Joseph J. Thorndike is a contributing editor at Tax Analysts and a columnist for Tax Notes magazine. His new book, "The Fair Share: Taxing the Rich in the Age of FDR," will be published later this year by the Urban Institute Press.

France's Socialist President François Hollande is the talk of Europe for his planned 75% tax rate on individual incomes over €1 million. When enacted, the new rate will catapult France to the top of the list of high-tax countries.

Hollande has defended the new rate as part of his effort to shrink France's budget deficit. But the new "supertax" is about more than raising money. It is also designed to make a point. "It's symbolic," Hollande has said. "It will show an example."

Indeed, that's the essential nature of very high rates on very rich people. They aren't really about raising money, although they can do that pretty well sometimes. Rather, they are designed to make a political statement about fairness and economic justice.

In Washington, of course, the fight is over whether to raise the top rate to a level just over half the amount they are arguing about in France -- to 39.6% from 35%.

By contrast, numerous countries have top rates in the low to mid-50s, including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Japan and Sweden. The world's highest rate is levied in sunny Aruba, where people making more than $171,000 face a top rate of 58.95%, according to figures compiled by KPMG.

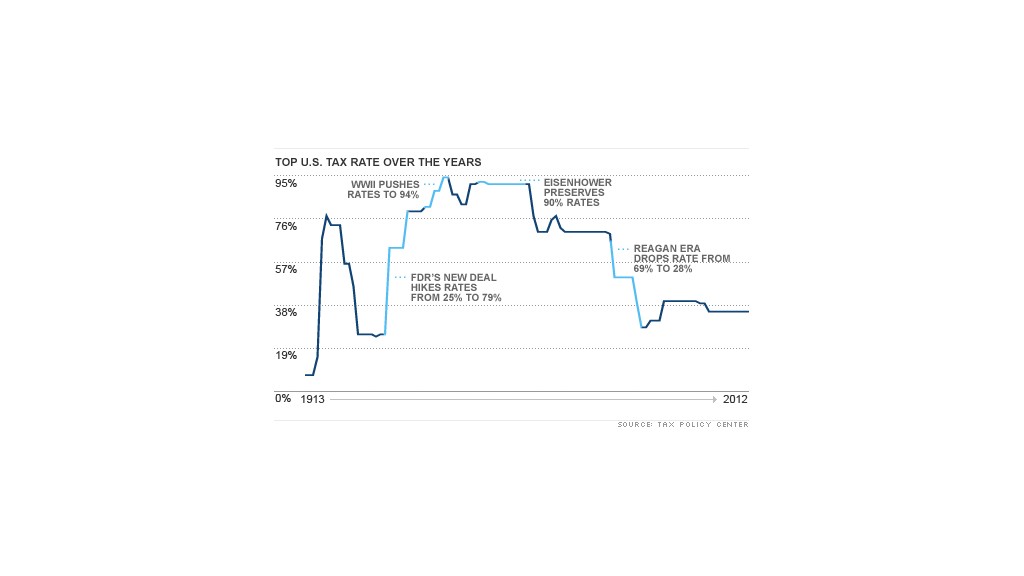

Still, that's a long way from Hollande's 75%. But U.S. history offers a refuge for Hollande and other fans of supertaxes on the rich. The United States had a top rate of 70% as recently as 1980. (Read more by this author: Nixon paid 6.1%)

Famously, President Reagan convinced Congress to slash that rate (and others) dramatically. High rates were a drag on the economy and a barrier to prosperity, he argued. By the end of Reagan's second term, the economy was booming and the top rate was just 28%. Coincidence?

Well, yes, at least according to fans of raising taxes on the rich. They point to the 1950s, when rates were as high as 90% and economic growth was solid. President Eisenhower was a genuine budget hawk, and he convinced his Republican Party colleagues to swallow hard and accept high rates as a fiscal necessity. (Related: 6 of richest in U.S. paid no tax)

So high tax rates are good for the country, at least in the face of deficits, right?

Not exactly. Most economists in the 1950s thought high rates were deeply pernicious. Sure, rich people would keep working in the face of high rates, but not quite as hard. Instead, they would focus their efforts on finding ways to avoid high tax rates.

Worse, high rates had a tendency to make the public more tolerant of tax avoidance and push lawmakers into enacting more loopholes.

Today, no one is arguing for a return to Eisenhower-era 90% rates. And reasonable people can disagree about where the bad effects of high rates really begin to show up. Is it at 40%? 50%? 75%? There's no easy or definitive answer, although some recent research from progressively minded economists would suggest that the number could be surprisingly close to Hollande's 75%.

Ultimately, however, such research is immaterial, at least in political terms. The argument for raising tax rates on rich people has never really been about revenue, incentives, or even growth. It's been about fairness, plain and simple. Fans of "soaking the rich" are happy to embrace studies that support their policy agenda. But it seems fair to say they would still like supertaxes even if they slowed growth.

Related: World's largest economies

Certainly that's been the lesson of U.S. history. Even the economists who crafted FDR's New Deal in the 1930s understood that big tax hikes on the rich came at a price. But, by and large, they also believed that such rates were necessary, politically if not fiscally.

Ultimately, those high rates came down. But it took a long, long time, and the damage caused by those rates played a key role in shaping the conservative revival of the 1970s. By the late 1960s, Republicans were ready to challenge that system, and the new GOP rode an antitax wave into power.

So if you're looking for the roots of modern antitax politics, you can start with the progressive tax rates of the 1930s. Soaking the rich can seem like a good idea, especially when times are tough. But it's a perilous agenda, at least for fans of progressive taxation.