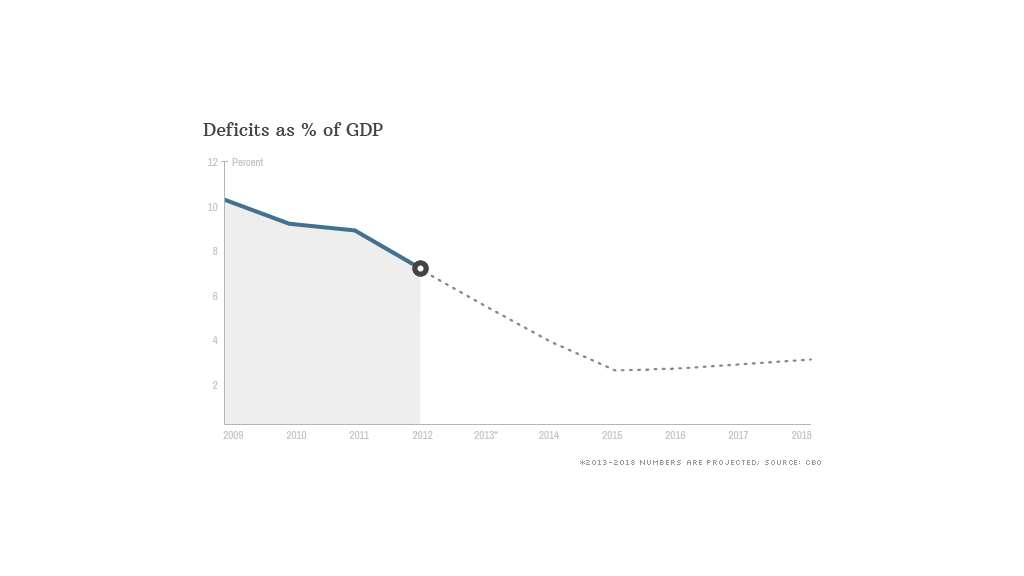

Deficits are falling. A lot.

Remember 2009, the depths of the economic crisis? That year, the country spent way more than it brought in and ran an eye-popping shortfall that topped 10% of the size of the economy.

This year the deficit is expected to be half that -- around 5.3% of GDP, the Congressional Budget Office estimates.

And by 2015, it's projected to drop to 2.4%.

What's more, the national debt that has accumulated from annual deficits is also projected to fall to an estimated 73.1% of GDP in 2018 from an estimated 76.3% today.

Related: Does debt slow growth?

There are several reasons for the downward trend. The economy is on the mend. Incoming federal revenue has risen from 60-year lows and will soon top its historical average for much of the next decade. Spending, meanwhile, has come down from 60-year highs.

And, of course, projections have improved because Congress and President Obama have signed off on $4 trillion of deficit reduction that is set to unfold over the next decade. That assumes the roughly $1 trillion in forced budget cuts that went into effect last month are kept on the books or replaced with something comparable, as Obama has proposed.

So does this mean everyone can shut up now about needing to reduce deficits?

"The deficit is manageable in the medium-term given growth coming back on-line, low borrowing costs, and political decisions to cut spending in the 2011 debt deal and raise taxes in the 2012 tax deal," said Sean West, U.S. policy director at the Eurasia Group.

But the deficit reduction put in place so far won't do much to address the country's long-term fiscal situation, which is where the real debt problem lies.

"It would be naïve to think we're out of the woods. At the end of the decade we're back in the soup on entitlements. And debt servicing costs start to become a problem as well," said Greg Valliere, chief political strategist at Potomac Research.

Here's what he means: Because Congress has yet to get a handle on the large, long-term imbalances between spending and revenue, deficits are expected to start rising again by 2016 and debt will resume its upward trek by 2019.

Those imbalances will be driven by growth in spending on entitlement programs, especially Medicare, due to two factors.

The first is the aging of the population. The share of the population over 65 is expected to grow to 19% by 2029, up from 13% today, according to the Government Accountability Office. The second is the growth in health care costs, which regularly tops inflation.

Meanwhile, current tax policy won't generate the revenue needed to adequately support the expansion in spending.

As for interest on the debt, assuming current policies stay in place and interest rates start to rise as the economy improves, the CBO projects that by 2023 interest costs alone will be $857 billion, or nearly four times what the federal government is paying today. As a percent of GDP, interest costs would more than double to 3.3%, up from 1.4% this year.

That's why independent budget experts have been saying that policymakers will need to cut long-term spending, raise taxes or do both to head off a future budget crisis.

The GAO now estimates that under current policies and fiscally restrained assumptions going forward federal revenue by 2030 won't be able to cover much more than spending on interest and the big entitlement programs (Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security and health insurance subsidies).

By 2040, it won't even adequately cover those.

Barring serious reforms, the numbers would worsen thereafter.