Chances are slim that Congress will avert the automatic spending cuts before they take effect on Friday. It's more likely lawmakers will reach a deal to replace the cuts after they begin.

But there's no telling when.

Funding for numerous federal agencies and programs will be slashed, half from defense and half from nondefense spending.

Generally speaking, both parties say they don't want the cuts to kick in as planned.

Just how the cuts would be replaced -- if they are -- remains unclear, however.

Scenario 1 - Shutdown threat pushes Congress to act: The current measure funding the government expires on March 27. Known as a continuing resolution, that law is separate from the one that mandates the automatic cuts. It sets spending levels and authorizes the government to continue operating.

If lawmakers don't agree to new funding levels soon, the government will shut down on March 28 and remain closed until Congress reaches a deal.

A shutdown wouldn't bode well for either party. Most government offices and services would be shuttered. The only exception: services deemed "essential" -- those related to the safety of human life and protection of property. Taxpayer money would be wasted in the process because it costs money to close the government and to ramp it back up when Congress reaches a deal.

The urgency to avert a shutdown might spur lawmakers to agree on a replacement of the automatic spending cuts as part of a final deal.

Related: What you need to know about the cuts

Scenario 2 - Lawmakers keep fighting over the cuts: The pressure to avoid a shutdown may be so great that Congress takes the threat off the table before it even addresses the spending cuts.

One possibility is that House Republicans quickly pass a continuing resolution for six months until Sept. 30 at current funding levels, which would fall once the so-called sequester kicks in.

Senate Democrats, not wanting to be seen as the ones risking a government shutdown, sign on and decide to fight for a replacement to the automatic cuts later.

In that case, interest groups would step up pressure on lawmakers once the pain of the cuts really starts to set in.

"The sequester is a slow bleed that gets worse as it goes on," said Sean West, the U.S. policy director for the Eurasia Group.

Indeed, its bite won't be nearly as deep in March as it will be in April and beyond.

For instance, while more than 2 million federal workers may face unpaid furloughs for a day or two a week, those furloughs likely wouldn't start before April.

And the White House budget office may be able to instruct some agencies to hold off on implementing cuts for a short period of time.

The elephant in the room - Spending vs. taxes: Of course, there's no guarantee that lawmakers can bridge their ideological differences over spending and taxes.

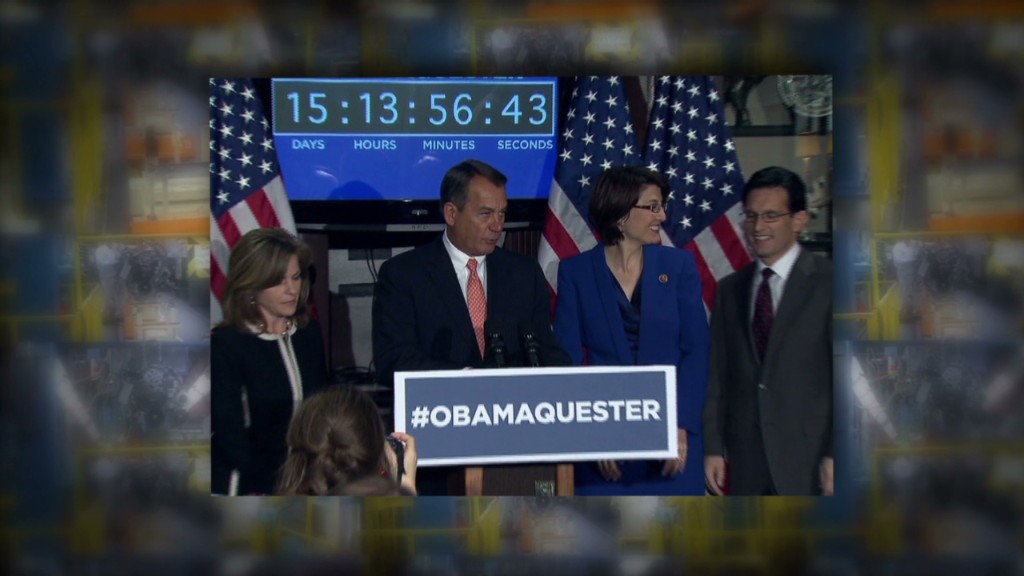

Democrats have proposed replacing the automatic spending cuts with a combination of tax increases and spending cuts. Republicans want to replace the defense cuts with more non-defense cuts, and they oppose any revenue increases.

West of the Eurasia Group believes the two sides will agree on a replacement package by April. It may include mandatory spending cuts and tax increases, but the kind both parties can tolerate.

For instance, revenue increases might come from raising fees rather than tax rates, and thus be more palatable to Republicans. And mandatory spending cuts may not affect Medicare or Social Security benefits but rather reduce non-health-related spending -- for instance, by reforming federal retirement programs, he said.

Whatever ends up happening, get ready for a long and messy few weeks. Or months.