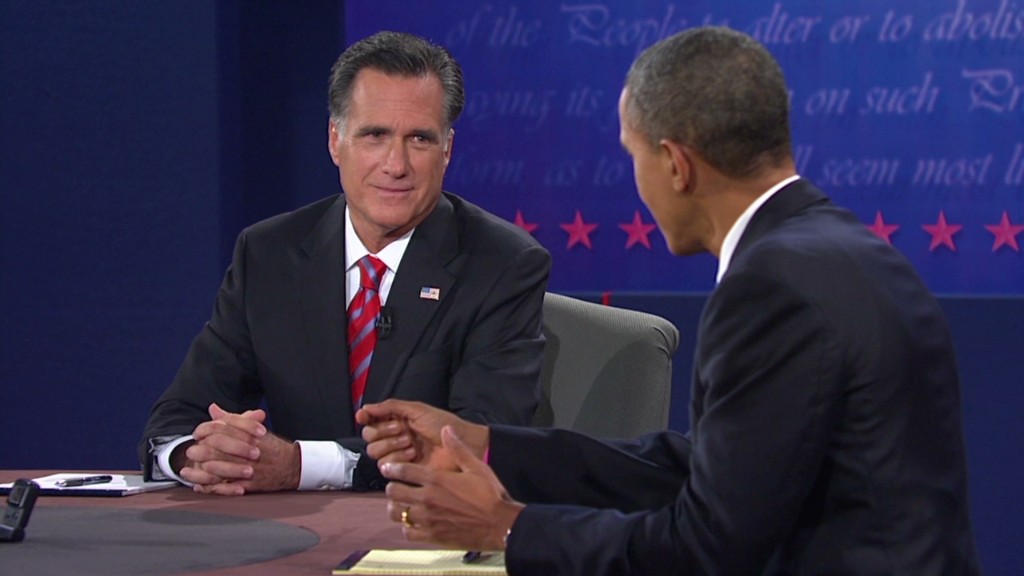

President Obama and Mitt Romney were sharply critical of China's trade practices in their final debate while underscoring the opportunity for the U.S. in a fair partnership with Beijing.

Both candidates said that China has great potential as a trading partner, but expressed worry over Beijing's actions. Obama touted the number of trade cases he has brought against China, while Romney pledged to designate the country a "currency manipulator" on his first day in office.

At the same time, both also offered conciliatory language, saying that the relationship between the world's two largest economic powers could flourish if China adheres to international standards.

"They have to understand we want to trade with them," Romney said. "We want a world that's stable. We like free enterprise, but you got to play by the rules."

The mixed messages were underscored by a puzzling exchange in which Obama described China as an "adversary," only to be contradicted by Romney, who until the final debate had been the more hawkish of the two candidates.

"China is both an adversary, but also a potential partner in the international community if it's following the rules," Obama said.

Romney responded: "We don't have to be an adversary in any way, shape or form. We can work with them, we can collaborate with them, if they're willing to be responsible."

The Obama campaign did not immediately respond when asked to explain the president's phrasing, but the comment does run counter to the general trend in Sino-U.S. relations, the tone of which has been largely positive over the past four years.

The remark also contradicts comments made by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton early in the Obama presidency.

"Some believe that China on the rise is, by definition, an adversary. To the contrary, we believe that the United States and China can benefit from and contribute to each other's successes," she said in 2009.

Whatever the intent, talking tough on China has become a campaign ritual for politicians of both parties -- even if, as experts predict, the rhetoric moderates after Nov. 6 regardless of who wins.

Related: China's currency becomes election issue

"Whoever wins on November 6 will have to prioritize the real challenges the U.S.-China commercial relationship faces," John Frisbie, president of the U.S.-China Business Council said in a statement.

"Rather than argue over who is going to be tougher on China, dealing with our fiscal challenges and strengthening our competitive profile is a better approach," he said.

Romney's vow to label China a currency manipulator is largely a symbolic gesture. The move could trigger talks with China, but no immediate, punitive actions are attached to the designation.

Economists are more worried about the second part of Romney's plan, which is to direct the Department of Commerce to institute countervailing duties if China "does not quickly move to float its currency".

Still, Beijing is not likely to find either tactic amusing. Xinhua, China's state-run news agency, published an editorial recently that warned of dire consequences should Romney follow through.

"If these mud-slinging tactics were to become U.S. government policies, a trade war would be very likely to break out between the world's top two economies," the agency said.

Related: Japan owns almost as much U.S. debt as China

Pressed during the debate about the risk of sparking a trade war, Romney said that China would not retaliate because they export a high volume of goods to the U.S., and have more to lose.

Wang Feng, director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center, said that Romney's argument was overly simplistic, and that Beijing would be making decisions based not on trade volumes, but China's domestic political concerns.