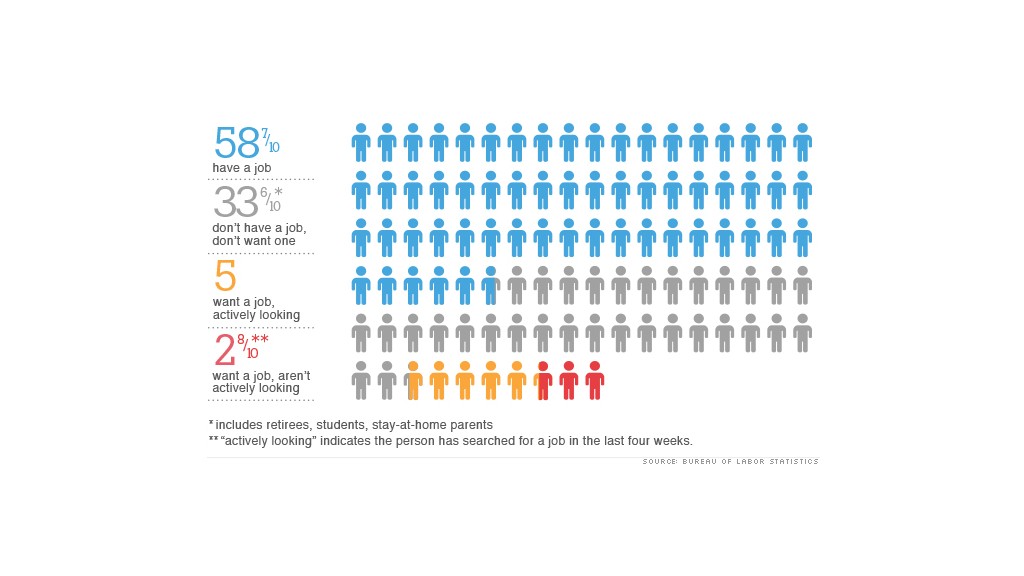

U.S. unemployment fell to 7.8% in September. But that doesn't mean the other 92.2% of adults are working.

The unemployment rate only measures people who have searched for jobs in the last four weeks, while millions of other out-of-work Americans aren't included.

But some economists think there's a better way to measure the health of the job market.

Along with the official unemployment rate, the Department of Labor also calculates something called the employment-population ratio, which measures the percent of the U.S. adult population that has a job.

The rate currently stands at 58.7%. While it jumps around slightly from month to month, it has essentially been stuck there for three years -- close to the lowest level since the 1980s.

That paints a much bleaker picture of the job market than the unemployment rate, which has fallen considerably in the last year.

"The employment-to-population ratio is the best measure of labor market conditions and it currently shows that there has been almost no improvement whatsoever over the past three years," Paul Ashworth, chief North American economist for Capital Economics said in a note to clients.

The ratio is also telling because it means that 41% of working-age Americans are out of a job for one reason or another.

So who are the non-working and why don't they have jobs?

Related: Why the unemployment rate won't keep dropping

About 5% of the adult population is "unemployed" in the technical sense of the word, meaning they don't have jobs but they looked for one in the last four weeks. Another 3% want a job but haven't search for one for at least a month.

That leaves about 82 million people who simply don't want a job. About 60% of them are either over age 65 or under age 25. Presumably, many are retirees or full-time students.

But the rest are in their prime working years, between ages 25 and 65.

Some could be stay-at-home parents, or people who can't work due to health problems. The wealthy day trader who lives off his investments is in this category too. So is the struggling artist or musician who might not want a traditional job.

Ultimately, the measure is really showing just how engaged the American population is in wage-earning jobs, arguably a better gauge of economy than the unemployment rate.

"The ratio expresses more clearly how many people find working to be a 'good or attractive deal,'" said Tyler Cowen, economist and director of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Related: Teaching jobs finally coming back

But while the indicator is clearly more intuitive than the unemployment rate, it's not a perfect measure of the job market either.

Demographic trends can play a role. For example, as women started entering the workforce in greater numbers in the 1960s, the ratio increased rapidly. Gradually, a larger portion of the adult population became officially employed.

On the other hand, the measure can make the job market seem worse if large groups are leaving the work force. For example, the ratio fell from about 63% in 2007 to 59% just two years later. Part of that drop is due to people losing jobs in the financial crisis. Another part is due to Baby Boomers retiring.

One way to avoid retirees clouding the data, is to look at the employment-population ratio for the 25 to 54 age group, says Greg Mankiw, Harvard economist and adviser to Mitt Romney. That number has also shown little improvement over the last three years, and is near its lowest level since the 1980s.

"One should not overstate the differences in the pictures that the various statistics paint," he said. "They all show that the current recovery is meager compared with most previous recoveries."

Another problem with the ratio is that it can be just as politicized as the unemployment rate. Many Republicans cried foul when the unemployment rate unexpectedly dropped two weeks ago. Likewise, the employment-population ratio is also subject to political rhetoric and has been used to blame the incumbent leadership for underlying economic weakness.

"The ratio makes the employment problem look worse, and in that sense is bad for Obama," Cowen said. "A deeper look, however, shows the ratio has been declining for many years, and that its ongoing decline predates Obama and most likely represents longer-run trends about the world of work.