There's a big difference between raising tax rates and raising tax revenue. And the distinction may prove key in fiscal cliff negotiations between House Speaker John Boehner and President Obama over the next two months.

Boehner on Wednesday laid out in public his opening gambit for that deal-making.

House Republicans, Boehner said, are open to raising more tax revenue to reduce deficits -- a key Democratic requirement -- but only if it's done through tax reform that lowers income tax rates and in conjunction with entitlement reform.

Done right, Boehner said in public remarks in Washington, a reformed tax code can raise more revenue by curbing special interest loopholes and deductions and by generating economic growth.

That's very different than raising tax rates -- something that has been off the table for Republicans.

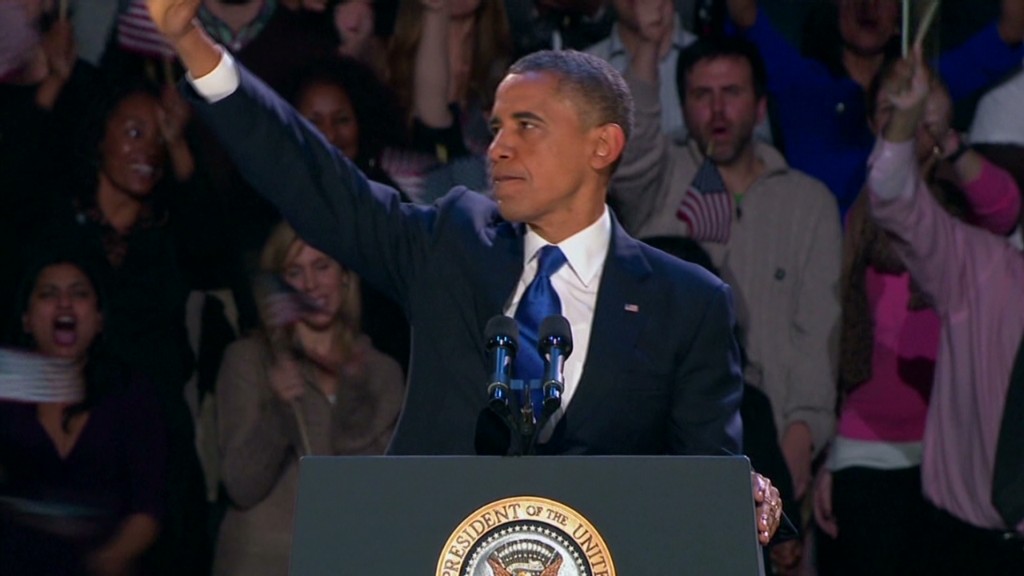

Obama, by contrast, has proposed making a down payment on debt reduction by letting the portion of the Bush tax cuts that apply to high-income households expire. That would mean the top two income tax rates would increase to 36% and 39.6% next year from 33% and 35% today.

(Related: Big business reacts to Obama re-election)

Boehner's remarks left several questions unanswered.

For one, how much of the new revenue would Republicans want raised through economic growth versus through curbing tax breaks?

Many tax experts believe smart tax reform can boost economic growth and thereby generate more revenue over time. But how much growth and when is unpredictable. And there's no guarantee that other factors that hurt economic growth won't undercut the revenue raised by tax reform.

In any case, the conventional way Congress assesses how much revenue a proposal would raise does not include potential economic growth effects of the kind Boehner expects, noted Jim Kessler, senior vice president for policy at the centrist think tank Third Way.

So an official "score" of revenue raised from such a tax reform plan would be most heavily reliant on the tax breaks that are curtailed.

And curbing tax breaks is not always an easy sell politically to either party, because it could mean many taxpayers end up paying more in taxes even when income tax rates are lowered, said Pete Davis, a former Capitol Hill staffer who now runs Davis Capital Investment Ideas.

Related: What Obama win means for fiscal cliff

In 1986, the last time the tax code was overhauled, lawmakers reduced rates and curbed tax rates for individuals. Most people got a net tax cut because lawmakers raised corporate tax rates a lot, Davis said.

This time, both Democrats and Republicans want to lower corporate tax rates, too. And if reform is to raise more revenue than the current system in great part by closing loopholes, more than half of taxpayers would likely see a net tax increase, according to Davis.

Given the country's long-term fiscal shortfalls, that may be necessary. But it will be a tough sell on Capitol Hill.

Nevertheless, Boehner's comments are a "promising start" to fiscal cliff negotiations, said Steve Bell, the economic policy director of the Bipartisan Policy Center.