Just a few weeks ago, Congress narrowly avoided pushing the country off the fiscal cliff. Now it faces a potentially bigger risk to the economy: the need to raise the debt ceiling.

To help separate fact from fiction in the battle, here's what you need to know about the issue.

What is the debt ceiling exactly? It's a cap set by Congress on the amount of money the federal government may borrow. The limit applies to debt owed to the public (i.e. anyone who buys U.S. bonds) plus debt that the Treasury owes to government trust funds such as those for Social Security and Medicare.

Why does it need to be raised? The debt ceiling needs to be raised periodically because both parties in Congress have approved tax cuts and spending increases over the years, knowing full well they will add to deficits. By doing so, they increase the country's future borrowing needs.

That's why raising the debt ceiling is not a "license to spend more," as some Republicans assert. It simply lets the Treasury Department continue to pay all the country's obligations that Congress has already approved -- whether it's a payment to a federal contractor, a Social Security check to a senior, or interest on the debt to a bond investor.

Since March 1962, Congress has raised the debt limit 76 times, according to the Congressional Research Service. Eleven of those times occurred in the past decade.

How high is the debt ceiling now? The ceiling is currently set at $16.394 trillion. The country's borrowing hit that mark on Dec. 31.

As a result, Treasury can't borrow any new money in the markets (although it still is allowed to rollover existing debt). So it has begun to use "extraordinary measures" to temporarily stave off the risk that the country will default on any of its obligations.

What are "extraordinary measures" and how much time can they buy? Treasury has four options, which combined can raise $200 billion.

The biggest of them is to temporarily stop reinvesting federal workers' retirement savings in special-issue short-term bonds.

Treasury has said that normally $200 billion can cover federal borrowing needs for about two months. But how much it buys this time around remains uncertain.

Treasury said on Jan. 14 that it expects to exhaust its extraordinary measures sometime between mid-February and early March. Earlier, the Bipartisan Policy Center had estimated the deadline would come as soon as Feb. 15 but no later than March 1.

What happens if Congress doesn't raise the debt ceiling in time? It's impossible to say with certainty. But generally speaking, nothing good will come of it.

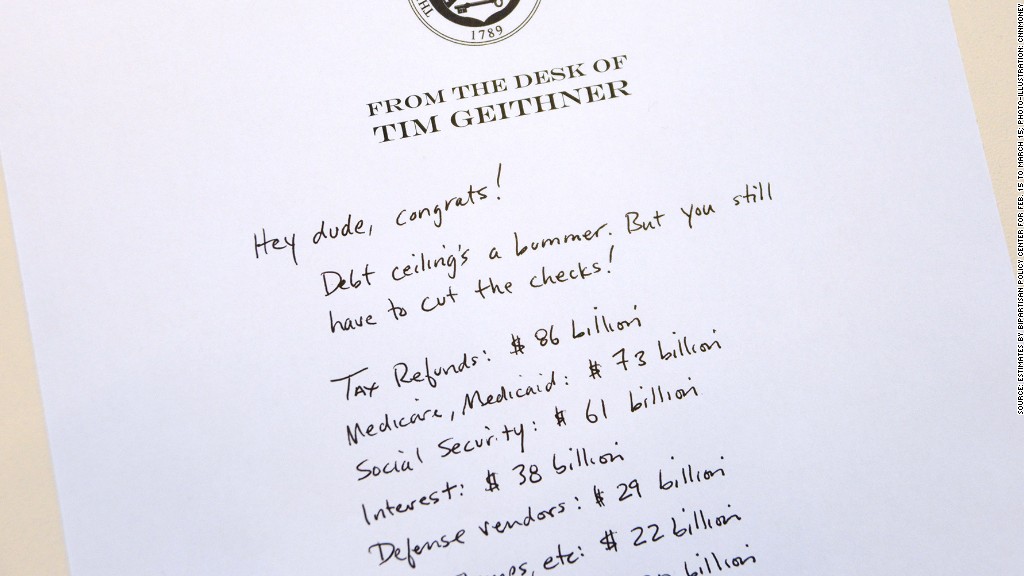

Treasury would not be permitted to borrow. So it would only be able to pay those bills for which it has enough revenue on hand. Problem is, there won't be enough revenue on hand to cover the payments due on any given day.

So who would get paid and who would get stiffed? Treasury would be forced to make legally questionable decisions -- either picking winners and losers, or choosing to delay payments to everyone.

"The reality would be chaotic," the Bipartisan Policy Center concludes in an analysis of Treasury's cash flow.

Some say the country could avoid default if Treasury simply chooses to pay interest due to bondholders first. It's not as simple as it sounds, but that is what most experts expect Treasury would do since defaulting on U.S. bonds would cripple the economy, send markets into a tailspin and potentially "trigger another catastrophic financial crisis," in the words of the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee.

But if the debt ceiling standoff persists, there's no guarantee that paying interest but shirking other legal obligations will protect the country from the perception of default or at least instability.

If the debt ceiling isn't raised in time, will there be a government shutdown? Not technically, but effectively it may feel like a partial one.

A real government shutdown occurs if lawmakers fail to appropriate funds for federal agencies and programs. Without appropriated funding, government operations would cease, except for essential services.

By contrast, if the debt ceiling isn't raised in time, the government remains open and Uncle Sam has revenue coming in to pay for government services and agencies. Just not enough revenue to pay for everything.

"There would have to be severe cutbacks, but it is unlikely that large parts of the government would be shut down completely," said former Congressional Budget Office Director Rudolph Penner.

But the longer the debt ceiling crisis lasted, the harder it would be to keep government operations running. "After two weeks you'd have absolute paralysis in the federal government," said Steve Bell, economic policy director at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

What's all the noise about the 14th Amendment? If Congress fails to raise the debt ceiling, some believe the president could choose a "nuclear option" and invoke the 14th Amendment.

That amendment states: "The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law ... shall not be questioned."

By invoking the 14th Amendment, the argument goes, Obama could direct the Treasury secretary to keep borrowing in order to pay the country's obligations.

The White House has rejected the suggestion several times. But minds may change, experts say, if the country is really on the brink of default.

It would, however, be risky politically.

And the country could still be hurt financially. Invoking the 14th Amendment could spark a constitutional showdown -- not exactly an affirming message to send markets already questioning Washington's ability to govern.

What about a $1 trillion platinum coin? Another instant-presto fix that some experts believe could be used to avert default is the creation of a $1 trillion platinum coin. Then again other experts think the idea is legally questionable and in any case not a bright move.

The idea goes like this: Treasury is not allowed to print money. But because of a legal loophole it is allowed to mint platinum coins. If it opts to mint a $1 trillion coin, it could deposit it at the Federal Reserve and thereby keep paying the country's bills even though the debt ceiling hasn't been raised yet.

"Minting a $1 trillion coin sounds like the plot of a Simpsons episode or an Austin Powers sequel. It lacks dignity," writes Donald Marron, a former Congressional Budget Office director, in an opinion piece.

Treasury beat back expectations and rejected the idea in a statement on Jan. 12. "Neither the Treasury Department nor the Federal Reserve believes that the law can or should be used to facilitate the production of platinum coins for the purpose of avoiding an increase in the debt limit," Treasury said.