs.

Political connections 'get the job done'

On the local government level, Linebarger also spends big money hiring influential consultants to lobby elected officials and help the firm land contracts.

Founding partner Dale Linebarger, who retired from the firm in 2006, said it’s these consultants who help the firm get its foot in the door with new clients.

You pay them basically to help you gain access to the officials."

- Dale Linebarger

Co-founder and former partner

“You pay them basically to help you gain access to the officials,” he said.

This practice is legal. But some of the people hired by the firm to do this kind of work have been accused of crossing the line.

Currently, two of the people Linebarger has hired to help it win and maintain business with government agencies are in the middle of separate bribery scandals in Houston and Dallas. In both cases, these consultants have been accused of funneling bribes to public officials who are in charge of deciding which companies get government business.

In Dallas, federal prosecutors allege that consultant Kathy Nealy took some of the income she earned from clients and passed along nearly $1 million in cash and other gifts, like the use of a BMW convertible, to a county commissioner. Both have entered not guilty pleas and are awaiting trial, and none of Nealy’s clients -- including Linebarger -- have been accused of wrongdoing. Linebarger said it is cooperating with the authorities and that it can’t comment further, while Nealy's attorney said "an indictment does not mean guilt."

A few hundred miles away in Houston, the FBI is looking into allegations that a local school board trustee received cash bribes from consultant Joyce Moss-Clay, who worked with Linebarger and other clients. A lawyer for the trustee acknowledged the investigation in a 2013 civil lawsuit filing, and a source close to the investigation said the inquiry is ongoing.

The source said that the FBI has been interested in whether Linebarger was involved in the alleged scheme, but the FBI wouldn’t confirm or deny the inquiry. Moss-Clay’s attorney also declined to comment.

Linebarger wouldn’t comment on this specific investigation either, but said that incidents involving rogue employees and contractors are rare and “should be kept in perspective.”

Another controversial but legal tactic: hiring lawmakers to do work for the firm at the same time they are serving on the Texas State Legislature.

In the past decade, the firm has paid millions of dollars to at least five current state lawmakers while they’ve been in office, according to state filings.

Linebarger wouldn’t comment on the specific lawmakers it hired and the kind of work they did, though it noted that legislators work part-time in Texas, which means that many have other jobs. The firm also noted that “relatively few” have worked for the firm over the years, and the majority have been licensed attorneys.

“They obviously understand government and how it works,” Vallandingham said.

Long-time House representative and licensed attorney Senfronia Thompson, for example, has received nearly $2 million from Linebarger since 2005, according to City of Houston financial reports requested by CNNMoney. Thompson did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

It may sound crazy but it's all perfectly legal -- at least in Texas.

While lawmakers like Thompson aren’t allowed to lobby state officials on behalf of Linebarger, they can use their political might at the local level.

But this practice can put unfair pressure on small town and city leaders to approve contracts in Linebarger’s favor, said Andrew Wheat, research director at Texans for Public Justice.

“That seems to strain the line of what’s right and ethical,” he said.

Putting lawmakers on payrolls. Flooding campaign coffers. Wooing officials. Influencing the law. All of these tactics combined take the firm’s power to a new level, said Jessica Levinson, a Loyola Law School professor and expert in political ethics.

“[It’s] an overly cozy relationship where money calls the tune,” she said.

Design by: Tiffany Baker/Web production: Tyler Sidell