Some of the riskiest loans of the pre-financial crisis are back. But this time around, investors are being much more discriminating.

Enter collateralized loan obligations -- the one risky investment that survived the financial crisis virtually unscathed.

CLOs are created out of corporate loans that private equity firms, hedge funds and occasionally banks buy up, pool together, slice up and resell. Each slice carries its own risk rating and reward. In theory, holders of a AAA-rated slice would get paid even if a number of companies in the overall pool defaulted.

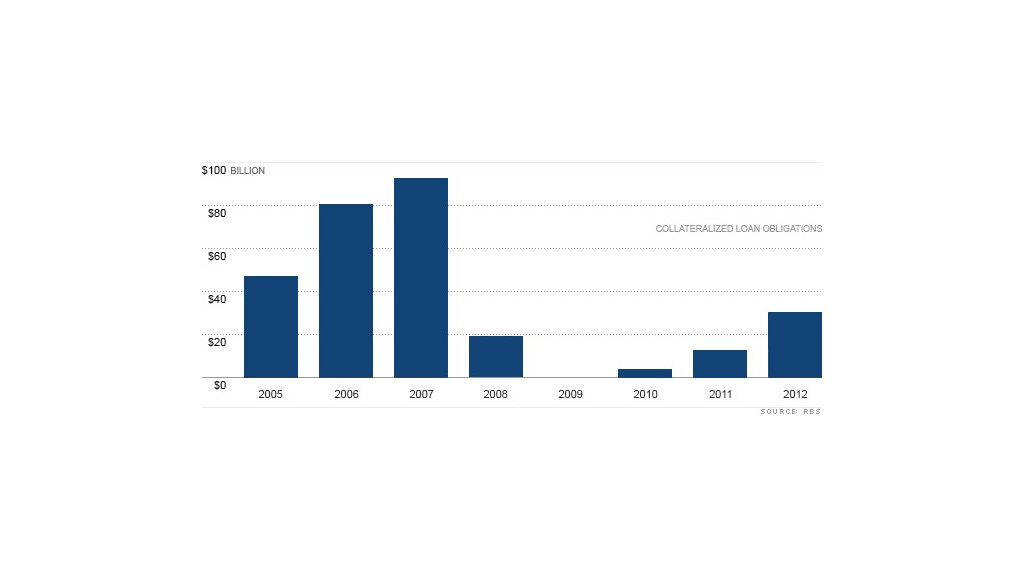

More than $30 billion of CLOs have been issued so far this year, according to researchers at RBS. That's more than double the $12.6 billion of CLOs issued in 2011. While 2012 levels will likely fall far below the height of CLO issuance -- $92.7 billion in 2007 -- it's a big comeback for a market that ground to a halt in 2009, when none were issued.

"Investors are getting back into this market because they recognize that these loans are different than the collateral backing other collateralized debt obligations, which observed high levels of defaults during the crisis," said Kenneth Kroszner, structured credit analyst at RBS.

Those included pools of subprime mortgages that nearly blew up the global financial system. During the subprime mortgage crisis, even AAA-rated CDOs stopped making payments because of the extraordinarily high rate of default. In contrast, fewer than 1% of the CLOs completely stopped paying returns, according to Moody's.

Investors are still steering clear of those subprime-related securities. "I don't think the CDO market will ever come back," said Matt Natcharian, who sells CLOs to pensions, mutual funds and other big investors as the head of structured credit investments at Babson Capital. "It's clear that the ratings of the collateral for those loans were not accurate and the diversification exposure proved to be elusive."

In the acronym-heavy parlance of the debt market, a CLO is also a type of CDO, but considered the least risky of the bunch. Aside from CLOs, there haven't been any new CDOs created since 2009, according to Dealogic data. That's a far cry from 2006 and 2007, when there were hundreds of billions of dollars worth of CDOs issued.

Today, newly-issued CLOs pay a better return for a AAA-rated security than almost anything else.

AAA-rated CLOs that mature in 5 to 7 years pay investors a yield of roughly 1.9%, according to JPMorgan Chase analysts. In contrast, pools of credit card loans rated AAA that mature in 5 years pay a yield of 0.6%. Pools of AAA-rated student loans with a 7-year maturity pay a yield of 1%.

The only securities that come close are pools of AAA-rated loans backed by commercial mortgages that yield roughly 1.8%, according to JPMorgan Chase.

Related: Bernanke weighing on bank profits

Pensions that are failing to meet annual targets are buying CLOs to generate cash flow to pay out to beneficiaries. So are major banks, since AAA-rated CLOs fulfill their need for highly rated capital demanded by new post-crisis regulations.

Still, CLOs are just a tiny fraction of the overall corporate debt markets. In 2012, corporations issued nearly $2 trillion of investment grade debt, and $281 billion of junk bonds. With increased demand, some issuers predict that yields will start falling, which could, in turn, curb some of the growth for CLOs.

Of course, on Wall Street, where there's a fee, there's a way. In a yield-starved world, some are hopeful that past mistakes won't be repeated.

"It's too early to tell whether certain types of deals will ever come back, but if they do, they would likely come back in a way that appropriately addresses the shortcomings of the previous generations of deals, some of which were structural, and some of which were due to the underlying collateral," said Joe Moroney, a senior portfolio manager at Apollo Group that runs its CLO practice.