Just four years after the worst shock to the economy since the Great Depression, U.S. corporate profits are stronger than ever.

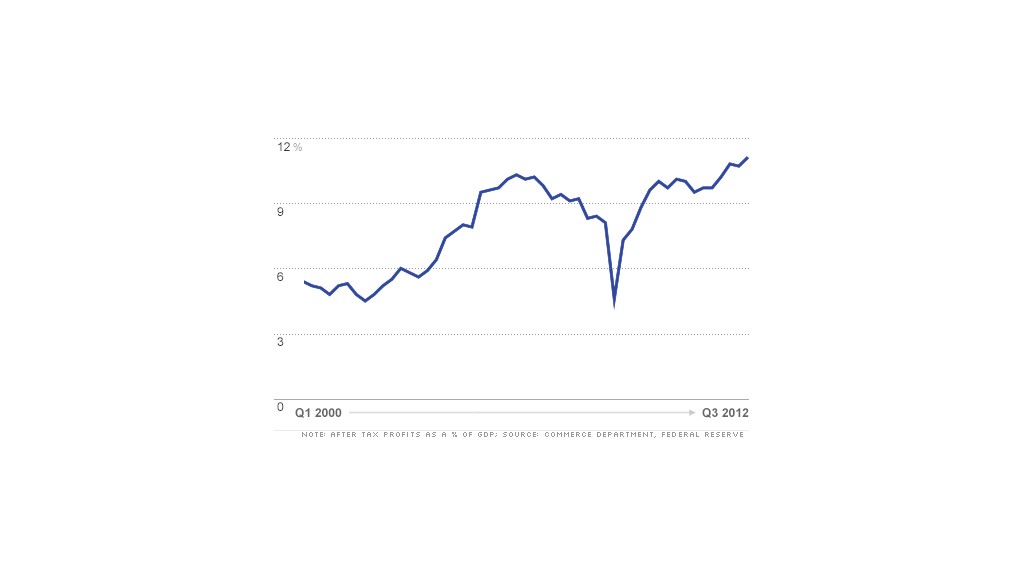

In the third quarter, corporate earnings were $1.75 trillion, up 18.6% from a year ago, according to last week'si gross domestic product report. That took after-tax profits to their greatest percentage of GDP in history.

But the record profits come at the same time that workers' wages have fallen to their lowest-ever share of GDP.

"That's how it works," said Robert Brusca, economist with FAO Research in New York, who said there is a natural tension between profits and the cost of labor. "If one gets bigger, the other gets smaller."

Profits accounted for 11.1% of the U.S. economy last quarter, compared with an average of 8% during the previous economic expansion. They fell as low as 4.6% of GDP during the recession.

"Corporate profits took a big hit in the recession like everything else, but they've seen a massive bounce back," said Heidi Shierholz, an economist with the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank. "Wages are determined by what's going on in the labor market and we haven't seen a big bounce back there."

Related: Why wages aren't rising

A separate government reading shows that total wages have now fallen to a record low of 43.5% of GDP. Until 1975, wages almost always accounted for at least half of GDP, and had been as high as 49% as recently as early 2001.

But overall economic growth has greatly outpaced growth in hourly wages and job creation since the end of Great Recession, so workers' share of the economic pie has dropped steadily. That's despite the fact that modest hiring by employers lifted total wages to a record $6.88 trillion in the third quarter.

"It's not because bad capitalists are keeping all the money," said Brusca. He said that businesses with high labor costs have either gone under or moved offshore.

Related: Most profitable companies

Shierholz said she doesn't think it's bad that business profits have risen. But the downward pressure on wages is hurting consumers' ability to spend, and thus the need for businesses to hire more people.

"[Businesses] have a capacity to employ more people, but it makes no sense to hire more people until you have demand for your stuff," she said.