Treasury Secretary Jack Lew just put a rush on looming fiscal fights this fall.

Lew said Monday that Congress must raise the country's debt ceiling before mid-October, which is when Treasury estimates it will have exhausted the extraordinary measures it has taken to keep a U.S. default at bay.

That new deadline is at least a month earlier than outside observers had been assuming.

Treasury's forecasts may change based on several variables, including tax receipts.

But a mid-October deadline means the debt ceiling negotiations are likely to run square into the fight over federal funding for 2014. To avoid a government shutdown, lawmakers must pass something by Sept. 30.

Problem is the two parties can't agree on a level of spending going forward, and there is disagreement even among Republicans as well. Plus, there's no consensus over whether to preserve or replace the automatic spending cuts that went into effect this year and will deepen next year.

Experts still expect that deals can be struck by key deadlines, but that's hardly guaranteed as no one can confidently predict the end games -- particularly on the debt ceiling.

What's the first thing lawmakers must do? Fund the government past Sept. 30, which marks the last day of fiscal year 2013.

Given the serious differences between the House and Senate on spending, there's no chance they will pass a real budget for fiscal year 2014.

So lawmakers will at least have to pass a temporary funding bill known as a "continuing resolution," or CR, before Oct. 1.

And if it's very short term, Congress will have to pass another one -- or several -- before Dec. 31.

Are they likely to pass a funding bill? Probably, but a lot could complicate the effort.

Normally when Congress passes a CR, it does so at current spending levels. Think of it like this: We can't agree on what to do, so let's keep on keepin' on until we can agree.

But that would be risky this time around because the law calls for lower spending caps to take effect in fiscal year 2014.

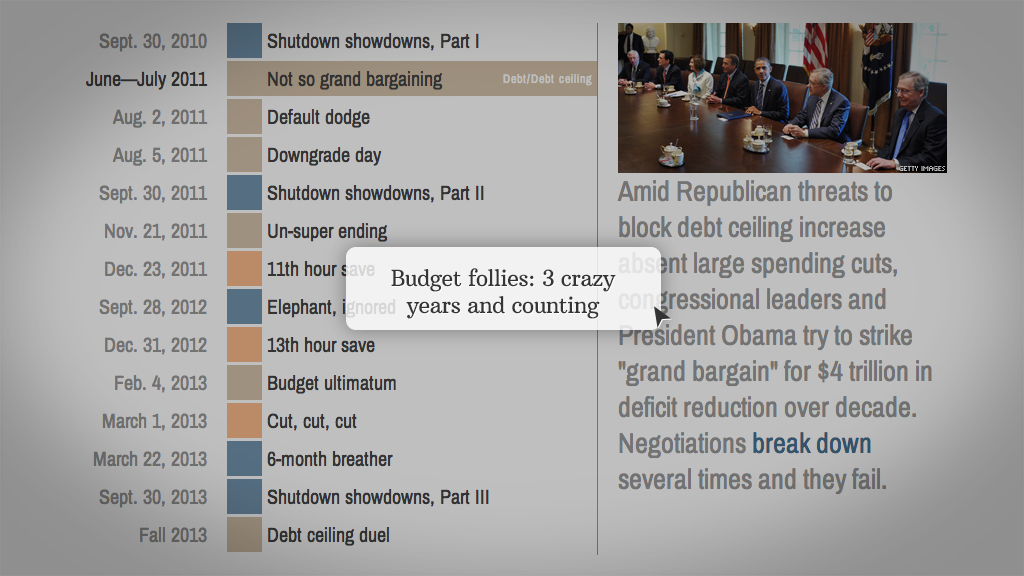

Related: Budget follies: 3 crazy years and counting

So approving temporary funding at this year's higher level means federal agencies would need to make abrupt cuts later to stay under the caps. By law, those cuts would need to occur 15 days after Congress adjourns for 2013 in a process known as sequestration.

Right now, Democrats and Republicans can't even agree on whether to keep those spending caps in place. And some conservative Republicans have threatened to vote against any funding bill that includes money for Obamacare.

What happens if Congress doesn't pass funding by Oct. 1? Much of the federal government will shut down.

What does a government shutdown mean? Hundreds of thousands of federal workers would be furloughed without pay. And most federal government offices, programs, museums and parks would be shuttered.

There would be exceptions, however.

Essential services that protect human life and property would continue to operate. That includes air traffic control, national security, the handling of hazardous waste, food inspections and disaster assistance.

Federal employees needed to preserve "essential" elements of the money and banking systems would not be furloughed. Mail would still be delivered.

And President Obama and Congress would keep coming to work.

What's more, an analysis by the Congressional Research Service concludes that the implementation of Obamacare is also likely to continue in the event of a shutdown.

How long would a shutdown last? As long as it takes Congress to agree on spending levels and pass bills that fund agencies at those levels. The longest shutdown lasted 21 days starting at the end of 1995.

Is a shutdown the worst that can happen? Sadly, no. The ramifications of not raising the country's debt ceiling in time would be much worse.

The country's legal borrowing limit is currently set at $16.699 trillion.

That level was reached in mid-May. And the Treasury Department began its official juggling act, employing "extraordinary measures" to keep the country from breaching the ceiling. But Treasury doesn't expect those measures to last beyond the middle of October.

Why does it need to be raised at all? Both parties in Congress have approved permanent tax cuts and spending increases over the years.

By doing so, they add to future deficits and increase the country's borrowing needs. Raising the ceiling simply lets Treasury continue to pay all the country's obligations that Congress has already approved -- whether it's a payment to a federal contractor, a Social Security check to a senior, or interest on the debt to a bond investor.

What's more, the aging population means there will be more spending on Medicare and Social Security with each passing year.

That's why raising the debt ceiling is not a "license to spend more," as some Republicans assert. And it's why the debt ceiling always needs to be raised periodically. Over the past two decades, it's been raised about 15 times.

What happens if the debt ceiling isn't raised? Uncle Sam would still have revenue coming in to pay for government services and agencies. Just not enough to pay for everything. And the longer the debt ceiling crisis lasts, the harder it would be to keep government operations running.

"After two weeks you'd have absolute paralysis," said Steve Bell, economic policy director at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

More problematic: The country could no longer pay all of its bills in full and on time. Treasury then would have to make legally murky decisions about who to pay and who to stiff.

Even if bond investors continue to be paid on time, the country could still be perceived as in default if it fails to pay its other legal obligations.

And if the full faith and credit of the United States is called into question, that could be disastrous for markets and interest rates -- which would harm the U.S. economy and Americans' financial well being.