Should a life-saving drug that can be profitably sold for far less cost more than $100,000 per year?

A group of more than 120 cancer researchers and physicians took the unusual step this week of publishing a research paper taking aim at pharmaceutical prices they see as exorbitant and unjustifiable.

Drug companies are profiteering, the doctors say, by charging whatever the market will bear for medications that patients literally can't live without.

The paper, published online in the American Society of Hematology's medical journal Blood, analyzes and criticizes the cost of drugs used to treat chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), a rare type of cancer that responds very well to drug therapy. The 10-year survival rate for CML patients now tops 80% for those who receive targeted drugs -- but the annual price tag for the treatment is usually in the six-figure range.

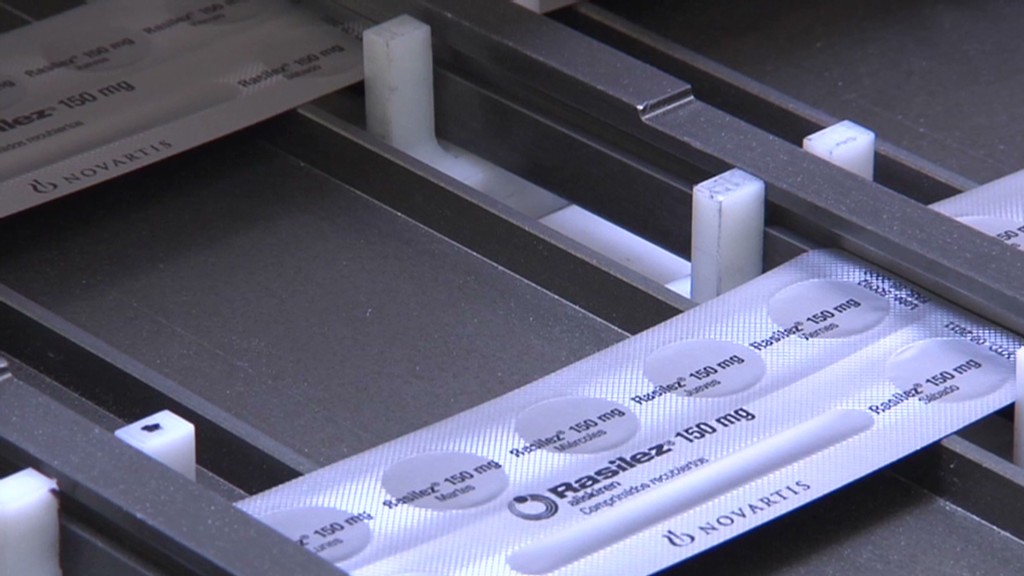

Those prices bear little relation to what the drugs actually cost to develop and produce, the doctors say. As an example, they zero in on the case of imatinib, a drug sold by Novartis (NVS) as Gleevec (in the U.S.) or Glivec (in most international markets).

Gleevec is the kind of miracle pill cancer researchers dream about. Introduced in 2001, the drug and others in its class dramatically increased the survival rate for CML and transformed it from a lethal disease to one that is usually chronic but manageable. It's like having hypertension or diabetes, doctors say -- so long as you take your daily drugs.

Novartis first sold Gleevec in 2001 for an annual cost of $30,000, a price the company acknowledged was steep.

"We agree with those who say the price we have set for Gleevec is high. But given all the factors, we believe it is a fair price," Daniel Vasella, Novartis' CEO at the time, wrote in Magic Cancer Bullet, a 2003 book he penned about his company's wonder drug.

That "fair price" nearly tripled over the past decade. An annual course of Gleevec now wholesales for more than $76,000 in the U.S., according to Novartis. The retail price that patients or their insurers pay is typically much higher.

The Blood authors say lowering those prices will help save the lives of patients who cannot afford to pay. "We believe the unsustainable drug prices in CML and cancer may be causing harm to patients," they wrote.

Related story: Why one doctor 'gave up on health care in America'

Gleevec is Novartis' bestselling drug, generating revenue of $4.7 billion last year. The company says the drug's current price tag is justified by its success.

"Thousands of people are alive today because of the development and introduction of targeted CML therapies," company spokeswoman Julie Masow said in a written statement. "Today, nine out of ten patients with CML have a normal lifespan and are leading productive lives."

That answer doesn't please Dr. Hagop Kantarjian, the paper's lead author and chairman of the leukemia department at the University of Texas' MD Anderson Cancer Center.

"These price increases do not reflect the cost of development of drugs or the benefit they provide to the patient," he told CNNMoney. "They are simply related to the drug companies' wish to increase profits beyond a reasonable range."

Drug companies like Novartis and its rivals emphasize that it's usually insurance companies, not individual patients, bearing the costs for pricey drugs. Most U.S. patients pay less than $100 a month out of pocket for Gleevec, according to Novartis, and those who don't have coverage often qualify for free "patient assistance" giveaways. Globally, one-third of the Gleevec that Novartis produces is given away for free, the company said.

But Kantarjian said he and his collaborators want to draw attention to a larger point: Drug prices for all sorts of conditions are far out of line with any economic basis. That's an unsustainable trend, in his view.

Kantarjian hopes other doctors will take up the cause and start analyzing -- and speaking out against -- the rapidly rising costs of drugs in their fields.

"CML happens to be my area," he said. "We wanted to provide a model that other tumor experts and specialists in other fields -- say cystic fibrosis or multiple sclerosis -- can follow."

He's also hoping the pharmaceutical companies will take action. The inspiration for his group's paper came, Kantarjian said, from a protest movement started late last year by a group of physicians at New York's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. The doctors announced in a New York Times op-ed that they would no longer prescribe Zaltrap, a "phenomenally expensive" cancer drug they said was no more effective than its cheaper rivals.

One month after that op-ed ran, Zaltrap's maker, Sanofi, cut the drug's price tag in half.

Kantarjian would love to see similar action in his field. But his main goal, he said, is to bring the pricing issue out of the shadows.

"I'm hoping that this will be the trigger for a national dialogue on cancer drug prices, and the prices of drugs in general," he said. "Patients are suffering. And some patients are dying."