Deportation. Detention. Barred entry. These are just some of the scenarios that people with HIV have to deal with when it comes to international travel.

Now, CEOs from 40 well-known companies are calling for countries to get rid of their HIV-related travel restrictions. Corporate leaders say the travel restrictions are discriminatory and detrimental to the globalized economy, in which companies have to be free to send employees around the world.

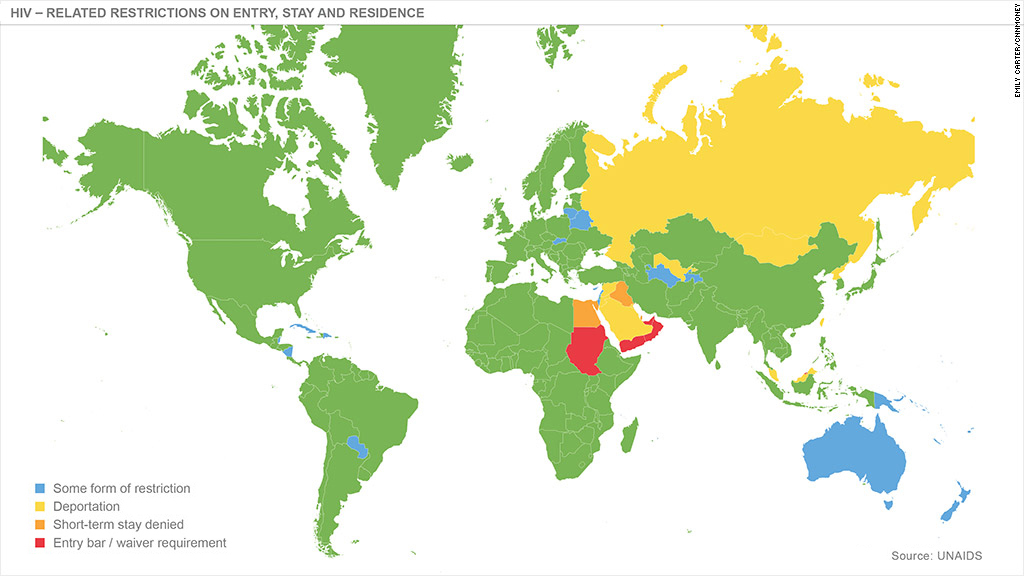

Currently, 45 countries have laws or policies in place that deport, detain or deny entry to people who are HIV positive, according to UNAIDS, the United Nation's program on HIV/AIDS. HIV is the virus that causes AIDS.

Five countries in the Middle East bar people living with HIV from entering. Another five, including Singapore, Egypt and the Turks and Caicos, require that people who want to stay in their countries for longer than five days have to show they do not have HIV.

Until recently, the U.S. too had regulations that barred HIV-infected foreign nationals from receiving a visa to enter the country. President Obama lifted them in January 2010.

The American restrictions were introduced in 1987, when Congress directed the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to add HIV to its list of diseases of public health significance. Foreign nationals were tested for the immunodeficiency virus during medical screening by U.S. immigration.

Related: The quiet scandal of the HIV home test kit

Business leaders who signed on to the pledge include CEOs of Coca-Cola (CCE),Aetna (AET),Viacom (VIA),Pfizer (PFE), the National Basketball Association,Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) and Gap (GPS).

Chip Bergh, CEO of demin-maker Levi Strauss, says the restrictions are bad for business. The San Francisco-based company's employees and community were greatly affected by HIV/AIDS and its repercussions during the 1980s, he said.

"Our employees are our competitive advantage, no matter what their HIV/AIDS status is," he said. "We're standing by our greatest asset, our talent, and we're making a move to end HIV/AIDS discrimination globally."

Many of the laws and policies were enacted in the 1980s, when HIV first came into the public consciousness, according to Bertil Lindblad, direct of UNAIDS in New York. He said that the policies resulted from a combination beliefs that HIV could be caught through the air, that it could not be treated, and that there was no reliable test to detect it. All three of those factors have since changed.

"There was a fear about HIV and stigma and discrimination," Lindblad said. "HIV in some countries is thought of as a social evil. In some places it is part of bigger human rights issues, where homosexuality is illegal."