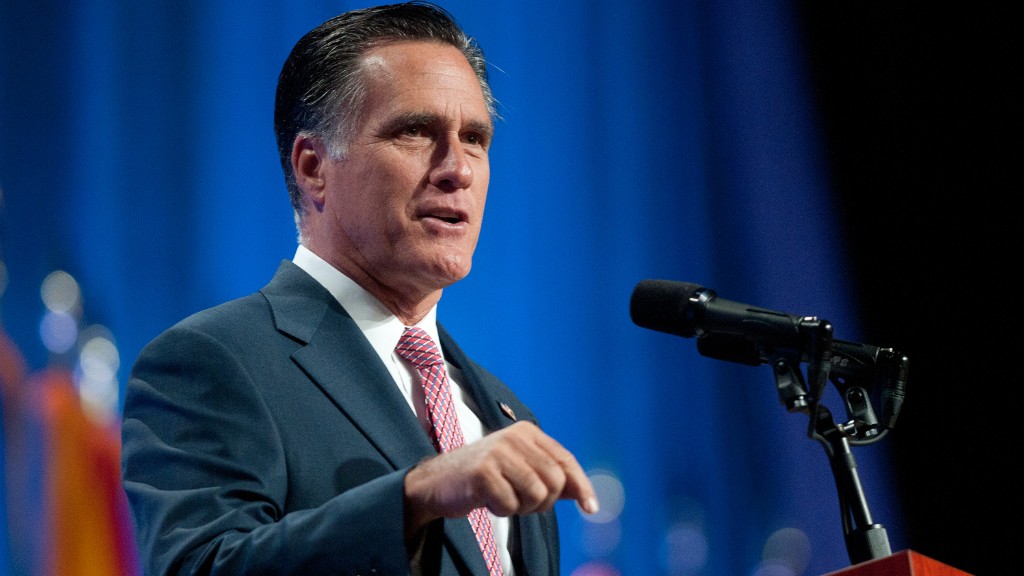

Mitt Romney says he would balance the federal budget by the end of his second term.

So what would it take? In short, a lot.

Unless the economy grows much faster than the Congressional Budget Office projects, Romney would likely need to cut funding nearly in half across many areas of government by 2020.

The Republican nominee's balanced budget promise trumps what even staunch independent fiscal hawks are calling for. Their first aim is to "stabilize the debt" -- meaning to stop deficits from growing faster than the economy.

To do so, they would cut deficits by at least $4 trillion over 10 years. And because doing so will be painful, they recommend distributing the burden through a combination of spending cuts and tax increases.

Romney, however, has ruled out raising taxes to help balance the budget. He does expect that his proposals would spur the economy, thereby generating extra revenue. But just how much more isn't clear.

He's also ruled out cutting defense spending -- indeed, his proposals may well increase it.

Medicare and Social Security spending, meanwhile, are not likely to be reduced during his time in office, since he has promised that his reforms to the programs would not affect those in or near retirement.

Related: Is Romney a tax cutter?

So where would he cut?

Recently, Romney said that on his first day in office he would cut non-security discretionary spending by 5%. Doing so he estimates would reduce spending by $500 billion a year by the end of his first term.

Specifically, Romney said he would:

--eliminate "programs that are not absolutely essential";

--cut subsidies for Amtrak, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Legal Services Corporation and the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities;

--limit funding growth for federal programs like Medicaid administered by states;

--cut federal employment by 10% through attrition and align pay with the private sector;

--combine agencies and departments;

--and reduce improper payments.

Rudolph Penner, a former director of the CBO, helped CNNMoney figure out what it would take for Romney to balance the budget by 2020.

The Romney campaign says his policies would generate 3% to 3.5% of inflation-adjusted annual growth between 2013 and 2022, which is above CBO's 2.2% projected average.

But since the campaign doesn't offer a year-by-year breakdown, and since growth is not guaranteed, Penner used CBO estimates as a baseline case.

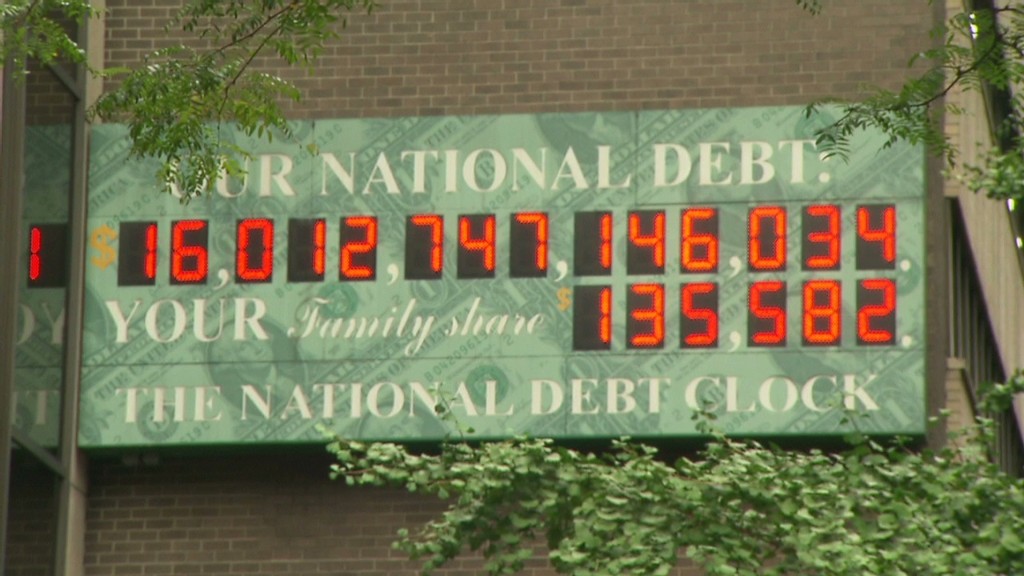

The CBO forecasts that the federal government will take in $4.2 trillion in revenue in 2020. That assumes current policies like the Bush-era tax rates remain in place -- something Romney favors. (Indeed, he wants to lower the rates further.)

Penner then estimates that spending on Social Security, Medicare, defense and interest on the debt would total $3.3 trillion that year. That leaves $900 billion of revenue left over to pay for everything else that the government funds.

Problem is, "everything else" in 2020 comes to $1.7 trillion.

Related: Mitt Romney talks to Fortune

So Romney would need to cut spending on most of the things government does by $800 billion, or 47%, that year. He's already promised to cut $500 billion, so he would need to cut another $300 billion on top of that.

Penner notes that such stark spending cuts might not be needed if the economy does better than the CBO forecasts, thereby generating more than $4.2 trillion in revenue.

Indeed, it's not unreasonable to assume the economy would grow somewhat faster if Romney lowers deficits and reforms the tax code, Penner noted. And "if the economy suddenly starts to recover faster for reasons that have nothing to do with his public policies, his numbers could work out."

But those are big "ifs." As is the likelihood that Romney will be able to garner enough support for his initial tough spending cuts.

"I would be skeptical that it is politically possible to cut $500 billion from the small programs that he considers," Penner said.