Cray, the company often credited with building the world's first supercomputer, is shrinking its largest machine down into a more affordable package.

This isn't the kind of computer a young hacker would buy to toy around with in a garage: It'll set you back $500,000. But compare that to the $1 billion-plus price tag on, say, Fujitsu's "K" supercomputer, installed in Japan in 2011, and you've got a screaming deal.

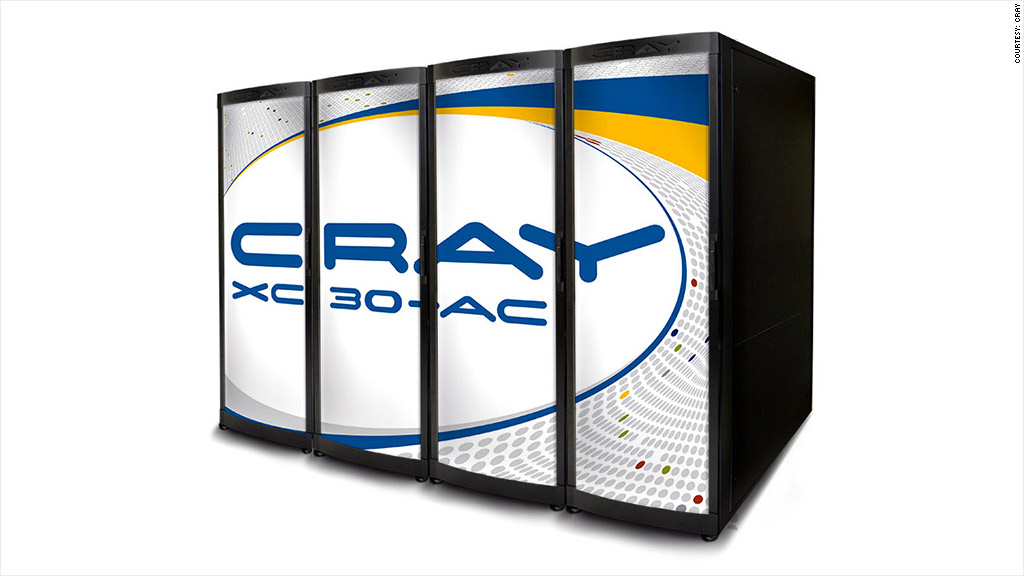

Cray's XC30-AC, which goes on sale Tuesday, is Cray's cheapest supercomputer. It has the same software and processors as its big brother, the XC-30, which typically sells for $10 million to $30 million, depending on the configuration. If you were to run a problem on the smaller machine while running the same problem on an equal number of processors in the high-end Cray, you'd get your answer in the same amount of time.

That sets it apart from past Cray attempts to target a lower end of the market, and from rival offerings at IBM (IBMSY), HP (HPQ), Dell (DELL) and other competitors. Those vendors also sell "discount" supercomputers, but they tend to use different components than their top-of-the-line machines, said Steve Conway, an analyst at IDC.

The very concept of a "supercomputer" sounds like a 1980s-era relic -- picture "War Games," where a young hacker mistakenly breaks into a government supercomputer and nearly sets off a nuclear battle with Russia -- but these massive systems are enjoying a popularity surge. Supercomputer sales rose 30% in 2012 from the year earlier, according to IDC.

Cray (CRAY), one of the market's pioneers, is riding the boom. It did $420 million in revenue last year, up 78% from 2011, and is targeting sales of $500 million for 2013.

Related story: What it's like to play with a supercomputer

"Ten years ago, [supercomputer makers] were trying to build systems that maybe 100 people around the world would use," said Barry Bolding, Cray's vice president of storage and data management marketing.

Back then, the market was almost entirely government, aerospace and automotive clients. As Bolding puts it: "They were wanting to simulate the Big Bang or model nuclear explosions or do things the government doesn't want to tell us about."

Now, companies like Procter & Gamble (PG) and PayPal are buying their own supercomputers.

"They have problems that are more complicated, but also because it's become a lot more affordable," IDC's Conway said.

Unlike its larger cousin, the XC30-AC can be cooled using air conditioners instead of a liquid cooling system, which requires special construction. It can also be connected to 208 volt power, rather than 480. Both changes make it much easier for businesses to install, Conway said.

The projects best suited to supercomputers are those that require thousands of processors working together to tackle a complicated task, like predicting a lava flow or simulating air flow over a jet wing.

That points to a fundamental difference between cloud computing and supercomputing. Clouds are typically built using low-cost, commodity hardware. That's fine for transactional work, where many transactions are happening at the same time but don't affect each other. If one fails because a component breaks, the program just tries it again.

That's not possible with the kinds of projects that supercomputers tackle. Their workloads are interconnected, and if one piece goes awry, the entire calculation -- which might take weeks or months -- has to start over. Supercomputers are also commonly used for calculations that must be completed very quickly.

PayPal, for example, needed a way to detect fraud before credit cards were hit with the charges. With its previous systems, the company often wasn't able to discover bad transactions until as long as two weeks after they happened.

In 2011, it built a supercomputer platform do real-time analytics on transactional data, using a system from Cray competitor Silicon Graphics International (SGI). IDC estimates that PayPal recorded $710 million in revenue savings in the first year after it started using the supercomputer, although Arno Kolster, a senior database engineer at eBay, said it's difficult to quantify since the company uses a number of different fraud systems. EBay (EBAY) is PayPal's parent company.

PayPal is now working on a new project using supercomputers to improve its detection of technical problems and reduce downtime on the site, Kolster said.

Swift Engineering, a designer of racecars, invested several years ago in a Cray CX1000 -- an earlier model also aimed at the mid-range market. The computer lets Swift test the aerodynamics of new models and make changes far more quickly than when it used to make physical models and test them in a wind tunnel.

"The challenge with computational fluid dynamics is there's so much data," said Clayton Triggs, business development manager at Swift.

The computer programs lays out a grid with millions of cells around the image of the car. A 20 second maneuver, then, generates a huge amount of data. With the supercomputer, "we're able to make modifications dynamically, which is important when you're trying to understand aerodynamics and improve the product," Triggs said.

IDC's Conway expects cheaper options like the XC30-AC to lure even more first-time buyers like Swift into the market. That's where the customers are right now, he says: "They're coming up from the commercial marketplace that never used supercomputers before."