Giant health insurers have been gobbling up smaller ones, partly to strike gold with a new government experiment allowing them to manage care for millions of the nation's sickest, poorest and oldest patients.

Some 15 states are in different stages of creating demonstration programs that allow managed care companies to care for so-called "dual-eligible" patients -- those enrolled in both Medicaid, which benefits poor Americans, and Medicare, a program for the elderly.

On Monday, Aetna (AET) announced it was buying Coventry Health Care (CVH), which already works closely with state Medicaid programs. The announcement came a month after WellPoint (WLP) said it will buy Amerigroup (AGP), another insurer that focuses on Medicaid. Last year, Cigna (CI) bought HealthSpring, which serves 122,000 dually eligible beneficiaries, its president Shawn Morris said in July.

What could be at stake, eventually, is the welfare of some 9 million poor, sick and older Americans, whose care costs federal and state governments more than $300 billion each year.

Whether the mergers will lead to better care or cost savings is a matter of debate. The eagerness of bigger health insurers to jump into serving dual-eligible patients is sending red flags to consumer advocates.

"From the consumers' point of view, this is a bad idea," said John Metz, chairman of JustHealth, a watchdog group in California. "With larger insurers taking more control, they tend to be even less accountable. With large insurers, we see that consumers are frequently having benefits, to which they're legitimately entitled to, being delayed or denied with no redress."

Health insurers disagree, saying that the bigger insurers are best equipped to provide the quantity and quality of services needed to launch these new programs, which are part of the health care law championed by President Obama.

"We believe we have the right capabilities to effectively manage these individuals to high quality outcomes and generate a reasonable return for our shareholders," said Mark Bertolini, Aetna CEO, about expanding into managed-care programs for "high-acuity" patients.

States have been flocking to get into these demonstration projects in hopes of improving care and lowering the costs for the priciest and sickest patients.

Right now, care and cost for dual-eligible patients is split. State-based Medicaid pays for long-term care, such as nursing homes, and federal Medicare pays for emergency hospital visits. The idea is that with one managed-care company overseeing all the care, there will be more coordination and cost savings, as companies seek the cheapest and most efficient way of keeping these individuals as well as possible.

So far, the federal government has doled out $1 million awards to 15 states, including New York and California, to coordinate care for dual-eligible beneficiaries through managed care starting in 2013. The program could expand into 26 states, ultimately affecting a population of 3 million, health care policy experts say.

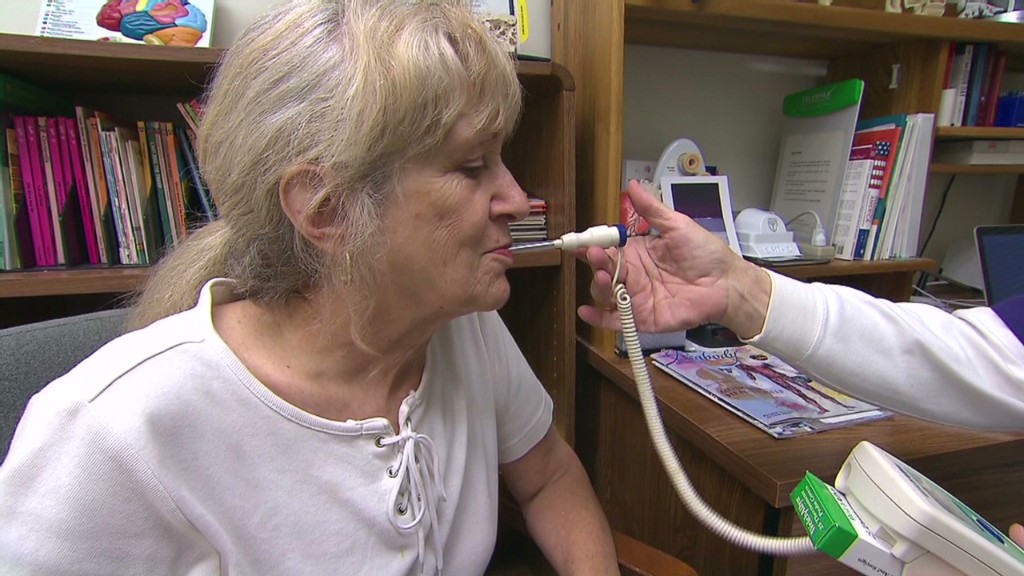

As a group, dual-eligible beneficiaries are more likely to suffer pricey diseases such as diabetes, lung disease, stroke, Alzheimer's disease and mental illness, said Melanie Bella, director of the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, in testimony before a Senate panel in July.

In Medicaid, the dual eligibles are 15% of enrollees but make up 39% of all Medicaid costs. In Medicare, they are 18% of enrollees and 31% of total costs.

Consumer advocates are worried about the demonstration programs, especially since big health insurers suggest that they expect to make money.

"There's a perception that this is going to be easy for the large insurers. That they're just going to have to cut costs," said Kevin Prindiville, deputy director at the National Senior Citizens Law Center. "But these people need a lot of services. They're sick and have chronic conditions. It's not a matter of just getting them to their primary care doctor. They have real needs."