Often missing from the hyper-politicized debate over spending cuts and tax increases is a central point: Why the federal budget is on an unsustainable course.

Today, the United States spends about 71 cents of every federal tax dollar it collects on the Big 4: Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security and interest on the debt.

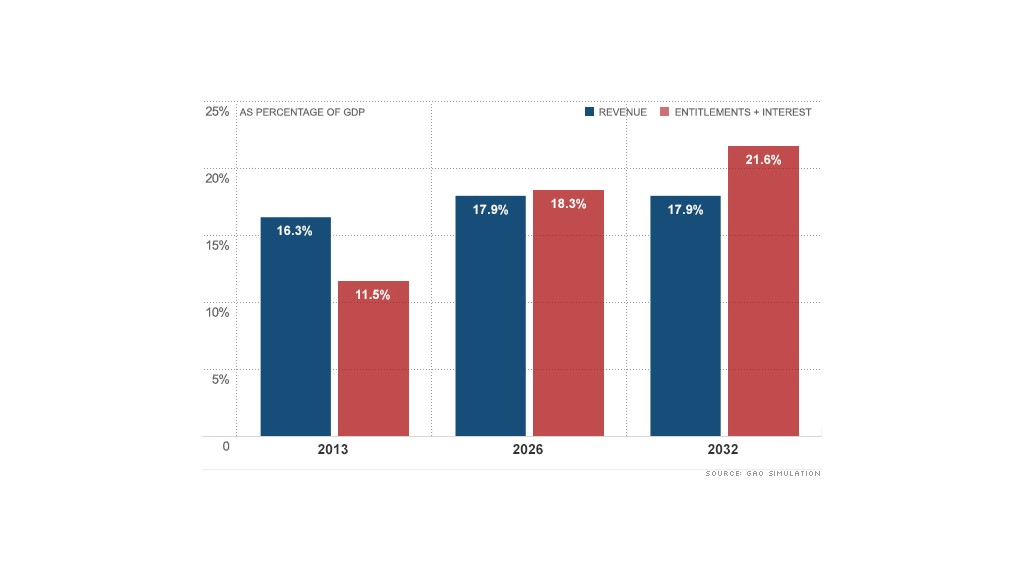

By 2026 -- just 14 years from now -- if Congress acts as it has in the past on the budget, the Big 4 could suck up all federal tax revenue, according to the latest long-term fiscal outlook from the Government Accountability Office.

In other words, by 2026 there could be nothing left to pay for anything else. Like defense. Or education. Or medical research, food safety, air traffic control, highways, national parks, veterans' benefits. You name it.

The picture gets worse after that. By 2032 -- just 20 years from now -- the Big 4 under this scenario would cost 121% of all federal revenue projected to come in.

And by 2040, more than half of all revenue would be eaten up by interest payments alone, according to GAO simulations.

So what's the best way to address this predicament?

The knee-jerk solution from the right is to slash entitlement spending and shrink government, despite the fact that growth in the elderly population is a big reason for rising entitlement costs, particularly Medicare.

The knee-jerk response from the left is to tax the rich, despite the fact that you can't pay for everything on the back of a small number of people.

The Congressional Budget Office distills the problem: "[To] have a substantial budgetary impact would require large numbers of people to pay more in taxes or receive less in government benefits or services."

That's why many budget experts recommend a combination of tax increases and spending cuts so no one group of people is disproportionately burdened.

The first step is to stop deficits from growing faster than the economy, and to stabilize the amount of total debt as a share of GDP. To do that, policymakers would need to reduce deficits over the next decade by at least $3 trillion. To actually put the debt on a downward trajectory would require much more than that.

So why not let the fiscal cliff take effect?

The fiscal cliff -- the result of Washington's habit of enacting "temporary" fiscal policies -- would actually curb deficits by $7 trillion, starting in earnest next year.

But how deficits are reduced matters.

Even independent deficit hawks aren't demanding that deficits be slashed immediately.

In fact, they've warned all along about the dangers posed by the cliff.

"The sudden and blunt nature of ... the fiscal cliff would have a devastating impact on the economy," the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget noted in a recent blog post.

Some call for extra stimulus to be injected into the economy next year.

Among them are economist Alice Rivlin, a Democrat, and former Senate Budget Chairman Pete Domenici, a Republican, who co-chaired a debt reduction task force for the Bipartisan Policy Center.

They've proposed a framework that would let lawmakers avert the fiscal cliff and come up with a long-term debt reduction plan to be voted on next year.

Their framework would make a small down payment on deficit reduction phased in over 10 years but would also create a one-time income tax rebate in 2013 worth $120 billion to help support the economic recovery.

Why worry about debt when there are more immediate problems?

True, Treasury bond rates remain extremely low -- a signal that investors think the United States is a good bet in tough times. So in that sense, U.S. debt is not a problem right now.

But the reason budget experts are pushing lawmakers to decide on a long-term debt-reduction plan that takes effect gradually is this: The longer the country waits, the more onerous and sudden the changes will have to be, making it harder for Americans to adjust their plans.

"The longer action is delayed, the greater the risk that the eventual changes will be disruptive and destabilizing," the GAO notes.

And, the CBO adds, waiting too long would require sacrifices from those in or near retirement -- a group that both parties say they want to protect.